Eternal Flame 1933 by Douglas Kolacki

Eternal Flame 1933 by Douglas Kolacki

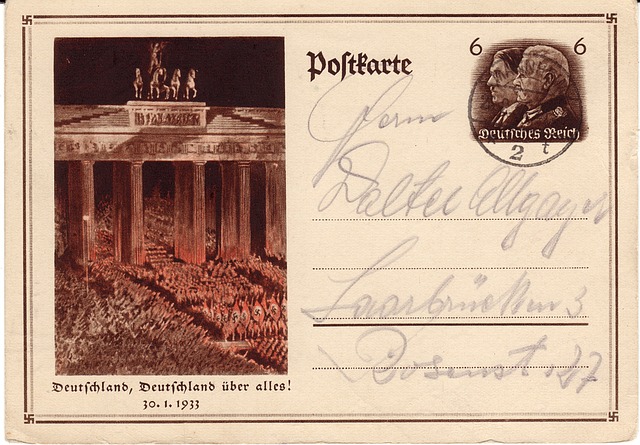

May 10, 1933

The Bebelplatz lit up Berlin. The heat of fire and national fervor combined to sizzle the light rain before it touched the ground. Forty thousand students massed around a flaming stack of crossed logs, and into this flew the books–books brought in cars, passed from hand to hand or carried in armfuls by running students, catching fire or carpeting the ground around the central blaze. The people chanted, right arms raised, while a flag-draped podium with a microphone stood ready for Reich Minister Goebbels to address the crowd by the light of twenty-five thousand pieces of burning literature.

The voices thundered as one: “Against class warfare and materialism. For the community of the Volk and an idealistic way of life!”

This was for Marx–anything by Marx, flung now into the roaring volcano, to finish the work begun by the party in expelling Communists.

Storm Detachment Private Julius, rigid in precise rank with his comrades in brown shirts, gleaming belt buckles, hooked-cross armbands and caps strapped tight under their chins, cried out: “Against soul-shredding over-emphasis on sexual instincts. For the nobility of the human soul!”–Freud’s writings flew into the great mound, in addition to the copies already smoldering down inside of it.

Now Julius held up a novel surrendered by his father–the man who first told him about Adolf Hitler nine years ago this very day, after returning from a meeting with a glow Julius had not seen on any face before or since. Lately, however, worry clouded father’s eyes, so that Julius had to coax him to give up his much-prized first edition of All Quiet on the Western Front.

Hitler unleashed, was what worried father. Julius eavesdropped on his conversations. Originally, the Leader was surrounded by the cabinet and President Hindenburg, and they were to keep him under control, channel his fanaticism for Germany’s good. But the Reichstag fire set Hitler ablaze as well, propelled him to absolute dictatorship, and now who could tell him where to stop?

Father’s fear, spoken only when his son was out of the room: He’s going to get us into a war.

Arms snapped up on either side of Julius. Hastily he transferred the book to his left hand so he could join his comrades in their salute.

“Against the literary treason committed against the soldiers of the world war,” he shouted word-for-word with the rest. “For educating the nation in the spirit of military might!”‘

You’re wrong, Father. I wish you could see your worry is needless. Our might will protect us from war, if we but listen to and obey him! And he threw in the novel.

It was then that he noticed the other book burning across the square.

No chants. No shouts. And far fewer books, not yet alight; they were just getting started. Three of the participants held long black rods with flames dancing on the ends, making a slow, deliberate motion of touching them to the pile. For the second time that day, Julius watched a fire spread and lick up paper.

“The era–”

The voice crackled from speakers. He snapped his head about. A lank, glowering man with overlarge head and swept-back dark hair manned the podium–Reich Minister Goebbels, here to sanctify the event with his official presence.

“–of extreme Jewish intellectualism has come to an end. The German revolution has again opened the way for the true essence of being German.”

