And Some Will be Gray by Chere Taylor

And Some Will be Gray by Chere Taylor

My father was a son-of-a-bitch before it ever became popular to be one. Later in life, he would be celebrated for that very trait. Admired for his projection of strength and masculinity. In 1871, he would be elected mayor of our small town, Prairie Haven, located in the newly minted region known as the Arizona Territory. He would rule that town the same way he dominated his first son, me, and the wife who died while giving birth to me. Unyielding, unbending. You did what James Garrett told you to do with a ‘Yes sir’ or otherwise risk a ‘Slug to the throat!’

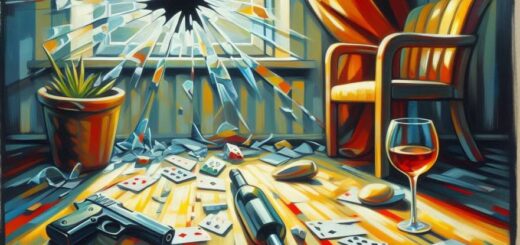

That’s what he called it, when he slaughtered the cow thief or perhaps just some drunken bastard who mistook our cattle ranch for his own domicile. I always pictured him in my head stumbling his way around our livestock, perhaps tipping his derby to the sleeping bulls.

“That son-of-a-bitch earned himself a slug to the throat!” James proclaimed while straddling the dead man’s body. Pa was a big man with burly, black hair and a beard. He gripped his pistol, adopting the same authority and reverence of a preacher man clinging to his cross.

I remember my nine-year-old self examining the corpse along with my older brother Gabriel. There were no ‘slugs’ in the dead man’s throat, though his head had caved in from the force of the single shot bullet. It reminded me of the time I accidentally rode our horse through Missus Neely’s garden, smashing half of the melons with the horse’s hooves.

This is death. I told myself. This is what it looks like. I tried to soak it up. To make it real to myself.

From that point on, I made it my life’s work to make sure Papa loved me enough so I wouldn’t earn “ …a slug to the throat.”. I didn’t, couldn’t, love him in return. How could I love a man who choked my eleven-year-old brother til he fell unconscious to the floor? Or the time he stood guard on the front porch refusing to allow me back into the house, even though it was after two in the morning until I had cleared enough snow for our oxen to eat. The gun had been there too, almost as a separate entity, casually resting in my father’s lap.

It was that same pistol he placed in my sixteen-year-old hands years later. The war was over and Gabriel was due back home any day now.

“Shoot any gray,” Pa told me, “that steps foot in our yard.” I could smell the liquor on his breath. Something vile and harsh and mysteriously adult like.

“What if it’s —“

“Shoot the grays I said! There will be no wickedness staining this here soil. You understand me, boy?”

I swallowed the rest of my unfinished question. What if it’s Gabriel?

Perhaps Pa detected my silent thought. He put one hand on the back of my neck, a reassuring gesture if it wasn’t for the calluses on his palm, the pressure of those massaging fingers.

“It don’t matter who’s wearing the coat. Even if it’s kin, you shoot him dead. The grays betrayed our country. So you give any gray you see a slug to the throat, or so help me, I’ll be giving you one.”

I nodded even though I understood that Gabriel’s true crime was not so much that he betrayed our country, but that he betrayed our father, which, as for as Papa was concerned, was far worse.

Gabriel made a child with one of Samuel’s (a visiting relative) slaves. Not a sin in itself. The female slaves gave birth to lots of mulatto children. But Gabriel didn’t have the good sense to be quiet about it. He bragged about his fatherhood to us and the townsfolk. He even tried to buy the kid from Samuel, if the rumors were correct. All of Prairie Haven turned against him at that point. I guess he thought that by joining the Southern cause, he would reinstate his status as a white man. Again, wrong move.

So every morning that April, instead of helping the farm hands with mending the fences or feeding livestock, I took the long walk to East-wind Trail, which was about a hundred yards from our home. There I waited for Gabriel or any gray’s return until the sun dipped beneath the horizon again. Of course, I wasn’t going to shoot him or anybody else. Just give a warning shot in the air. One bullet and one shot. Then I would run behind the back of the house, pick up my already packed luggage and continue on East-wind Trail to join the ranks of carpetbaggers, never to return to Prairie Haven again.

Each day, to my great relief, there were no grays. I saw plenty of horse-drawn carriages. Travel had certainly picked up after the war. Occasionally, men in blue coats would also appear, though I didn’t recognize anyone.

Maybe he’s dead, I thought as I traced an endless pattern of circles on the dusty road beneath my shoe. I pictured Gabriel lying in some unmarked field, his body bloodstained with a bashed-in head where his thinking used to be. Yet even then there was something to be admired there. He had escaped Papa.

It was one fine morning when I stepped out on our front porch after breakfast. There in the distance, a wink of gray. It was hard to be sure of the exact color of the silhouette behind the strength of the rising sun, but it was making its way towards our home.

My heart dropped to my belly. No, no, no, it couldn’t be him! I raced towards the dirt road, cutting across the wheat fields, the single shot pistol banging against by my side. All Confederate Soldiers were ordered to return their coats as part of their surrender agreement, I reminded myself. That’s what it said in the Weekly Arizonan. There will be no grays here!

As I got closer to the limping figure, it was no longer possible to deny the obvious. Gabriel was coming home …and in a gray coat. Slowly, he hobbled on his crutches, now only several feet away from me. I saw a shock of red hair peeking out from the gray cap, his face worn and dirty. This was not the confident, devil-may-care Gabriel who left for war, but a soul who had been beaten up, spat upon and then inserted back into Gabriel’s body. What would his reaction be, after he watches his only brother shoot a bullet into the air at his approach?

