Chess in Hanoi by Gary Ives

Chess in Hanoi by Gary Ives

This is about my cousin Gordon who grew up rough. Nobody, including his mother Thelma, knew for certain who his father was, only that he was black. Sadly, his mother who was my aunt, a drunk and a pill freak, was hardly the ideal mother. By the fourth grade Gordon knew how to get himself fed, dressed, and off to school unassisted. Whenever Thelma, who was my dad’s half- sister, pulled one of her frequent disappearing acts, my dad would fetch Gordon to stay at our house. My mom would launder and press all his clothes and often buy him a new pair of shoes or trousers. In the seventh grade his residence with us became permanent when Thelma took a header off the Stoker Island Bridge.

Until I went away to university, we shared a bedroom. Gordon was obsessively neat; I wasn’t, but he never complained about my piles of clothes or junk; he kept just the areas around his desk and our bunk beds tidy. Because there was a tiny reading lamp on the bottom bunk, he asked to sleep there while I preferred being closer to the ceiling fan as it’s hum seldom failed to lull me to sleep. Gordon often read until late. Sometimes we lay chatting into the night.

In grade school he had been picked on. This for a variety of reasons: He looked more negro than white, he was tiny, he had often worn the same unwashed clothes for days on end, he wore glasses, and because our school was rife with snobbery as are most schools. True, our school was in an affluent district which seemed to expose and accentuate his poverty. In seventh grade, with his nose broken, bruised and wonky, he faced an expulsion hearing for having broken the wrist of an eighth grader who had called him ‘nigger boy’. Fortunately, my dad, an attorney, stood by his nephew and nothing other than the disfigured nose came of it.

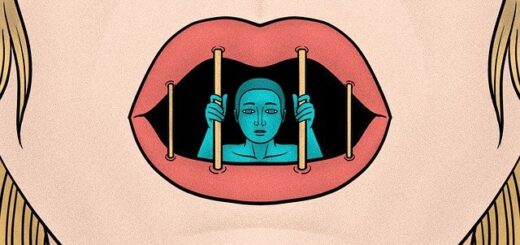

My father did not often show affection, not that he was cold, he was just a quiet, taciturn man. I still harbor a suspicion that Dad preferred Gordon to me as Gordon was more like him and, truthfully much smarter than I. However, I was not jealous as he was not only my cousin but my best friend, by far. We shared confidences and covered for each other’s peccadilloes. Soon after he’d come to stay permanently with us, dad bought us chess sets and taught us the game. We devoured chess and must have played thousands of games during our high school years. Gordon beat me at least three out of four times, but I won enough to present a challenge. Dad, however, usually kicked his ass all over the chess board. Yeah, chess was big at our house. Our two cats were called Bishop and Rook.

Although Gordon was an outsider who truly loathed the fucked up social-side of school, quietly he learned. Other than phys-ed, he could pull value from every course he took, and actually liked math courses, Latin, and even wood shop. He was a good student, a quiet and steady worker, the kind most teachers appreciate, however most of his teachers simply overlooked quiet, dark-skinned, little Gordon Fleck.

While he had a strong bent for academics, it is odd that wood shop was his favorite class and, as it would turn out, his most important course, as Mr. Abrams his shop teacher in tenth grade, was the only teacher to recognize that special thing in Gordon, and to take a liking to him, and that good man introduced Gordy to his personal hobby – wood carving.

Noticing a talent Gordon had working with a chisel one day he asked, “Would you like me to show you how to carve?” He first taught Gordon how to carve simple things like boats and cars from small blocks of soft pine. Later he presented him with a simple two-dollar Barlow pocket knife, though he insisted Gordy exchange a coin for the knife, the superstition holding that such would prevent the knife from cutting friendship. “The Barlow has a carbon steel blade that’s easy to put an edge to.”

Gordy indeed had a knack for this, and Mr. Abrams advanced his instruction to more difficult subjects like animals and bas reliefs executed in hard woods. He carved dozens of beautiful little figures during that year, improving steadily. By the end of his senior year, he had become an artisan. For the last two years of high school, after the last bell of the day, Gordy would trot down to Mr. Abrams wood shop and while the two sat and carved they would talk politics. Mr. Abrams was probably the only liberal teacher in the entire school.

My Aunt June ran a small gift shop at the hospital and sold every piece she could finagle out of Gordon; he was that good. He could carve anything – horses, dragons, any kind of fish or sea creature, but he particularly liked carving little images of people with exquisitely detailed faces. He had a knack of caricaturizing faces in wood. In our senior year he and Mr. Abrams split a thousand-dollar prize for their joint project ‘The Three Faces of Elvis’ in walnut which took first place at the state fair’s art festival. He did stunning nine-inch bass wood busts of my mom and dad. He always carried a chunk of wood with him along with his trusty Barlow pocketknife and a piece of sandpaper.