Julius snuck a glance at the other burning. Investigate it? Leaving now would be unthinkable. But curiosity won out and he stepped away, weaving through the mass of students, marching briskly across the square. Hopefully no one was watching him. Goebbels’ voice rang from the speakers, seeming to accuse him–he thrust it from his mind. This wouldn’t take more than two minutes.

The smaller gathering’s dozen citizens managed to represent the whole national population. There was a college-aged young man, like all the students here tonight; a white-haired old fellow with a stoop, who reminded Julius of the grandfather who showed him how to make paper airplanes when he was little; a woman in a blue trim dress, who brought secretaries for high officials to mind. Their campfire burned not so fiercely as the conflagration in the center, but it churned up a grayish-white storm of smoke that scattered flakes of blackened pages across the square, to mingle with those of its roaring relative now heating the square’s center too hot to touch, breathe, or tread upon without the heat stinging your feet through your shoes.

Several of them held books. The woman raised one over her head like she wanted everyone to see it. A Hemingway, perhaps? Or Einstein? Maybe she’d also scored an All Quiet. He was close enough now so that, if she held it still another moment, he could make out the cover.

He squinted. Then he jolted as if he’d touched a bare wire.

No. Wait. Is it–?

A half-burned title page fluttered by. Charred black, enough still remained to glimpse the word MY and, after that, STR.

Julius stared open-mouthed. Then he clenched his teeth and broke into a run.

Did they feel as his father did? But father would never do this! Julius needed him to be reassured, to tell his son Julius, you were right.

And these people weren’t helping!

The woman and the young man watched him approach. They both clutched copies of–no denying it now–the Leader’s own My Struggle. One, two others, held copies as well. And more lay atop the small bonfire, the flames licking at them, the Leader’s picture glaring out as if annoyed at this outrage. One such picture turned black and curled up, swallowed by the fire, as Julius ran up snorting and fuming and charging like a bull.

The offenders bolted. A teenaged boy not much younger than Julius straggled in the rear, throwing his copy of Struggle aside to splat open face-down on the pavement.

“Hey!” Arms and legs pumping, Julius touched the dagger that had belonged to his grandfather, and that his grandfather claimed wore the blood of sixteen French and British soldiers. Although he’d prefer his truncheon, the better to bash heads with.

The traitors darted into an alley. Julius leaped to avoid stepping on the discarded copy of Struggle, summoned a burst of speed and raced in after them, fists pumping

–and into the middle of a street

He cried out, staggered, flailed, caught his balance and stopped.

The alley was gone. He now stood on…Herman Göring Strasse? Yes, he knew this area. Used to. The Chancellery–yes, there it was. But–? This was ten-odd blocks from the Bebelplatz, where he’d been only seconds ago.

His knees wobbled. He glanced around, unbelieving. God in heaven! What had happened?

Berlin had been clean, orderly, with no destructive force save the fire. And the fire itself had been part of the order, tamed and controlled by the party, burning where the people decided it would burn, for how long it would burn, and what it would burn.

But now the flame had burst its bounds. Spreading to buildings, it had gutted and crumbled them down to charred ruins, the air hazy with smoke. And booms–distant artillery firing–a shell shrieked down and smashed into the pavement a block away, jarring him off balance. He swayed, staggered, but managed not to fall.

What on earth?

The rumble subsided after a moment, and he heard a tinkle off to his right. Something else had fallen to the rubble-strewn street. Thrown from a window? A framed photograph. The tinkle was the breaking of its glass. He staggered, bent over it. The Leader.

“What is happening?” He grabbed his head with both hands, he shouted, though he saw no one in all this apocalypse. He drew himself up, remembered his uniform and hooked-cross armband, the national symbols of pride, of might. But now it was only himself, alone, sweating and breathing smoke. His comrades, the party and the citizens–where were they?

“Are you all mad?”

His head swam. He shook it–focus, focus. Another shell exploded somewhere nearby, the ground shuddering under his boots. This was the Chancellery gardens, pulverized and torn up. He recognized it…but not the concrete structure a few steps away, crowned with some sort of tower.

