Gamble Road by Penn Javdan

Gamble Road

by Penn Javdan

His boots sunk into grass fuzzing over bones mashed by mud that had formed into mounds of peat and after morning rain the peat rose with mist into his nose as petrichor. The scent of rain on dry earth and the scent of dust after the world had gone wet. Two boots encrusted by clumps of clay at his heels. Two boots angled at a doorknob before a final pivot to open the door.

Hunter worked defects north of the shoulders. The jaw. The mouth and tongue. The neck and by now the contours of the skull. Slicing through coal diggers crushed by crumbling rock and factory men deformed by the steam press. Before that morning’s procedure he stared at the sonogram glued to the wall of his operating lodge. A fog of miniature limbs. That morning his child would have been one year young.

The lights in the room blackened before he could screw the face shut. He struck a match and the flame flickered before The Great Slave Lake in Yellowknife. One year ago he’d lived two thousand four hundred forty seven kilometres south of that lake. South on British Columbia’s shores and clear of the jagged shield splitting the nation in two. Clear of whistling winds and albino wolves. Of scarves of emerald stars dusted in clusters across the sky. Twenty four hour stretches of twilight.

Arriving by motorcycle in this arctic was futile. But it was summer now and cottontip plant stocks stood waving. The lights switched on again and Hunter saw the reason standing. Watching.

&&&

“Your face healed nicely,” a voice said.

Hunter ran the back of his wrist against the scar above his beard. The one he’d sprouted to cover the scar but failed to cover. A shrivelled tapeworm ridging from under the right eye to the crease of his lips.

“This is a clean environment,” Hunter said.

“Well hello to you too brother.”

Watching Hunter sew the last gash the brother lit a paperroll and ashed the embers to the floor. He led Hunter out of the lodge to a motorcycle and a boy sitting on the saddle.

“Get off,” the brother told the boy.

Hunter went to the boy and unsaddled him onto his feet. The brother unsheathed a footlong blade from his hip and peppered crushed glass against the blade and massaged tobacco fibres into the glass before sniffing it. He sniffed it. The brother looked like his blue eyed son the boy and Hunter did not want to look at the brother’s face in the boy’s. Hunter watched the boy hug his colouring book. The boy looked up at Hunter and Hunter down at the boy.

“Take him,” the brother said.

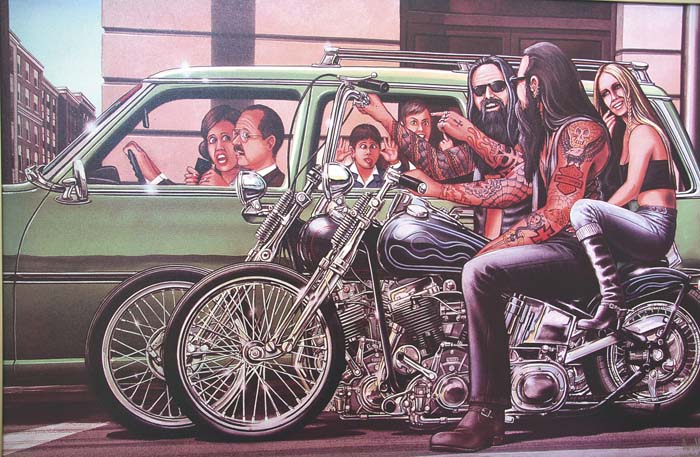

Letting the boy go the brother grinned and rubbed the back of his hands. Ink drenched and blue as berries. On the left in electric white an outline of a scorpion tail and on the right the scorpion torso and head completing the image. Ink belonging to a league of cutthroats and smugglers. For riding with the sting of night against poisoned mitts glowing in the outer dark.

The brother forbade Hunter any words. Already mounted the brother’s back faced Hunter and the boy. His spine covered in cracked hide and patched in the same emblem borne by those hands. He hammered his heel on the pedal and turned the throttle and rode two thousand four hundred forty seven kilometres back south of that lake.

Hunter led the boy to the cabin. Then went next door to the lodge to sharpen his knives and slipped them under his bed.

&&&

Hunter went to see the woman. On the way clots lumped in his veins as his history was still with him since all history came blood-soaked in the economy of pain passed down to honest men and the sons of honest men. Across the lake he stood in her home as she tightened the belt on her robe.

“Let me tell you the boy’s name,” he told her.

The woman shook her head. The scar on her belly twinned the scar on his cheek. Three inches to the left and she would have died like their child had died while in her belly and died with it on the rear of Hunter’s motorcycle riding for his brother.

“Let’s start over,” he said.

Once more she shook her wet head dripping from the shower while glistening like she had glistened freckle faced and pink-lipped in the mornings on Hunter’s side of the lake.

“You can’t choose who you get to be,” she said. “Not anymore.”

Draped over her chair was a ranger coat talking out of its pockets. Radio static until beyond muddy tones a voice dispatched for the brother’s arrest. Over the coat’s shoulder the woman’s nightgown laid laced in silk-thread twists at the breast cups.

