More Than Me by Bill Tope

More Than Me by Bill Tope

1

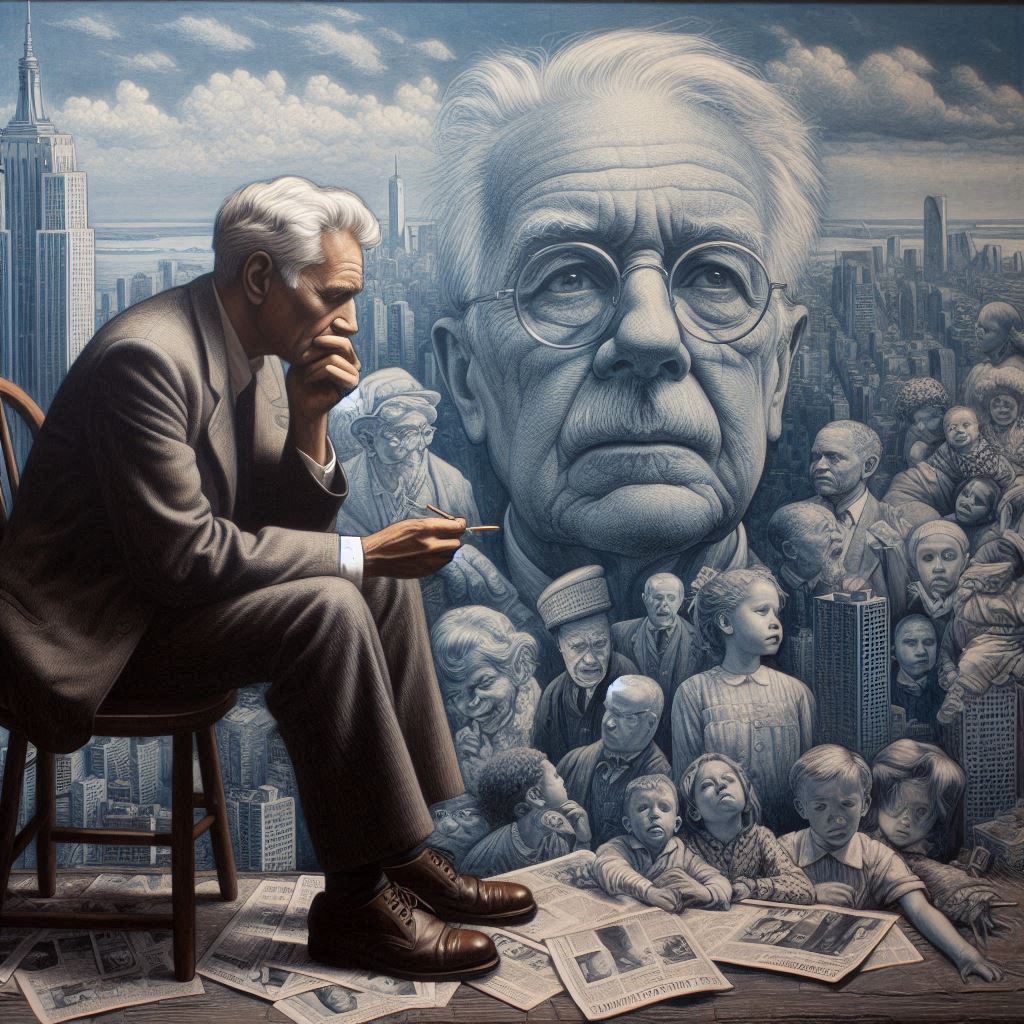

Henry glanced down at himself, saw the threadbare white t-shirt with the food stains and where he’d brushed his teeth that morning and dribbled toothpaste onto the fabric. He spied a stray cornflake from the breakfast he’d choked down, and brushed it away like an errant moth. He frowned. He hadn’t realized he’d slipped that far into the shadows, into oblivion.

Henry recalled decades earlier, when in the flower of his youth he’d spied aged men sitting on the green-painted benches in the park — much like the one on which he sat this afternoon — silently and motionlessly fading away. He’d wondered, who or what had left these forgotten souls so bereft? Hadn’t they any family, any friends, any keepers?

Now Henry sat alone on the park bench. He had no family, no friends. No keepers. Aging was not as easy as he’d thought it would be. With nothing to occupy their time or thoughts, people lapsed into dissolution. Henry was, he realized, an old man. It struck him hard, like a clenched fist.

