Baked Earth by Steve Carr

Baked Earth by Steve Carr

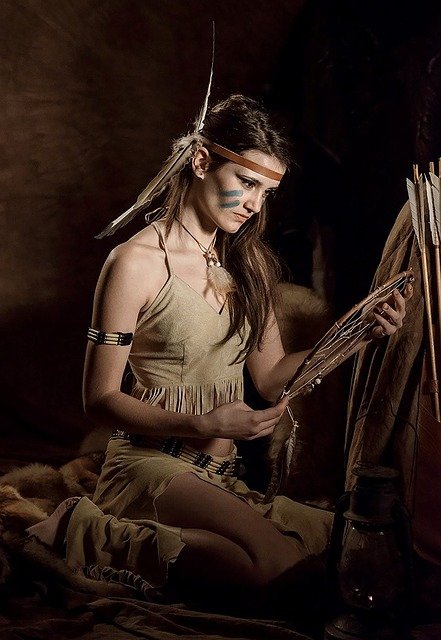

The earth was baked by the intense rays of the summer sun. The thudding of the horses hooves on the hard ground as the soldiers rode through the outpost made the floor of the cabin vibrate. Wearing the thinly tanned deer-hide moccasins worn by a young Sioux Indian girl, raped and murdered by six fur traders less than fifty miles from the outpost, Amanda felt the shudder of the vibrations through the soles of her feet. The moccasins were similar to the ones she wore for the ten years she lived with the Sioux tribe. She was only sixteen when captured and taken to the Sioux camp after the murder of her parents and two brothers by a Sioux war party as they were crossing the plain in a covered wagon. For the next year she was passed from one Sioux brave to the next until she was taken in by Rushing Wind as his third wife. By then she was so traumatized that she lost all memory of anything that preceded her capture. Who she had been and where she came from, she had no idea.

She was brought to the outpost the year before as Fallen Dove and given the white man’s name Amanda.

The door to the cabin opened just as the last of the soldiers rode by leaving a cloud of dust in their wake. Amanda turned from the small window from where she had been watching them and saw her husband, Jackson Riley, walk in. She realized that while being lost in thought, time had gotten away from her and that she had forgotten to add salt to the pot of stew she had placed on the stove. He hung his hat on the hook in the wall by the door, glanced at her, his face sunburned, and went to the bucket of creek water she had brought in earlier in the day. “It’s hot as hell today,” he said and then scooped out a dipper full of water and poured it over his head. He shook the dripping water from his beard. “That foal born last night didn’t make it.”

“That’s too bad.” she said as she crossed the room to the stove and grabbed the tin of salt from the shelf above it. “How’s the mare doing?”

“A bit tuckered out, but fine,” he said.

“That’s a blessing at least.”

Amanda had a child, a boy, soon after joining Rushing Wind’s longhouse, but suffered several miscarriages after that and then never conceived again. It was the child, Running Elk, she was thinking about. He was still an infant when the soldiers had forced her onto one of their horses as while she was out gathering berries and brought her to the outpost. For the first year after being brought to the outpost they had kept her ankle chained to a post in the floor in a room at the soldier’s barracks to keep her from running away. Slowly re-introduced to the white man’s ways of talking and thinking by the women of the outpost, she gave up thoughts of returning to the Sioux tribe, knowing they would kill her on-sight. She was married to Jackson, the outpost’s livery stable owner, initially not out of love, but because the other women demanded it.

“We can’t have a Sioux whore, even if she is white, going about this outpost unmarried,” they said.

She unscrewed the lid from the tin of salt and poured a palm full into the pot and stirred the boiling stew. “The soldiers have been back and forth a few times today,” she said. “Are the Sioux on the warpath again?”

“There’s rumors of secession,” he said. He sat at the table and watched as she ladled stew into a bowl and placed it in front of him.”

“Secession? What’s that?”

He put a spoonful of stew in his mouth. “The southern states are threatening to break away from the north. There’s talk of war,” he said. “It has thrown the local garrison into turmoil since there are men in it from both the North and South. Colonel Matthews is doing everything he can to keep this outpost from being torn apart.”

She sat at the table. “What does it mean for the Dakotas?”

“Not much,” he said, “The Sioux will continue killing settlers and we’ll continue to kill the Sioux.”

She put a spoonful of stew in her mouth and coughed. Too much salt. She hadn’t forgotten to put in the salt earlier after all.

“A small wagon train that has stopped on the border of the outpost brought with them a young Sioux male that tried to steal a horse from them” he said. “They had him trussed up like a pig ready for slaughter. They handed him over to the soldiers.”