Wood carving was not the only new find from Mr. Abrams who also introduced him to the ideals of the left. He gave Gordy a well-worn little paperback copy of The Communist Manifesto. Gordy became so engrossed in the little book he must have re-read it a dozen times. Within a few weeks the little book was ragged, dog-eared and full of Gordy’s penciled notes. At night as we lay in our bunks, he would read portions to me.

“Man, this shit is so good,” he’d say, “think about it. What if the whole world was classless and everyone equal with free public education and public health for everyone? Think of it Billy, women equal to men, Blacks, Asians, Indians equal to you almighty Whites. No kings, no popes, no industrialists controlling the masses with soldiers and police and superstitions. Marx has this greed thing nailed, Billy. I can so dig it.”

Maybe I could dig some of it, but hell’s bells it was communism. “Damn it, Gordy, your hero is the original fuckin’ communist. They’re the enemy, buddy. Doesn’t that say something to you?”

“Ism’s schism’s, Billy, I dig the message. Marx explains so well why, so many things are fucked up. Why there is poverty amid wealth. Capitalism stokes greed, Billy. But I know what you’re saying. Yeah, the Russians and the Chinese come down hard on their people. Dissent will get a body locked up. That’s wrong, but see, that isn’t what Marx was about. Also, despite their leaders’ heavy handedness, the Soviet Union and Red China have taken quantum leaps forward from the bad old days of czars and war lords. Cuba too. There’s full employment, free education and health care, good public transportation and improved housing. But here in the industrial world the difference isn’t so much a matter of want as it is greed, unfettered greed. Look at all those shitty rich kids at school. Strip them of their fifty-dollar sweaters, their hundred-dollar gym shoes, their cars, their parents Country Club elitism and they’d probably be decent without their well-taught, greedy senses of superiority and class. It’s like a virus passed from parents to offspring. You don’t know how good it felt to twist that fucker’s wrist until it snapped, and to hear him beg for mercy. Even then I wanted to piss on the rich puke. I don’t know yet how I feel about communism. Seems like the Soviets and the Chinese have twisted it way too tight; yep, there’s a dark side to their brand of communism. What I do know though is that I share the ideals in Marx’s little book, and that I can see clearly that there’s also a nasty dark side of capitalism. And don’t worry Billy, I don’t talk about this with anyone except you and Mr. Abrams, and he’s cool.”

I asked him if Mr. Abrams was a communist?

“Definitely not,” he said, “Mr. Abrams said he would never join any political party, especially one that’s so hated in America. He told me, ‘Gordon, I’d bet that you, like me, will never join any party; there’s more anarchist than socialist in you. Eventually all political parties fall out of favor. When they get defensive, they become dangerous. You need look no further than Senator McCarthy.’ He said that governments put names on list and will come after you like they did in Hollywood. Besides, I like some, not all, of Marx’s ideas.”

Still, I could not understand this; I worried about his flirtation with such a fucked-up ideology. “Well, I’m thankful you know that it’s best not to air that in public.”

I felt honored that he’d discuss his burgeoning views on capitalism and socialism with me but not even mom or dad. Still, his notions were fucked up. Shit, you’d think that everyone knew that communism was bad news.

Dad kept a sailboat on the lake and that’s where Gordy and I spent weekends and summers sailing. Gordy had a part-time job at the boat works. We loved the water and he loved boats. Sometimes he talked about joining the Navy; he loved anything nautical. The sailboat was a draw and we could sometimes pick up girls from the vacation cabins, but none of the things we’d hoped for ever even came close to happening.

In 1965, I went off to the university while Gordon elected to stay at home to attend classes at the community college and work at the boat yard. His introduction to higher education must have been poor. His letters complained of ‘professorial arrogance’ and incompetence. He was quickly done with it. At the end of his first semester, he dropped out.

He attempted to join the Navy but could not pass the physical because of a heart murmur. However, he applied to, and was accepted to the Merchant Marine Academy at Kingsport where the examining physician either missed or overlooked the heart murmur.

There, his neatness, intelligence, and diligence served him well with his graduating in three years with a bachelor of science and a United States Coast Guard unlimited license as a Merchant Marine Officer with a Third Mate ticket. He came to my graduation ceremony in his Merchant Marine Officer’s uniform looking so smart.

Normally, Merchant Marine Academy graduates are automatically commissioned as Ensigns in the Naval Reserve; Gordon’s heart murmur and deteriorating eyesight however disqualified him from this usual commissioning. He had two weeks leave before reporting to his first billet as Third Mate aboard The Mercury Flyer, a cargo vessel under Panamanian registry. I had little time to spend with Gordon as I had become engaged to be married and would begin law school in a week. Before we parted, he gave to me a beautiful polished cherry wood bas relief of the two of us, head-to-head, over a chess board, our clearly identifiable faces set with determination. It is the thing I value above all other possessions.

