No Doubt About It by Tony Billinghurst

No Doubt About It by Tony Billinghurst

Real people can’t find me. Even if they search through all the dead end towns in the world and get the right one, they won’t find the alley, locate the building or get the right floor as my rooms are hidden and anonymous. My name isn’t by my doorbell – no one need ring it anyway; I don’t answer as every caller is the bearer of grief.

I live alone and visitors to my studio are prohibited. People, the lot of them, come with their hands out wanting something, a piece of me, or my vote or to sell me something I don’t need for money I haven’t got, or worse, they’ll be irate customers after my blood or cops wanting my liberty.

On rare occasions when I want company, my imagination creates guests for me, like you. Don’t look so surprised – you are a figment of my imagination. All my creations, at their worst, are more agreeable than reality, but I warn you, when I’m done, I snuff them out, and you’ll be no exception, so don’t start whinging. Right, move my dinner plate off that chair and sit over there.

You want to know what? Well – ok, I’ll tell you, but it’s strictly entre nous – understood? Right, I’d better check around first, you can’t be too careful, there are ears everywhere, what with the police for one and ‘them’ for another.’

I peeked out of my front door then closed and locked it, closed the windows and pulled the curtains. Ok, keep your voice down and move closer. Now, days were when my paintings commanded five grand a time, but do they now? No chance; cultural desert out there these days. A few years ago, a top London gallery viewed my work; they said it was technically accomplished, but reactionary – bloody cheek. They wanted cutting edge, like paint, dribbled from the tube or blown from fire extinguishers.

Why are the police after me? Well, a few years ago, fashions changed and my sales slowed. I was in a bit of financial bother and as luck would have it, a dealer asked me to paint something in the style of Cealey. What do you mean, who’s Cealey? Frederic Cealey – the impressionist painter; that’s his portrait on the wall, the one next to Manet’s. Anyway, it didn’t need to be signed; he gave me an advance, so I studied Cealey and his work. The man was a genius; obsessed with light and shadow; liked to paint in the open air; lived most of his life in France. He became my hero. I mixed my paint like him, copied his style and techniques ’till I could produce nearly identical work. The dealer sold the painting and asked for more, all unsigned and perfectly legit; they weren’t copies of Cealey’s, simply works in his style.

After I’d done a dozen or so, he offered me a load of cash to forge an existing Cealey, but I turned that down flat, the risks are enormous but unknown to me at the time, he’d been getting signatures forged on my efforts then selling them as genuine Cealey’s. That’s given me sleepless nights. Trouble is, I think I know who added the signatures and there’s nothing I can do about it. He was a lad I met, not long out of Art College, utterly brilliant, a genius if ever there was. I gave him a bit of encouragement, showed him some tricks of the trade, introduced him around and gave him my gesso formula to prime his canvases. I was short of cash in those days, but he was utterly broke. One day he gave me a bottle of wine, nice one at that. I asked him where he got it. He said one of the dealers I’d introduced him to had paid him a ton of cash to do some small jobs, no questions asked. He hadn’t been married long when his wife had a baby; it had some disability, can’t remember what. With that sort of start in life, he definitely didn’t need the law breathing down his neck, so I kept that to myself, not realising it would come back to haunt me.

Eventually, the Met’s Art and Antiques Squad arrested the dealer. He swore he didn’t say who painted the rogue works, but he must have; I’ve seen cops give me funny looks, and they’ve got plain clothes people after me, no doubt about it. They might not get me for forgery, but they’ll stick conspiracy to defraud on me for sure, which can’t happen, I’m too old to do time. Anyway, that’s all history now; I don’t do impressionists anymore; I can’t be associated with them; it could prove disastrous.

What do you mean, who were the irate customers? Well? …Ok. When the dealer was arrested, his customers realised they’d been conned. There was one in particular who was spitting blood. He couldn’t get at the dealer – he was in jail, so he’s looking for me instead. The police are one thing, but a buyer with an injured wallet is something else, so I keep on the move.

No, copying someone’s style isn’t immoral. Listen, every painting’s a work of art, copy or not. Granted, some are better than others, but what’s immoral is going hungry when so many people have too much of everything. Anyway, there have always been copies, look at Monet, he painted umpteen ‘Haystacks.’ Mark you, I’d be tickled if someone copied my work, means I’ve arrived but I’m glad Cealey isn’t still alive; he was a depressive and lived life in a minor key and was touchy and vindictive.

Although I say it myself, I’ve produced some good stuff but still haven’t made the big time, but it’ll happen, it’s got to; it’s damn well got to. Heaven knows I’ve tried hard enough. I tell you I’ve been so desperate I’ve been to the crossroad at midnight to do a deal with the Man, but he was out, but I’ll do it; with or without him; no doubt about it. Anyway, I’ve got a feeling my current painting’s the one that’s going to make me famous. Ok, I’ve work to do, now back into my imagination you go and breath a word of this and it’ll be the worse for you.