She rose from the table and took their cups to the water bucket. “If he’s young, I hope they go easy on him.”

“They hang horse thieves, no matter what the age, and especially Sioux horse thieves. You can’t teach a Sioux savage right from wrong.” He glanced at her seeing that her back had stiffened. “You were never actually a Sioux,” he added contritely.

She scooped the cups into the water, filling them, and brought them back to the table. She placed his in front of him. “Strange that he was all by himself,” she said.

He took a large swig of the water and then wiped dribbled water from his beard. “Stranger still is that the word going around is that the boy has blonde hair and blue eyes but has Sioux facial features and skin coloring. A half-breed, no doubt.”

Shocked, she accidentally knocked over her cup of water onto the floor. As she bent down to pick it up her blonde hair fell across her face.

&&&

Just past sunrise, before Jackson was due to get out of bed, Amanda carried the water bucket out of the cabin, walked past the well, and headed for the creek. Getting water from a creek was one of the last holdovers from her time with the Sioux, something she did out of habit. Rapid Creek wound its way between the narrow grassy banks on the edge of the outpost. In normal weather its deep water rushed along and was cold, but the summer’s extremely hot weather had turned it warm and and it ran slowly, as if it suffered the same lethargy brought on by the heat that affected the citizens of the outpost. She was the only person at the creek when she dipped the bucket into the water. When going to the creek in the morning she never wore shoes, and as the bucket filled, she placed her feet, one at a time, in the water and splashed them about. The times she had taken baths in the creek, even with all her clothes on, had so outraged the other women in the outpost, that she stopped doing it, but she longed to immerse her body in the creek. With her feet washed and the bucket full she walked back to the cabin in time to see a dozen soldiers on horseback on the road in front of her cabin heading eastward, toward the plains beyond the outpost. She placed the bucket at the door and swiftly walked toward the barracks.

At the eastern side of the barracks she heard soldiers inside talking and laughing, their words garbled, but it left no doubt in her mind that they were taunting someone. She made her way to the side of the barracks to a window in the room where she had been held, and peered through the bars. The blonde haired Sioux teen was chained to the post in the middle of the room. Four soldiers were in the room with him. They repeatedly kicked and slapped the boy seeming to try to elicit a response from the youth. But he remained sitting on the floor, neither looking at the soldiers, or looking at anything in particular. He had his head held high and stared straight ahead, his eyes fixed on something only he saw. The boy’s deerskin jacket had been removed from him and lay crumpled in a corner. On his jacket lay his headband with a single hawk’s feather sticking out of it and a pile of blonde hair that the soldiers had cut from his head. She knew without a doubt that the boy was Running Elk.

Ten minutes later she picked up the water bucket and went into her cabin. Jackson was seated at the table, still in his long johns. Although still hot, the morning temperature inside the cabin was better than that outdoors.

“Where have you been?” he growled.

She lifted the bucket. “I went to get water, as I always do.”

“You were gone longer than usual.”

“I stopped to watch soldiers leaving the outpost,” she said. “It looked like they were planning on a skirmish with the Sioux.”

“There’s always a skirmish with the Sioux. Could you get busy making my breakfast? I’ve already lit the fire in the stove.”

“Certainly.”

She poured water from the bucket into a coffee pot, added coffee, and placed it on the stove. She then slipped on the moccasins and began making biscuits.

&&&

Mrs. Cavendish at the dry goods store scooped flour from a large barrel and emptied it into the feedsack that Amanda held open. The store was busy, with other women from the outpost, other merchants, cowboys, folks from the wagon train, and a few soldiers going in and out. The wooden blades of a fan that hung from the ceiling slowly circled about, doing nothing to cool the store. While having her sack filled with flour, Amanda stared at the fan, trying to imagine what made it work. The string that hung from it had something to do with it, but she couldn’t make the connection between the string and the whirling blades. It was the most modern contraption in the outpost, not counting the newest carbine rifles.

“Sugar also?” Mrs. Cavendish said after loudly clearing her throat. She was short, stout and her cheeks were the color of a ripened tomato.

Amanda realized that the store owner had been talking to her, and from the impatient expression on the woman’s face she had been asked the question at least a couple of times.

“Not today,” Amanda said. “Do you have any peppermints?”

Mrs. Cavendish eyed her curiously. “Peppermints? Has Jackson acquired a sweet tooth?”

“They’re for me. I was having a hankering for them.”

“I have a small tin of them in the back that I haven’t gotten around to sitting out yet. Give me a minute and I’ll go get them.” She handed the sack to Amanda and disappeared through a doorway draped with a burlap curtain that led to the storeroom.”