Gordy loved going to sea and he loved his ship. I received his post cards and occasional letters from exotic places like Singapore, Manila, Sydney, like this from Djakarta:

Life at sea suits me fine, Billy. There’s a general air of equality and a man is respected pretty much on how he performs his work and the honor of his word. No one gives a shit who you might have been or where you came from as long as you work hard and are fair in your dealings. Our crew is an international mix of Lascars, Filipinos, Chinese, Americans etc. Some with pasts it’s best not to ask about, something which bothers no one. Our captain is a 70-year-old Greek with 55 years at sea. I work for the chief mate, Mr Jolicoeur, who, while rather disdainful of Merchant Marine Academy graduates (who he refers to as sea pussy) has taken to pushing much responsibility upon me. He insists that I am present on the bridge for any evolution, especially navigation tasks like shooting the stars, and he has me in the holds when we take on or off-load cargo. He even had me operating the cargo boom when we took on containers of furniture in Manila! I knew I was gonna love this life!

After the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, the war in Viet Nam intensified and I counted ourselves lucky because I qualified for a college deferment and because Gordy’s heart murmur protected him from military service. However, after only two years at sea, he failed a requisite annual visual acuity test and sadly, he lost his ticket, thereby ending his beloved merchant marine career. I knew his loss was a crushing blow, and I worried over its impact upon my best friend.

His letters began reflecting an uncharacteristic sour state of mind, and were filled with complaints: Despite his qualifications he was having trouble finding a decent job that offered a future; he felt he was a failure. This self-pity was for him abnormal, but understandable. Gordon was not a ‘people person’ and I reckoned this dark mood dampened his job interviews. In his letters he blamed potential employers, labeling them racists and dumbshits. Too, he ranted at what he termed ‘the criminality’ of the war in Viet Nam. Using his savings he began travelling from port to port up the coast in search of a nautical job. Ultimately, he found a good position managing the office of a Canadian company in Vancouver, Pacific Crest Shipping. There he threw himself into learning commercial maritime laws and shipping regulations. And there he had his first love affair, this with a forty-year old secretary in the ILO office, Ruby Carrington who happened to be a bona fide card carrying communist.

Beginning work in the Pacific Crest office, Gordy had not yet recovered from the depression he’d slid into when his career at sea collapsed. Until Ruby, his salvation had been work, where he had buried himself in learning maritime law and in managing the office on the docks of Vancouver.

Week by week he absorbed maritime law, torts, and contractual law at work. And week by week Ruby Carrington drew him out of the fog of gloom he’d suffered for a year and a half. Warm, sensitive, and nurturing, her attentions and intelligence restored balance to Gordy’s life. He at last had an ear that would listen to him, and Ruby understood him with a depth I probably never achieved. The two lovers picnicked in Stanley Park and took Sunday dinners in Chinatown. His heart soared when she invited him to move in with her. Ruby’s friends, including a few fellow communists and Gordy, enjoyed discussions they’d have over big spaghetti and wine dinners twice a month at someone’s apartment.

While friends pinged on him to join the party, Ruby did not, as she knew his feelings. His bent toward socialism was strong, but so too was his skepticism regarding the harder aspects of life in countries under communist party control. Ruby’s friends acknowledged such problems but advanced that only with a younger generation would justice be able to rise. These young communists believed that youth and time would lead the world ultimately and inevitably to the worker’s paradise. It seemed to him that their young minds were clouded by the romanticism of the movement. He scoffed at their Che Guevara tee shirts. Although Gordon disagreed, he was energized by the arguments.

One issue on which everyone agreed was the travesty of the American war in Vietnam. There was fervor among most Canadians against the war. Some even travelled south to attend anti-war protests in Seattle and Portland, and on the docks, Ruby’s ILO gang bosses were giving preferential temporary hiring to American draft-dodgers and deserters. For his part, Gordon had several anti-war letters published in The Vancouver Sun. His letters to me from Canada showed that he had come out of his funk.

“These Canadians are so much like us in speech, tastes, and mannerisms but socially and politically much more conservative. Also, they enjoy a national pride we seem to have lost. Ruby has been a godsend. She’s opened some of the windows I’d closed when I lost my Third Mate’s ticket, she’s led me to see that there are some good people out and about. Her coterie of intellectuals gathers twice a month for wine and spaghetti and late-night discussions like you described at your university. It’s stimulating. She’s a peach, I tell you.

My work goes very well. Pacific Crest Shipping is a small fleet of three RO/RO (roll on/roll off) container ships working Pacific ports. Get this– last year we trafficked twice in Haiphong – that’s in N. Viet Nam! Even though up here they are very conservative politically, just about everybody. excepting some military and old men, is against the American involvement in Viet Nam. Canada ain’t at war, god bless ’em.

Our company’s owned by a consortium of wealthy Canadian-Chinese who live here in Vancouver. My boss, the General Manager, is Anthony Yang whom I very much like and admire. He tells me he’s grooming me to take his position, and has taught me much. He’s very bright and hard-working. Some nights we don’t close the office until ten o’clock. Good work and a good woman– what more does one need? Speaking of good women, Ruby and I are flying in for your wedding on the 16th, you lucky duck! See you then, Billy Boy.”