I went to the kitchen and made a sandwich with a bit of cold meat I found and poured a glass of wine from an opened bottle. After pushing the jugs of brushes aside, I eat at the small table by my studio window. The room still smelled of Turps where I’d spilt it last Tuesday.

The women in my life have long gone and my rooms are bachelor pads now. There was a pile of unopened mail on a beat-up sofa. A pine table was heaped with tubes of paint, bottles and old mugs filled with brushes. My apron hung on a nail in the bookcase. Packs of frames and canvases leant against the bureau and there were piles of books everywhere. A bowl of cereals was on a biography of Man Ray, my pipe rack lived on the window sill, empty wine bottles were all over the place, full ones in the First Aid cabinet on the wall. A broken clock was on a shelf beside the radio and near my easel, the waste bin was surrounded by a halo of rubbish. I’m a lousy shot.

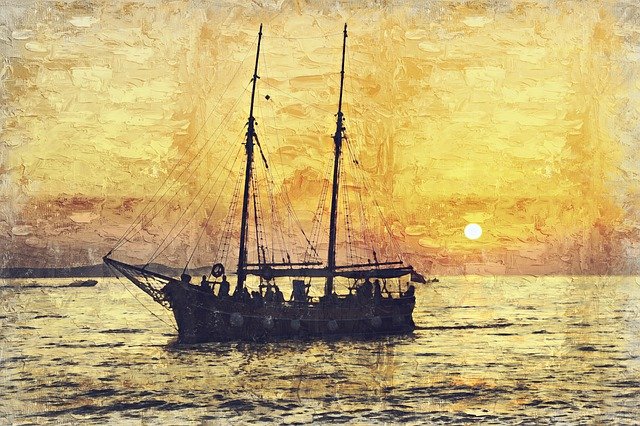

My current painting featured a schooner in a harbour. Why I chose that beats me, the sea gives me the creeps, I can’t swim and how anyone sails for pleasure escapes me. When you’re on the sea you’re a speck in a void and if the waves get you, you disappear as though you never existed. Who needs that?

The sandwich was dreadful so I binned it, filled my pipe and painted and smoked and painted and drank wine until becoming so tired and drunk, I ground to a halt. I inspected the painting; it was coming along nicely so decided to call it a day. As I pulled out plugs and checked locks, I glanced at the portraits on the wall. I swear it; Cealey gave me an evil look. I turned on him, but in a split second, he’d returned to his usual pose. With booze-filled bravado, I squared up to his portrait. “You can pack that up right now! Everyone needs to make a living – you know what it’s like when the plebs won’t buy your stuff, don’t you? It wasn’t personal, just business.” Feeling better after putting him in his place, I got into bed and made a mental note to wash the sheets sometime and tried to sleep, but it was no good; I had to get up and re-check all the locks and windows, you can’t be too careful.

After falling asleep I dreamt that Cealey was wagging his finger at me. I told myself he was dead, but it didn’t stop me from having a nightmare. He chased me as I ran in slow motion through thick water and I couldn’t get away. Eventually, I woke in a sweat with the duvet tangled around my feet, got out of bed, switched the lights on, brewed a cafetière of strong coffee and not finding a clean mug, poured it into a jug and added enough sugar to turn all humanity diabetic.

With my mind befuddled and my head aching, I shuffled to my easel to be greeted with a scene so surreal I dropped the jug. My painting had changed! The colours were now muted and applied impasto, I touched it; the paint was dry. Try as I might, my bewildered mind couldn’t decide if this was reality or if I was still dreaming. I staggered to the kitchen, rinsed the largest mug I could find, filled it with more coffee and kept drinking until my head cleared.

Eventually, I went back to my easel, only to plunge into another nightmare. The painting had changed yet again. “For crying out loud,” 1 screamed, “what the hell’s going on?” My cloudless sky was now overcast, the schooner was now a steamship. I had absolutely no recollection of making the changes. Were the culprits all the empty bottles lying around the studio – for heaven’s sake, how many had I drunk? Even scraping the surface with a pallet knife didn’t work; it barely took the top off which was impossible, the paint had gone too hard for such a short time. I dragged a chair up to the easel, collected the cafetière, baccy and matches with the intention of not moving until I’d figured out what was happening. Having finished my first pipe, I was faced with three alternatives; either I’d been sleepwalking, or someone had broken in or something had happened which was not of this world. I covered myself with the duvet; put the poker beside my chair and willed myself to stay awake to see if I could catch the culprit.