Get under cover. He made for the structure, his boots kicking up loose dirt, skirting a crater and practically throwing himself against the structure’s wall.

It was now that he noticed the stairs leading down inside, and movement at the bottom. He hugged the wall, puffing for breath. He heard a door wrenching open, saw a bobble of heads and then men carrying something up, wrapped in a blanket.

Ah. Good. Finally someone to–he recognized one of them and jolted, going weak in the knees all over again.

Minister Goebbels?

Julius had seen him only minutes ago in the square, tall and triumphant, voice ringing. But this was a different Goebbels who looked thirty years older, haggard and ashen-faced, eyes hollow. Then came a man Julius did not recognize, and behind him someone in uniform staggering under a load wrapped in an army-gray field blanket. The bottom half of a body protruded from the blanket, black trousers and shoes. Another man followed carrying a second body, this one a woman in a dark dress, slung over his shoulder with legs dangling over his chest.

Julius gaped. None of the group noticed him, but hurried to an artillery crater and half-laid, half-dropped their bundles there. A blanket flap fell away from the first corpse and exposed a face. Only for a moment–the official darted in and covered it back up–but there was no mistaking it.

Julius’ eyes sprang wide. He screamed. Another shell hit somewhere nearby and drowned it out; the men gave no sign of hearing.

The group hefted cans of petrol and splashed the liquid over the deceased, moving the cans back and forth, the oily streams cascading to and fro, sparing no part of their Leader the petroleum bath. The men tossed their emptied cans aside with clunking sounds. The petrol came up to nearly the rim of the crater, its fumes stinking and watering Julius’ unbelieving eyes.

The ashen-faced Goebbels and the others stood back. Someone struck a match, moved forward, and tossed it onto the petrol swamp.

A great fwoosh sounded and a ball of flame mushroomed up, its heat stinging Julius’ skin. He cried out and covered his face. When he looked again, Goebbels and the others had retreated to the top of the stairs and stood in rank, raising their arms in the familiar salute. Then they scrambled back down, their immolated leader forgotten. Somewhere nearby, another shell struck.

Julius remained in place, trembling. He could not take his eyes from the flaming pyre. It burned with the fierceness of the hill of books he had just left behind, a few minutes and a thousand years ago.

And now other Germans appeared.

Julius watched, half in a dream. He recognized some of them, and it seemed like a year since he’d pursued them in the Bebelplatz. Among them were the three carrying the long, black sticks. They converged on the roaring bonfire that he still could not believe was devouring Adolf Hitler. Did they know who it was that the flames were reducing to ash?

The citizens made a half-circle around the pyre. More hurriedly than before, they extended their sticks. The ends caught fire. They withdrew their torches, turned and fled, weaving around the rubble strewn on the street, toward a light like a spotlight on the side of a half-demolished brick building. Julius watched numbly as they approached and kept going until the woman at the front dissolved into the light. The two other torch-bearers followed, then the white-haired elder and the lady in gray and the others, carrying copies of Struggle as well as Rosenberg’s Myth of the Twentieth Century and Houston Chamberlain’s Foundations of the Nineteenth Century. Others held pictures of the Leader. The procession continued until all were gone and only the light remained, a steady, clean glow unlike the yellow fires raging and pounding Berlin into ruin.

Julius remained still. Nothing could shock him anymore. All these impossible things, one after another, had overloaded and numbed his brain.

“A terrible sight, is it not?”

The voice came from beside him. Slowly he turned his head. A man with an angled face, brown hair silver at the temples, wearing a gray suit that reminded Julius of that field blanket and what it contained, and this brought a fresh stab of pain. His practiced eyes picked out the downward sloping nose, black eyes, a dead giveaway. He spoke the first thought that came to mind.

“You…you Jews…” He tried to spit the word out, but it caught. “Are you happy you got your way?”

The man’s eyes flared. “Is that what you think?”