About a month after the wedding Anthony Yang asked Gordon to a private dinner at the Hotel Georgia with two of the powerful men from the conglomerate. There they confided to Gordon that they and other members of the consortium were ready to make Anthony a partner. Further Anthony had convinced them that Gordon had been a rare find, a treasure and would be fully capable to fill his old job as General Manager. There was one caveat, the old men demanded Gordon sail one voyage aboard each of the company’s ships. This would allow important personal interfaces with ship’s masters and sea-going officers and allow Gordon to observe how well company policy is carried out at sea. This, to the consortium was crucial.

When Anthony asked if Gordon had any objections to going to sea for a few months, Gordon’s face beamed. “Are you kidding, Tony; just throw me in that briar patch.” Later he suggested that he sign on as purser rather than passenger. Everyone loved the idea.

He signed aboard the Pacific Jade Star as purser one day before the ship completed loading and sailed for Honolulu. From there the ship would discharge and load cargo in Singapore, Djakarta, and Yokahama before its return to Vancouver two months later.

The purser’s job was simple accounting and administrative duties dealing with port authorities, but he took pains to do extra favors for the officers and crew, like getting a crew member’s visa renewed in port, or taking pains to secure the freshest lobster, choice cuts of meat, and fresh fruits for the mess. Jade Star seldom spent more than two days in port so there was scant opportunity for sight-seeing or pleasure. He relished being back at sea and spent as much time on the bridge. Captain Capello, as salty as they come, loved to spin yarns seated in the elevated captain’s starboard swivel chair. As Gordon was a good listener and loved ships and the sea, the Captain and Gordon struck a good rapport.

The voyage was a complete success. Back in Vancouver, Gordon handed Anthony Yang the detailed report on Jade Star’s operations including facts, recommendations, and opinions. So impressed were the old men of the consortium that they awarded Gordon a thousand-dollar bonus before he set sail on his second voyage aboard Pacific Crest’s Lotus Dream.

Upon sailing, Lotus Dream’s only known port of call was Osaka to off-load twenty-two frozen food containers and take on seventeen units of televisions. To reduce time in port, container ships often sail knowing only the next port of call. Like most shipping lines, Pacific Crest relied on radio communications to provide updates to itineraries. Midway across the Pacific, orders came for Lotus Dream to take on containers of truck parts and motorcycles in Hong Kong for delivery to the port of Haiphong.

Aboard the ship were seven Americans whom the First Mate called into a meeting. While in Haiphong they would under no circumstances leave the ship, and they were ordered to not even approach the brow. He explained that the North Vietnamese would know Americans were aboard from the crew lists required by the Harbor Master. The protocol specified that as long as American crew did not set foot on North Vietnamese soil their safety would be honored. There had been no problems to date.

So busy was the Port of Haiphong that the Lotus Star had to wait two days moored to a channel buoy in the roads among other ships in line, while Chinese and Soviet cargo ships discharged priority military cargo. That first night in the roads Gordon was seized by an acute pain in his belly. Next morning this was febrile, nauseous and the pain increased. It soon became clear that he was suffering an appendicitis attack. First Mate Jollicoeur, a Canadian, radioed ashore for an ambulance. As he stepped from the radio room, he ordered Gordon carried into the ship’s boat.

First Mate Jollicoeur personally delivered him pier-side to a battered Datsun pickup truck painted with a red cross. On the way to the hospital Gordon’s appendix burst. His next two weeks were in the Haiphong Hospital as he slowly recovered from acute peritonitis. He would later learn that without the Lotus Star’s complete inventory of antibiotics from the medical locker, twenty lbs. of tinned coffee, and a case of Johnny Walker Red hand delivered to the Viet hospital one hour before Lotus Star’s departure, by First Mate Jollicoeur, Gordon would surely have died.

The first Vietnamese phrases that Gordon would learn were for “Thank you, doctor, thank you nurses,” this learned from Dr. Bac-Si Wang who had performed three belly surgeries on him, it was a week after his last surgery before he was able to sit up.

Kindly old Dr. Wang informed him that his ship had sent his possessions ashore before sailing and he could have these when he left the hospital. “First some officers must see you. Please remember to be very respectful, do you understand?” Aware of his precarious position, how could he be anything but respectful? Two uniformed officers, a man and a woman came to his bedside to interview Gordon. From his pillow, he bowed first to the man, then to the woman and addressed them with the traditional Vietnamese greeting he’d learned minutes before from Dr. Wang.

Addressing him as Mister Fleck, they asked his military status. Each was very stern in demeanor. The man questioned why he held no commission in the Naval reserve. Dr. Wang was summoned and listened intently at Gordon’s chest for three minutes then confirmed his heart murmur. “Since your country is at war with The Democratic Republic of Viet Nam, you are enemy,” the woman informed Gordon. “You must come with us.” Over Dr. Wang’s protests, Gordon was placed on a stretcher, carried to a battered taxi then driven propped-up between the two officers in the back of the tiny taxi to a prison located in a village some fifteen kilometers from Haiphong. There he was placed in a cell by himself. And there Gordon would slowly and painfully recover, regaining his strength little by little while learning the language and customs of Viet Nam from one of his jailers, Ong Le, a former teacher, now a soldier who had been drafted, and who was studying English.