Amanda carried the sack over to the cash register and set it up on the counter. From behind the counter, Mr. Cavendish – as thin and pale as his wife was portly and full of color – was engaged in a conversation with one of the cowboys from the wagon train who was rolling a cigarette. The cowboy’s hat was pushed back on his head, revealing thick red hair.

“We chased that boy about a mile before catching up with him,” the cowboy said. “He put up a heck of a fight before we were able to tie him up.”

“Awfully strange that a Sioux youngster that age would be all alone out there,” Mr. Cavendish said.

“He only speaks that Indian gibberish so we couldn’t understand a word he said so no one knows what he was doing, other than trying to steal a horse.”

“Lakota,” Amanda said.

The two men looked at her.

“What?” the cowboy said.

“The Sioux speak Lakota.”

Mr. Cavendish rolled his eyes. “Give a woman a little bit of knowledge and she thinks she knows everything.”

The cowboy laughed.

Mrs. Cavendish came out of the storeroom and placed the tin of peppermints on the counter. “How many of these do you want?” she said to Amanda.

“Just a handful,” she said, “and give me a bottle of whiskey.”

Minutes later, Amanda left the store carrying the sack of flour, a bottle of whiskey. She had put the peppermints in the pocket of her skirt.

&&&

Amanda filled a cup with whiskey, handed it to Jackson and encouraged him to drink it all. Sitting on the bed he stared at the whiskey.

“You know I haven’t the tolerance for such a large amount,” he said. “I ain’t a drinking man. Why’d you buy it?”

“In this heat that you been working in I thought it would help you sleep,” she said. She bent down and pulled his boots off. “There, now you can drink the whiskey and lay back and close your eyes and sleep until morning.

He tilted his head back and poured the entire cup in his mouth, gulping it down. He wiped dripping whiskey from his mouth and beard with the back of his hand. Feeling the immediate effect of having chugged down the alcohol, he shook his head, handed the empty cup to Amanda, and then laid back. Within minutes he was sound asleep and snoring loudly.

Amanda reached into her pocket to make sure that the peppermints hadn’t fallen out, and then quietly left the cabin. The darkness of night did nothing to quell the heat. From the far end of the outpost the raucous laughter and hollering of the cowboys and soldiers could be heard coming from the saloon. The street was empty of any of the citizens of the outpost. She hurriedly walked to the barracks, and not seeing a sentry standing at its front doors, she made her way to the window of the room where Running Elk was being held. The boy sat on the floor, his legs crossed, the chain still attached to his ankle. He was illuminated by the faint glow of an oil lamp.

“Running Elk,” she whispered in Lakota Sioux language.

He looked up, blinking several times before his eyes adjusted to seeing her in the darkness. “Who is it who calls me?” he said.

Amanda recalled so little of the Sioux language, having not spoken it in years, that she didn’t understand what he said, but by the inflection in his words, she knew it was a question. She took a peppermint from her pocket, reached through the bars, and tossed it to him. It landed at his feet where he stared at it for a moment before picking it up. He sniffed it first, and then placed it in his mouth. A smile quickly spread across his face. She then tossed him the remaining six pieces, one at a time, and watched as he put each one in his mouth. With his mouth filled with the candy he kept his eyes glued on her.

“I’ll be back tomorrow,” she said, aware that he didn’t understand the white man’s language, but she hoped the gentleness in her voice would comfort him. She turned away from the window and made it back to the street.

“What are you doing?” It was a man’s voice, harsh and commanding.

She whirled about to see a soldier standing outside the door of the barracks. There were sergeant stripes on his unbuttoned shirt. He wasn’t armed, but he wore a belt with a knife tucked into it.

“Just taking a walk,” she said. “It’s such a hot night.”

He walked towards her. “All night’s are hot, lately.” Nearing her and able to glimpse her better in the ambient light of night, he said, “You’re kinda pretty. Don’t you have a husband to keep you indoors at night?”

“My husband is at the wagon train, helping them prepare to continue on with their journey.”

The sergeant stepped up to her and scanned her face. “I know you. You’re Jackson Riley’s wife. Yeah, I know all about you. You were once an Indian squaw.” He placed his hand on her shoulder and squeezed it. “What’s wrong missy, doesn’t Jackson satisfy you the way those Sioux savages did?”

She pulled away. “Please don’t,” she said. She half turned to walk away but was grabbed by the sergeant and pulled to him. Instinctively, a natural reflex borne from experiences she had shut out of her mind, she pulled the knife from his belt and plunged it into his neck. As blood spurted from the wound he stood absolutely still for a moment, his eyes bulging, and then collapsed onto the hard earth. His body convulsed for a second and then he died. She ran from the site, reaching the front door of her cabin just as bolts of lightning spread like tentacles across the sky above the distant plains. She went inside, washed the blood from her hands and then undressed and got into bed next to Jackson.