Eventually, morning came. I got up feeling stiff and wobbly, drew the curtains and with great reluctance, inspected the painting. It was unchanged! I’ve rarely been so relieved and to celebrate, decided to tidy the place up. My head was pounding, so swallowed some pain killers then emptied every opened wine bottle into the sink. As I watched the stale liquid swirl down the plughole, the thought occurred that this was lunacy; the stuff cost £7 a go; it would be cheaper to get a couple of crates of beer in. My wallet warmed to that idea, but my creative karma baulked at the alliance of beer and paintings. Maybe it was right. Who could imagine Van Gough painting ‘Sunflowers’ while getting outside a pint of brown ale? I collected the mugs, plates and cutlery, stacked them in the sink; found the sweeping brush and swept the broken jug into a corner then watched mesmerised as dust glittered like diamonds in the sunlight. If I painted that, no one would believe me. Maybe I will someday.

After a shower, I felt somewhat better, so went to make breakfast, only to find the butter was rancid and there was too much mould on the bread.

On checking the cupboards, it was clear I needed to go shopping, so locked my rooms, went to the high street and returned a couple of hours later. Feeling more than a little jittery, I dragged myself to the easel. It was as I’d left it, even the portraits on the wall looked the same. I made lunch and drank the energy drink I’d bought. It looked like fizzy pee and smelled like drain cleaner, then got stuck into putting the painting back as I’d planned it. I made excellent progress but eventually ran out of energy. I was unaware of time and hadn’t noticed it was dark, so cleaned my brushes, checked the locks and windows again and still having the mother of all headaches, swallowed more pain killers and went to bed.

Sunlight shining through the worn curtains woke me the following morning. Holding my breath, I rushed into the studio and to my relief the painting was unchanged. I was famished and decided to have a shower, a good breakfast and finish the confounded thing once and for all. I even shaved my beard off, got dressed and went to boil some eggs, only to find they were a month out of date. I was tempted to take the dratted painting with me, but it was too big, so left it and reluctantly, slipped out to the shops again.

As I returned, I had a premonition something was wrong and as soon as I opened the door, my worst fears were realised. An accordion was playing ‘La Mer’ in the studio. I looked in the mirror and a haggard face with a bloodshot eye stared back at me. Was this what insanity was like? Was I going mad? I picked up the carving knife, crept to the studio door, kicked it open and charged in to find the music was blaring from the radio. I dashed over and ripped the plug from the wall. Then I saw it; my painting had changed dramatically. It was no longer an unfinished, semi-abstract. It was a nearly complete, impressionist study of a ship beside a quay. I wanted to scream at the ridiculous situation, but fortunately, didn’t, it would only have attracted the neighbours. Instead, I went to the bathroom and poured cold water over my head until I’d recovered my self-control.

On leaving the bathroom I passed Cealey’s portrait. I stopped dead. I looked again in disbelief. There was absolutely no doubt about it; he had an evil smirk on his face. That was the last straw. I ripped his portrait off the wall and smashed it over the back of a chair with all the venom I could muster, then threw the mangled frame onto the floor. The broken glass crunched under my feet. Having returned to my painting; the situation had become worse than ever; it had changed yet again. I beat my head with my fists – I must be going mad, there could be no other possible explanation.

Now, people were on the quay, waving; smoke billowed from the funnels and noise and steam seeped into the studio. The painting was both haunting and hypnotic. In front of the vessel were tugs in steam. Then it hit me; my blood ran cold – the painting was pure Cealey through and through. It had his brush strokes, pallet, subtle muted colour and exquisite light on water. It was magnificent, and as I studied it, I was drawn to it and became one with it. Then I saw the signature, large and clear – my signature: Alfred James. I snatched at a knife and scraped and stabbed at the signature, but without the slightest success. I couldn’t even mark the surface so grabbed a tube of Burnt Umber to obliterate the whole thing, but some strange power prevented me from changing a single brush stroke. The studio was now filled with noise, it was surprising the other tenants weren’t complaining. The ship was crowded with excited passengers. I’d given anything to burn the wretched painting there and then, but I was under its spell and powerless. If that wasn’t bad enough, the objects in the painting started to move. The ship blew three blasts on its whistle and the tugs took up the slack from the hawsers. My mind screamed at me; this was only a painting, but somehow my imagination had gone berserk with a twisted plan to drive me mad. Now as my studio walls faded away, I became drawn to the scene itself. Shortly, when all of me was part of the scene and it of me; against my will, I took a step closer, and without realising it, found myself on the aft deck where I was joined by excited passengers from the lower decks.

I was carried with the crowd to the rail and started waiving with everyone else, but to no one in particular. As we got underway, the passengers thinned leaving me all but alone. I was desperately trying to hold on to my sanity. Was this a hallucination? I searched through my pockets, found my penknife and jabbed it into my forearm. The pain was real and so was the trickle of blood. I clutched my arm and turned, just as two young ladies walked towards me, arm in arm.

“Excuse me, ladies, what vessel is this we sail on?” I asked, trying to stay calm. They giggled.

“Oh, Lizzie, what a hoot! I think we’ve got a stowaway. Can’t wait to tell the others; they’ll never believe this fellow doesn’t know he’s on the Titanic.”

THE END

Copyright Tony Billinghurst 2021