Ong Le had a gift for simplifying instruction, and teaching Gordon, a Westerner, the nuances of the tonal language. All lessons began with drills which stressed each of the tonal inflections. After each practice session Ong Le and he would exchange a list of fifty words to memorize by the next day. Gordon always ended his list for Ong Le with a colloquial phrase, like “See you later, alligator.” Within three weeks, his coherent sentences could be easily understood and by six weeks he surprised himself one night by dreaming in Vietnamese, so easily did the language come to him, much to Ong Le’s credit.

Once Gordon became ambulatory, he was sent out on work details sweeping streets, tending graves at a military cemetery, or cleaning fish. The street sweeping detail was detestable as residents always stared and sometimes cursed him and even spat upon him. Children, when no adults were present, would approach at times to touch his dark skin or his hair. On work details the food ration was a meager rice ball and bowl of soup daily. On good days the soup would contain a small piece of fish or pork.

Back in his cell officers came to interrogate him, asking the same questions over and over. “What is your military status? You are Navy Officer, yes? Tell us the truth, Mr. Fleck.” And over and over again he recounted his history. He was forbidden to talk or interact with the other prisoners and was the only one in a private cell. He was permitted to speak only with the military men in charge of the jail. These were wounded men reassigned from combat to home duty. The peacetime jailers and town policemen had been drafted into the army leaving wounded military replacements to supervise the small prison. The jail’s prisoners were Vietnamese charged with stealing, avoiding the draft, or desertion. Perhaps as soldiers his keepers intrinsically knew that Gordon was not military, but they were curious about the life of their negro American ward.

Technically he was not a prisoner of war; his confinement was a precaution to protect the people from the influence of spies and foreign provocateurs. Consequently, his keepers, while initially aloof, were not cruel in their treatment of Gordon as they would have been had he been a military POW. His food ration improved. He was told that he was not a prisoner.

When he asked, “If I’m not a prisoner, what am I, and why am I in jail?”

“You are ‘special category foreigner’, Mister Fleck, maybe later you are prisoner of war. Now you are ‘special category foreigner’, don’t ask questions. Only thing, just be good.”

One sunny morning he was issued a new set of pajamas, escorted by two soldiers to a jeep, driven back to the hospital in Haiphong, and placed in freshly made bed. Friendly old Dr. Wang came into the room smiling and asking to see his scar. Examining him he spoke in a low tone. “Some people come here to make pictures. Very important. You must smile and show appreciation. Do you understand?” Indeed, later that morning three Germans came to his bedside, two men and a woman. One man set up still and motion picture cameras while the other rigged a microphone on a boom over Gordon’s head. The woman introduced herself as Gertrude Schlosser representing the newspaper Nueus Deutschland. The brief interview was a pleasant change from the routine of work details. Yes, he said, the North Vietnamese, have treated me decently, considering my country is at war and currently bombing innocent civilians here. He praised Dr. Wang and the nurses at Haiphong Hospital and said that he admired the courage of the Vietnamese people. No, he had not been in contact with any military prisoners of war. It was a short interview. The Germans’ larger interests were scheduled interviews with captured American flyers. Frau Schlosser and her engineers thanked him and presented him with a few flat tins of German cigarettes. He’d give half the cigarettes to Dr. Wang and trade the others to the head jailer, Sergeant Bui. The empty tins he would keep.

Several kilometers to the north and to the west of the prison’s village were air bases, which the Americans frequently bombed usually at night. On those nights guards and prisoners trooped outside into sand bag bunkers to feel the earth shake, to breathe dust, and fight mosquitoes by the dim yellow light of a single candle. The bombings were so frequent that most had adopted a stoic attitude and took the bombing as a routine annoyance unless personal losses were experienced. Sometimes people and structures nearby were hit. Gordon spent an entire week on a work detail alongside townspeople repairing a heavily damaged bridge. He admired these little people’s pluck in the face of such powerful giants.

Sometime during his third month he was given his small bag of personal possessions which the ship had delivered to the hospital. Most welcome were socks, shoes, and a shirt. On afternoon, he noticed Sergeant Bui, the sergeant in charge, paring his fingernails with his own beloved old Barlow.

Gordon bowed. “Sergeant, you have found my lost knife. Thank you. Please will you return it? I have carried that little knife for ten years. Since I was only this tall.”

A wry smile crossed the sergeant’s face. “No, no. Not yours. This knife is mine, similar like yours maybe. I have for eleven years.”

Bowing once more, Gordon replied, “I salute your very good choice of knives. If you were ever to think of acquiring a better knife, I would be disposed to trade this wristwatch.” In this bargain his eighty-dollar Seiko changed hands for his beloved two-dollar Barlow. Included in the deal were the last of the German cigarettes and the sergeant’s guarantee that Gordon could keep his knife, despite the jail’s regulations.