“Whacha’ doing lil’ brother?” He favored me with such a warm and innocent smile, it broke my heart. “God, you grew up so much since I’ve been gone. You’re almost as tall as I am now. Has it really been three years?”

That’s when the idea hit me like a lightning bolt. An idea so brilliant, it almost blinded me with its perfection.

“Take off your coat and leave it by the side of the road.”

His smile fell, allowing more of his weariness to bleed through. “That’s all I get? Not even a ‘hello’?”

“Papa told me to kill you.” I hissed and looked back towards our home. It was so far away that I couldn’t tell if anyone was standing on the front porch. But something twinkled in the distance, a flash of light. Perhaps the glint from a whiskey bottle.

“But I don’t have to do it, if you’re not wearing a confederate uniform. That’s the only thing he’s pissed about. Drop the coat.”

“And go home naked? Ashamed? No thanks.” Gabriel shook his head. “I knew it was a mistake coming back. Papa never forgives nuthin’. Should have just gone and left with Jo-Jo.” Jo-Jo was Gabriel’s bastard, colored son. Suddenly his eyebrows rose, as if he had been struck with his own lightning moment. “Why don’t you come with me, and we’ll skip Prairie Haven for good? I’m tired of the ‘good folks’ around here, anyway.”

But I was lit with my own wit at that point. To outsmart Pa? To defeat him with his own damnable logic? That doesn’t happen often, but it always felt good when it did.

“You could wear my shirt.” This was even better because it happened to be a plaid blue. “Put it on and we’ll both tell him goodbye together. Then hell, I’ll go with you.”

Gabriel’s eyes flitted here and there as if searching for another answer that was buried in the wheat fields. Then wearily, he nodded and we began the process of undressing.

I hunched over as I unbuttoned my shirt, embarrassed of my thin, skeletal chest, its unhealthy, pale color like the underside of a fish. When would I develop the muscles that both Gabriel and Pa had? Then Gabriel removed his coat and my breath hitched in my throat.

On his left side was a large, gaping wound, about the size of my fist. It was raw and angry looking. It didn’t seem like a man who had a wound that size, would still be walking in the land of the living.

“A Yankee got me.” Gabriel replied when he saw me staring at it. “Doctor said it was best to let it drain before he bandages it up.”

Next he removed his pants, revealing the signs of another angry wound in the process. At least this one was properly bandaged up, even if the cloth was stained red in some areas. At last, he removed his cap and carefully placed it alongside his other garments by the roadside.

I gave him my blue shirt but didn’t bother giving him my pants. It was doubtful he could fit into it anyway with his wounded leg.

We limped our way back through the yellow field, moving clumsily through its waves, like a wounded elephant. All the while I kept thinking about the Pa’s cow thief, who was in reality most likely a drunken neighbor. Was his shambling similar to ours?

Pa was indeed sitting in the rocking chair. An empty bottle of Old Crow rested on his lap, his face emotionless. I didn’t like his bland expression. I would have preferred if he were wearing a scowl. Anger was an emotion I was familiar with. Not this empty facade.

“It’s Gabe, Pa. Gabe’s come home. But he ain’t wearing the gray, see? So, I didn’t shoot him. He wants me to go up north with him.”

I hated how my voice sounded. Weak. Like I was asking for permission instead of telling him what I was going to do.

His gaze shifted from me to Gabriel. Without giving me another glance, Pa reached behind his back, took out a second pistol and put a bullet in me.

To be fair, it wasn’t a slug to the throat. Pa wanted to be more sure than that. He aimed directly for my face. I was dead, my head a smashed open melon before my body even sunk to the ground.

Gabriel’s hair would be his excuse. There were two small patches of gray on both sides of his temples. Not enough for someone who helped carry his brother across a field of yellow to notice. But enough for a fanatical son-of-a-bitch who punished his sons to make up for his fucked up life to take note of. Who expects gray hair on a nineteen-year-old? But war has a way of changing people, contorting them into unfamiliar shapes.

Pa never shot Gabriel. Perhaps the fear in Gabriel’s eyes was enough to momentarily satisfy him. The very next day, Gabriel escaped to the east, stealing his bastard son in the process. The colored woman was terribly upset about it, but the Negroes had no rights yet. There was nothing she could do other than weep and wail, her tears staining her printed copy of the Emancipation Proclamation.

After Pa become the mayor a few years later, he remarried. The corpses he had left in his wake made no difference in his electoral status or in matters of romance. He created more children, and they too learned how to tiptoe around his whimsical fury. How to carry the individual pieces of his liquored up life.

And that should have been the end of it. Except even in death I continue, as will Gabriel Garret and James William Garret when we meet again in the next life.

* * * * THE END * * * *

Copyright Chere Taylor 2024

I was absolutely absorbed by this haunting tale “Some Will Be Gray”. It is was awesome in its gruesoness and evil beyond words. I looked for redemption between the lines, being somewhat assured at the end that redemotion will come. FASINATING!

Chere, you’ve done it again. For some reason, I thought maybe Pa would have had a change of heart when he saw Gabriel. Guess I was wrong. It makes my heart hurt when bad people continue to do bad things. I like good endings.

Wonderful story, Chere! It could have been titled, “Some Will Be Sonsofbitches.” It epitomizes the remorseless, pitiless amongst us. Great tale!