&&&

The next morning she was awoken by the sounds of hammering. Jackson was still asleep. She got out of bed, put on her dress, and went outside the cabin. In the early morning light she could see that soldiers were building gallows in the street in front of the barracks. The noose hadn’t been hung from the crossbeam yet, but she had seen a few hangings of horse thieves and Sioux warriors since being brought to the outpost. The purpose of the scaffolding was unmistakable.

On the way to their store, Mr. and Mrs. Cavendish stopped, each standing on either side of her.

“Isn’t it awful that the boy murdered that kind Sergeant Filmore?” Mrs. Cavendish said.

“The Sioux boy that they have in chains murdered the sergeant?” Amanda said, unable to disguise her astonishment.

“He got away long enough to kill the sergeant, but they recaptured him,” Mrs. Cavendish replied as if it was an indisputable fact. “Reverend Lott stopped by first thing this morning to tell us all about it.”

“The boy will be hanged first thing tomorrow morning,” Mr. Cavendish said. “There won’t be any peace until they’re all driven from the plains or hanged just like the savage we’re holding.”

“He’s just a boy. He has a mother and father who are probably concerned about him.”

“They raised a horse thief and a murderer,” Mrs. Cavendish said haughtily and then walked on, followed by her husband.

Thirty minutes later, Amanda stood at the stove, holding the coffee pot. She was eyeing her husband, waiting for him to respond.

Jackson sat quietly for several moments staring at the cup of coffee on the table in front of him. “I understand why you never told me about having a child,” he said at last as if expelling air he had held in his lungs for too long.

“I never thought I’d have to tell you, or anyone, about it – him – but I told you now for a reason.”

“What reason is that?”

“I need help getting him out of the barracks and out of this outpost.”

&&&

It was a little past midnight when Jackson approached the two corporals standing as sentries outside the front doors of the barracks. He knew them both, Jessie was from Alabama and Henry was from New York. They were young hotheads who frequently got into scraps with each other, escalated by their opposite views on slavery. Jackson had in hand an opened full bottle of whiskey. Waving the bottle he staggered toward them. “You boys look mighty thirsty,” he slurred.

“It’s mighty hot out here and I sure could use a drink to wet my whistle, but we’re on duty, Mr. Riley,” Henry said.

“Not as hot as back home on the plantation and watching the Negros picking cotton,” Jessie said.

The corporals scowled at one another, set their rifles against the door frame, and accepted the bottle, passing it back and forth while bickering about slavery. With Jackson’s encouragement they drank the entire bottle. When they were near falling-down drunk, Jackson said, “If war breaks out which side will win?”

“The South,” Jesse said.

“The North,” said Henry.

This led to blows, and then them wrestling in the dirt, each one haphazardly landing punches.

It was then that Amanda appeared from out of the darkness, went into the barracks, stealthily walked past the rooms of sleeping soldiers and made her way to the room where Running Elk was being held. Seeing there was no sentry at the door she took the ring of keys from the hook in the wall, unlocked the door, and went in.

Leaning against the post, asleep, Running Elk raised his head, opened his eyes, and smiled at her.

She knelt down beside him and whispered his name. She touched her hair and then touched hers, and repeated this several times. She couldn’t recall the Sioux word for mother, but she could see in his eyes that while he may not have remembered who she was, he understood there was a bond between them and she was there to help him. He watched quietly as she unlocked the chain around his ankle. He put on his jacket and headband and then followed her out the door. Outside, the corporals were stretched out on the baked earth, both passed out. Amanda, Running Elk and Jackson ran to the livery stable where Jackson had spent the day stocking a horse-drawn wagon with enough supplies to get them across the plains going west. With Running Elk hidden under burlap sacks, they rode from the stable and out of the outpost without being stopped. The sentries were only concerned with who was trying to get into the outpost, not with who was leaving it.

Hours later, having driven the wagon as fast as the horses could run for extended periods of time, they stopped at sunrise on the road that cut a swath through the broad expanse of sun-baked prairie grass just as rain began to fall from the sky as if poured from a bucket.

There, Running Elk reached out and stroked Amanda’s hair and then climbed down from the wagon. He exchanged a last smile with his mother before turning and running southward toward where his tribe was said to be located. He didn’t look back.

They watched him until he was hidden by a veil of rain, and then began their trek to Oregon.

THE END

Copyright Steve Carr 2020