The diversion the knife provided was a godsend to Gordon. In the evenings, he set about wood-carving. His first project was a little bust with the sergeant’s face sternly peering beneath a military helmet. This present greatly impressed the sergeant and was followed by little busts of the other three guards. These treasures and his improving linguistic abilities warmed them to him and he sometimes found an extra ration or a candy in his cell. The soldiers eased into a familiarity, softened the tone of their voices, and spoke easily and friendly with Gordon, a serious student of their language.

Sergeant Bui, career NVA with eight years’ service, had been sent south two years earlier in charge of a mortar crew. He’d taken a serious shrapnel wound in his right leg during an American artillery barrage, had been given first aid, then placed on a truck packed with other wounded to be hidden under the forest’s canopy during the day then driven for two nights back north. He limped and sometimes Gordon could see him wince, but he did not complain and did not relate war stories even when Gordon pressed.

Of the others, two were young, maybe nineteen or twenty, volunteers and Ong Le, his teacher, who was a thirty-year-old draftee. All had been sent south and all had suffered debilitating wounds that put them out of combat. The boy called Vinh had survived a bullet through his neck which left his head in a permanent position, requiring that he turn his entire body to adjust his field of vision. Trinh, the other boy had lost most use of his left arm from burns, probably from white phosphorus or napalm. Ong Le had lost an eye.

Considering that each one’s experience in the south had been grim, they were visibly appreciative of the soft duty minding this small prison, thus serving the war effort by releasing the regular civilian crew for induction and service down south. Both boys looked up to Sergeant Bui and always seemed eager to please. Ong Le, educated and older than the others, was called uncle. Sergeant Bui had status from his years’ service in the army and rank as well as a likable nature. Too, he had been decorated for ‘heroic valor under enemy fire.’

Since the trading of the Seiko for the Barlow, Sergeant Bui had warmed to Gordon. All of them were curious to learn about Americans. They asked the cost of everything: bread, bicycles, cars, rent, motorcycles, shoes—everything; they wanted to know how much American soldiers were paid. When he estimated that a soldier of equal rank and time in service to the sergeant would probably earn about $400 monthly, they initially refused to believe him. Were negroes paid as much as whites? Had the police ever sent attack dogs after Gordon or other negroes he knew?

One day, upon returning to his cell from work detail, on the little table lay a box covered in inked stamps and seals. The care package Anthony Yang had sent two months earlier containing: vitamins, coffee, tinned bacon, and Heath Bars. A note read: “Hang on Gordon, we’re working to get you home.”

As his keepers relaxed and grew more and more comfortable with him, life eased. No longer did they lock his little cell which they called his ‘tiny house,’ and often they shared leftovers and tea from their meals; Sergeant Bui even brought him candles. Only when foreign journalists were in the town did he have to go out on working details. He was still forbidden to mix with or even talk to real prisoners in the jail. Clearly, he enjoyed a special status.

Gordon set about carving a chess set. He dove into this project and carved the king, queen and bishops as traditional figurines however his pawns wore the conical straw hats of Southeast Asian peasants carrying Kalashnikov rifles, and the knights were erect, stern-faced uniformed NVA. The figurines were quickly and roughly carved, without Gordon’s usual finesse and attention to finer details; still, the project took two months to complete. The chess board he fashioned from bamboo strips, half of which he’d darkened in a tannic acid solution he’d made from bamboo leaves and urine in the German cigarette tins. Playing chess with the now good-natured sergeant broke the dullness of the rainy monsoon afternoons when wind and rain beat upon the tin roof.

One such rainy afternoon, the sergeant handed Gordon a tattered envelope, date stamped forty-five days earlier from Vancouver, B.C.

“Gordon, I cannot detail all the things we’ve done, but prospects are looking positive for your release. I have an appointment with someone in the North Vietnamese Embassy in Ottawa this Friday. I will deliver to them letters for you from Ruby and your family, copies of the Vancouver Sun in which your anti-war letters appear and an affidavit your lady friend Ruby obtained from the Chairman of the Communist Party in British Colombia verifying the party’s knowledge of your strong anti-war stand. Keep strong. Keep the faith, my very dear friend.”

This buoyed his spirits immensely. He felt so good that he allowed the sergeant to win two games that afternoon. He would never learn that Anthony Yang had negotiated a bribe of several thousand dollars for Gordon’s release. Gordon stayed strong and he kept the faith and sure enough, just before Thanksgiving, he was escorted by two soldiers to a Dutch container ship whose next port of call was Long Beach, California. Before leaving, he shook hands with Ong Le, thanking him with a gift of his empty cigarette tins and socks. He smiled at his teacher and said, “See you later, alligator.” Ong Le replied, “After a while, crocodile.” To Sergeant Bui, he presented a little bas relief of himself and the sergeant playing chess, probably like the one he gave me. Sergeant Bui in turn presented Gordon with an elephant hide billfold in which he included a picture of himself with his wife and two small children. On the reverse of the photograph, Sergeant Bui’s address and this note, “Maybe after we win this war, you and me friends, yes?” To the good doctor Bac-Si Wang, he presented the rough carved chess set which brought tears from the old man.