Hunter left her in her robe as the radio continued spitting into the room.

&&&

The boy tried to eat the pancakes Hunter had sugar dusted the way he knew the boy liked and tried colouring the colouring book within the shoots of timber huddling around the cabin. But the boy could not eat or colour. The brother and his motorcycle were idling in front of the cabin as Hunter arrived at the doorstep. The boy’s belongings crammed in the saddlebags and he propped on the rear seat behind his father. Behind the shoulder slung shotgun shaved down at its butt to fit peacefully into the palm.

“Change of plans,” the brother said. “Kid’s going back to BC.”

Hunter watched his brother ride the boy away. This time he followed.

&&&

Far enough and only when far enough could the naked eye see the cabin perched on the cliff as golden beak hawks suspended overhead, branch-hanging from thousand year old pines, waiting, waiting.

Mint. The walls were mint coloured. It soothed Hunter’s brother’s men. He carved them new faces. The men wouldn’t know what they’d look like until after they’d look like it. One after the other. Folds of skin pronounced in slopes and grooves so the ranger and all rangers would conclude them vanished or killed.

The boy sat outside Hunter’s door. He peeked through the window and watched tubes funnel liquids to blobs unconscious on their spines. He surveyed Hunter’s face as if knowing you had to see the light in someone’s eyes to trust them. The boy saw Hunter’s shimmer in their deposits of amber. Their stillness.

When Hunter finished then the boy approached and peeled his sleeve high and there the bruising blotted in maroon fades on his arm. Hunter paused.

“Hold on a little longer,” he told the boy.

Hunter sent the woman a picture of the bruises and of his face and failing smile. When Hunter spoke of the woman the boy spoke as if a child curling its tongue for the first time. “I don’t want to go alone,” is what he said.

“You won’t,” Hunter said.

The woman replied to Hunter without a yes or a no. Instead with an address.

&&&

After stripping Hunter’s license the ranger flirted with speeches of flying him to the penitentiary.

Your brother’s going down, the ranger said. Help me put him away, the ranger said. You’ll walk. Just leave me and my woman alone. With the ranger gone Hunter thought about taking the boy with him and just the two of them alone. Somewhere as strangers to the world. Hunter began packing. Folding shirts and socks and pyjamas and the boy’s colouring book and then freezing before zipping the zipper.

The brother appeared at the door.

“No,” Hunter said.

“Give me a new face.”

“No,” he repeated.

The brother tore the colouring book and let it fall and left. Hunter continued packing.

&&&

They let him apply his own painkiller. A needle to the rear before his brother dislodged the knee joints splitting them open. Hunter did not scream. He did not budge. He fixed his eyes on his brother as his brother wiped it then returned the blade to one of the shipping containers the ranger had been spying on. An aim to raid the racket. The ranger thought he was going call the woman and tell her it would all be over soon. One brother in wrist-cuffs and the other on a plane to whereverland.

&&&

Hunter agreed to give his brother another face. He healed himself to his feet with gauze wrapped around his kneecaps like a leg turban. He hobbled to the operating room. His brother was already on the table. Hunter pumped sleep through the veins and the body fell still. He lifted the incision blade. He stared at the unconscious lump of flesh that was his flesh and blood. He stared at the blade. He looked back at the lump. The solution was in his hands. He stopped. He waited. The boy arrived and Hunter let him in the room.

“Ready?” Hunter said, resting his hand on the boy’s head.

The procedure lasted ten hours. When the brother awoke a mirror was facing him. His face looked exactly as it had before he was put to sleep. The boy’s face did not.

&&&

The woman collected the boy from the Yellowknife Airport. She took his hand but he pulled away.

“He promised,” the boy told her.

“He’ll be here, sweetheart.”

But Hunter did not answer the phone. The woman took the boy and they walked out hand in hand.

&&&

Hunter had morphed into a well of puss and bubble. Infections from wounds and the aftermath of wounds. Abscesses. Gangrene. Sepsis. The Self. Beneath the buzzards in British Columbia he carried forward a ruined face to confront in the mirror. Swatches of fog swirled thick and dim and blinded all exits leaving sound untouched. Grapefruit hues began bleeding over the rim of the Pacific. From the orphan mouthed road mufflers purred then narrowed near the cabin until bordering the base the rumble unknotted the straw braids entangled in the welcome mat pasted to the porch.

Hunter listened to the motorcade. No gifted hands remained nor any sanitized tools nor any specimens to fashion and incise. Clouds drifted through the mountain peaks as if to clear away all things that had existed before them, erasing every human artifact, each foot sunken crater and fingerprint greased upon the earth.

Outside a clopping slanted its way up the stairs with the heavy heel he’d heard before. The front door whined open as Hunter stayed facing the mirror. He smiled at his reflection. He nodded at himself.

The only person whose identity he could not alter was his own.

* * * * THE END * * * *

Copyright Penn Javdan 2015