“How did you do it so quickly?” Julius’ voice rose to shrill heights. “It’s not possible. You were even more dangerous than–”

“Stop that!” the man hissed between clenched teeth. “I’m not Jewish! I’m as German as you are, take my word for it. Did you come from Bebelplatz, the book-burning?”

“Yes.” Artillery boomed in the distance.

“You saw the fire, gave chase?”

“Yes, yes, what’s this all about?”

The man reached under his jacket, removed a black box slightly longer than a pack of cigarettes. Julius practically lived on cigarettes; the Storm Detachment even had their own brand. The box trailed two thin wires sticking out between the buttons on the man’s jacket.

He held out the device, arm up straight like the party salute. Julius guessed this was not intentional. “We–this–it controls a great secret we discovered only after the war. We come from a year after now, from 1946, and you from twelve years before. 1933, correct? And here we meet.”

He waited, as if expecting Julius to go into shock or something. The bombardment started up again; a shell shrieked down and exploded somewhere nearby. “And?” Julius cried out. The damn fool just stood there holding his ridiculous-looking box as if nothing at all was going on.

“We can travel to this day, and to the one you came from, the burning. Only those, and no others. And so some of us wanted to make a statement. We must start somewhere. Now listen: something happened that we didn’t expect. You arrived here minutes before we ourselves did from our own year. It’s likely others followed you, too, and may appear at all different times–some perhaps an hour ago, others an hour from now.”

“You Jews, you Jews!” Julius flung the word out. It was like a lifeline to the Germany he knew.

Another shell blasted somewhere nearby, dirt flying. The man flinched–Julius didn’t–and resumed, babbling now. “Goebbels is there. We have to alert him, bring him here, show him where his regime is going to lead. And you know how close he is with Hitler. If he saw this for himself…can you help?”

Jews, Julius thought.

“He was university-educated, unlike his dictator, and if that idiot hasn’t brainwashed you completely will you help us?”

Julius rocked in his boots as another shell crashed somewhere. I just saw Goebbels! He was here!

And then the meaning of “idiot” sank in. That did it. His hand sought his dagger, found it, pulled it from his belt.

Julius snarled and lunged. The man recoiled, surprise in his face, mouth opening but Julius swatted the side of his head and the weird box flew from his hands, the wires snapped and it spun end over end in a graceful arc, the two loose wires trailing behind it, landing on a patch of the Chancellery gardens grass that still remained. Nonetheless the box shattered.

Julius jammed his dagger in the traitor’s chest. The man’s face contorted and he collapsed, seeming to crumple as if all his bones were breaking and crumbling inside his skin. He lay still, a tangle of limbs with surprisingly little blood, the dagger buried to the hilt in his rib cage.

Julius gasped for breath. His heart raced. His mind swam and his stomach churned–no, he was defending Germany, remember that! The blasts came one after another now, his eyes sought the spotlight where the others vanished and he must have arrived. There–still there. It even shimmered around the edges, clearer now through the smoke. And it had grown in size. He could even make out the Bebelplatz and some of the throng through it.

Home! He ran for it.

A nearby explosion threw him off his feet, and he landed in a heap in the gardens. Dirt showered over him. Lying on his stomach, he looked up, hands clutching the earth.

The opening still remained. But the destruction of the box had set something in motion, for now it was expanding, growing to reveal the glorious Berlin behind it, the blazing mountain of books like a beacon and dark shapes of humanity gathered around it, the closest ones illuminated in flickering light. And still the doorway grew, large as a shop, then a house, then a hotel, the brick ruin behind it disappearing into an immense window to the city’s past.

And Julius, he watched as a tank crawled into view through the haze and the gunpowder-fouled air. Shrouded in fumes, its engine roaring, he’d already guessed it did not belong to Germany. The number 102 and a red star marked its turret.

And its commander must have noticed this curious phenomenon, for the tank stopped, turned with a rattle, and drove through the opening.

Julius stared, flat on the dirt, his mouth hanging open.

Another tank arrived, turned, followed after the first. And another after that…

THE END

Copyright Douglas Kolacki 2021