During the crossing aboard the Haarlem Droom, Gordon would gain five pounds and remain in a state of continual wonder at the three meals a day, each with meat, of hot water, of hearing English spoken, of clean clothes, and of laughter. Captain De Groot welcomed him on the ship’s bridge during morning hours and entertained him with sea stories and cups of delicious, rich, hot chocolate. Late afternoon and evenings he napped or played chess with the crew. The radio officer sent radio grams to Ruby, Anthony, and to family.

Entering Long Beach harbor, the ship’s lookouts reported an unusual crowd at the assigned loading pier. Captain De Groot addressed the mate on watch, “Ah, must be for our good passenger.” With a pair of binoculars Gordon’s scan of the pier caused his heart to skip a beat when he spotted Ruby, Anthony Yang (in a smart blue suit) standing next to my mother and father. The binoculars did not reveal that among those present, were two federal agents from the FBI who promptly and professionally placed my cousin Gordon Fleck under arrest and escorted him through the crowd to a black station wagon which drove him to the Federal Corrections Facility, Terminal Island.

My cousin was charged with violation of the ‘aid and comfort to the enemy’ clause in the treason statute, confined, and informed that he faced a possible sentence of life in a federal penitentiary.

My dad, a lawyer, was present at his bail hearing which lasted all of five minutes and which denied bail to Gordon. The government’s case against Gordon rested on an interview published in the East German newspaper Neues Deutschland picturing Gordon smiling from a hospital bed and in which he praises the North Vietnamese war efforts, and from a newsreel from Soviet Television showing Gordon filling sandbags with North Vietnamese workers at a bombed-out bridge reconstruction site near Haiphong.

The Government’s lawyers offered a deal. In return for Gordon’s guilty plea, the government would agree to a one-year sentence at the Federal Minimum-Security facility located on Eglin Air Force Base in Florida nick-named Club Fed. Gordon would have extraordinary privileges and even be able to leave the facility under certain conditions. In the froth and momentum of the anti-war movement, the government was extremely anxious to prevent Gordon from becoming a poster boy for the movement. Just that spring, upwards of a quarter of a million anti-war demonstrators had marched on Washington.

When I visited him at his Florida facility, he told me that dad wanted to fight the case in the courts, but Gordy did not. He shared the government’s fear that he would become a celebrity. He would heed Anthony Yang’s advice that upon his release he would quietly apply for Canadian citizenship.

The Federal prisoner facility at Eglin Air Force Base was a special ‘country-club’ spot for convicted politicians, judges, and special non-violent politically sensitive cases like Gordon’s. Quarters were the top floor of a modern enlisted men’s barracks with two to a room and shared bath, and a recreation lounge. His roommate was a hugely fat former state legislator convicted of accepting bribes. Gordon’s duties consisted of trimming hedges and raking sand traps at the air base’s golf course three days a week. Twice a month, he could be signed out for three hours by family members for lunch in town.

The year’s confinement returned him to his chief diversions, reading and wood carving. Ironically, his sentence afforded him the freedom of the leisure time that would result in his achieving not only retribution for his government’s shabby treatment, but wealth as well.

It was during this time that I was recruited to act in secret as Gordon’s agent in a matter he wished kept from the government. After his return from North Vietnam, a flurry of letters flew between him and Ruby. She visited him shortly after he arrived at the Florida facility and during that visit, plans were laid. One week before his scheduled release, Ruby would again visit.

Carrying Gordon’s identification and a Power of Attorney I had picked up at an office supply store, I presented myself to the clerk of the court for Okaloosa County and with Ruby, I obtained a marriage license in Gordon’s name.

“He’s in the hospital for a liver transplant.” I lied. “It’s important that Ruby and he marry before the operation. I hope you can understand the urgency, sir.” That done, it was no problem to find a willing minister. There are more preachers than mailmen in Florida.

I was able to sign Gordon out for an afternoon luncheon one afternoon, just two days before his release. On the dining deck of Franco’s Fantastic Seafood, overlooking the Gulf of Mexico, Gordon and Ruby were married by the Rev. Jojo Sledge of the Calvary Temple Gospel Church who finished the solemn vows with the flourish of, “I now pronounce ya’ll man and wife. You kin kiss the bride, sir. Halleluiah, Praise the Lord!” My parents, Anthony Yang, and I felt as though we had pulled a fast one on the government, and we were quite merry. However, if we had known the true state of Gordon’s health, we would not have felt such joy. Only to Ruby had he disclosed that he had returned from Viet Nam with a heart condition.

The honeymoon in British Colombia was kicked off with a spaghetti dinner attended by a host of old friends, longshoremen, Pacific Crest employees, and communists who presented the happy couple with a week’s stay at Giant Bear Lodge at the north end of Vancouver Island.

As mentioned earlier, Gordon had returned to his beloved avocation of wood carving. The rough set he had executed in N. Vietnam and presented to the good Dr. Wang had inspired him to carve another, and with the gift of time imposed by the sentence, he intended to perfect the figurines, to be done this time in much greater detail and in hardwood to be finished smooth. I was able to deliver seasoned chunks of live oak, an extremely hard wood. Old Ironsides, in fact, had been constructed of Florida live oak harvested from the Gulf coast not far from where he was confined.

The white figures, the N. Vietnamese, whose pawns, the same Viet Cong soldiers in conical bamboo hats and bearing AK47 rifles, were executed in minute detail. Each rook was a round pit of sharpened punji stakes, knights were helmeted NVA solders holding rifles at port arms with fixed bayonets. The two bishops were images of the hero General Giap in splendid uniform. The white queen was a uniformed North Viet Nam Army woman, representing the many female soldiers. The king was none other than the venerable Ho Chi Minh.

Carved in walnut, the black side’s king was a grinning Richard Nixon leaning in a forward slouch, rubbing his hands together. His queen, the unmistakable image of evil Dr. Henry Kissinger, standing expressionless with briefcase in hand. Detailed images of the bespectacled, flat, sour face of Robert McNamera served as bishops, helicopters for knights, and delicately carved aircraft, their wings armed with bombs and missiles, served as rooks. Pawns were helmeted GI’s with M14 rifles with fixed bayonets.

At the time of his release, Gordon had not finished carving the final figures of the fighter aircraft. These he finished in Canada some months later, carving the most difficult pieces by copying details from a plastic model of the A4 Skyhawk. The chess set was exquisite; each piece hand polished in a natural finish, white in live oak, black in rubbed walnut. He was immensely proud of this work of consummate artistry. He sent photographs to his old mentor Mr. Abrams. It was his best work.

The Sunday Vancouver Sun ran a two-page feature on the carving of the chess set. The paper hailed Gordon as ‘one of Canada’s premier artisans’, a tribute not missed by the office of immigration. He had been relying on his marriage to Ruby to ensure approval of his request for Canadian citizenship. A week following the publication, his application was approved, and he was sworn in as a Canadian citizen. The feature drew attention from other media and soon Gordon received occasional requests for interviews and photos from newspapers and magazines, some foreign.

One visitor was a Mr. Clive Jamison representing the company that had made the plastic model of the A4 Skyhawk. Mr. Jamison, like Gordon, was black and like Gordon had been a picked-on, introverted boy who had been fascinated with constructing models from materials he found. His love of model making had led him to his job. The two men instantly became friends.

His company, he said, would like to use his images in small plastic figurines for cheap chess sets to be made available in several hundred retail outlets in North America and Europe. Gordon would receive an up-front payment and royalties from each sale.

As an aside and on a personal level, Mr. Jamison further suggested that Gordon have the figures cast in their larger sizes in bronze and copper. “Listen, Gordon, put these on an eighteen-inch leather board and you can command five or six hundred dollars a set. Think about it, Gordon. If you’re interested in doing that, I’d like in on it.”

“The money’s not important,” Gordon told him, “but I do so like the idea.”

By the end of his first year in Canada, in partnership with Anthony Yang, Clive Jamison, Ruby and me, the Art of War Company was launched in Vancouver naming Ruby Fleck president and general manager. Gordon preferred to remain a silent partner.

“I don’t give a shit about the money. I’ve got Ruby,” he told me, “she’s all the wealth I need.”

He did insist, however, that the casting of the chess pieces be done in Haiphong. The $150,000 invested by the company would be recovered by the first few month’s orders.

Photo ads in prominent newspapers and magazines in North American and European cities were met with an explosion of orders. Art of War expanded from a rented office to its own office building in Vancouver, and the Nha Do Foundry in Haiphong hired additional employees to meet the demands.

Gordon was proud that sixty-two individual orders originated from members of the United States Congress. Ironically, the figurines were cast from smelted brass artillery casings and copper wire salvaged from military wreckage.

Soon after President Nixon’s 1974 resignation, Gordon was quoted in an interview, “I’m proud to have had small part in memorializing this most delicious and historical checkmate.”

Ruby and Gordon would have two healthy children, a boy called Anthony and a girl Emma. My father worked tirelessly for an appeal to Gordon’s conviction, and in 1978, Gordon received a full pardon from President Jimmy Carter. Sadly, this pardon came just three days before Gordon suffered a fatal heart attack in Vancouver.

By the terms of Gordon’s will, initial grants of $50,000 followed by twelve percent of Art of War, Ltd. profits sponsor an orphanage in Haiphong and another for mixed-race children in Ho Chi Minh City. All of us miss my beloved cousin Gordon Fleck: hero, artist, and Canadian citizen.

THE END

Copyright Gary Ives 2021