Henry wasn’t impoverished, despite appearances. He had, as the actuaries at his old firm like to say, accrued a substantial estate. He’d toiled hard all his working life, set on achieving all he could in the way of material gain and political power. But, to what end? he wondered now. He had no heirs. His wives and children had predeceased him, abandoning him to an emotional chaos for which he never forgave them. Why had he worked so hard to be a provider when there were no remaining beneficiaries? There: he sounded now like the estate lawyer he’d once been. He smiled briefly, like a flickering candle, and then his face turned blank again.

2

“I love you, Beegie,” said Henry, stroking his new wife’s slender hips.

“Maybe I should go by Barbara from now on,” she suggested. “Whoever heard of a lawyer’s wife being called Beegie? It doesn’t sound serious. It might hurt your career,” she suggested.

“Don’t care, Mrs. Schafer,” replied Henry. They were on their honeymoon, following a modest civil ceremony at the courthouse that afternoon.

She sighed. “So, let’s get down to brass tacks, Mister,” she went on. “How many children do you want?”

Henry blinked. “Do I have to decide now?” he asked with amusement.

“It’s good to anticipate the future,” cautioned Beegie. “That way, there are no surprises.”

“Maybe I like surprises,” said Henry.

“We need at least two sons,” said Beegie. “An heir and a spare,” she said very seriously.

Henry laughed. “We’re not the British Royal Family, darling. And why do they have to be sons?”

“You’ll want them to follow in your footsteps and become attorneys,” asserted his wife.

“Why can’t daughters become attorneys?” asked Henry.

“Women make up what, one percent of practicing attorneys in New York City?” Beegie pointed out.

“And who said they have to be lawyers?” asked Henry. “Maybe they’ll want to become school teachers or nurses — or doctors!” he cried. Henry had attended a venerable Eastern law school and was bursting with liberal ideals that were emblematic of the1960s.

Beegie blushed. “Oh, stop it. There are even fewer women doctors than attorneys, as if you didn’t know.”

“Sweetheart,” said Henry, “I don’t care what our children turn out to be, so long as they’re healthy.” She held him close, deeply in love.

& & &

But the first Schafer child turned out not to be healthy. Darla was born with a shortened limb and would always walk with a limp, the doctors said. Beegie was not happy. She felt like she had let her growing family down.

“How can Darla argue a case before a jury when she’s leaning on a cane?” she lamented, near to tears with dismay.

“Baby,” said Henry, “Darla needn’t even be a lawyer. She can be a businesswoman or a news reporter, or she can hang wallpaper, for Chrissake. Dammit, she’s my daughter, and she’s perfect!”

Beegie held her husband close. “Yes dear,” she said.

Darla died in her crib, aged 3 months.

Almost two years later, Beegie’s womb bore fruit a second time. Angela was the apple of the Schafers’ eye. With raven hair and a pink complexion, she was, her parents agreed, utterly perfect.

“Beegie,” said Henry with love, “you did good!” Beegie squealed with delight. Any guilt she felt over the tragedy of her previous childbirth was more than atoned for by the arrival of her beautiful daughter Angie. So it was with profound disappointment and heartbreak that the Schafers’ daughter of 9 months quietly passed away in her sleep, another victim of crib death. Henry was beside himself with grief.

& & &

The untimely passing of Beegie and Henry’s children served at first to bring the couple even closer. They cherished each moment together, as if it were a gift from God. Life, they felt, was just that precious. They deferred having more children until October of 1969 when Beegie approached her husband and tentatively told him that he was to be a father once again. While Beegie had anticipated that Henry might have misgivings, he was anything but dismayed.

“Baby,” he said, “I’m so happy!” And they kissed.

But, the child experienced congenital respiratory distress, so severe that Henry and Beegie both quit smoking. And Phil was a premie. However, Henry, now entertaining an offer to become a junior partner, could afford a full-time nurse, and Phil made great strides toward a complete recovery.

“Maddie,” Henry addressed the nurse, “the only thing that matters is my son’s well being.”

“I understand, Mr. Schafer,” she said.

And Henry and Beegie’s first son did prosper. Henry, now a partner, maintained Maddie’s employment for almost five years, far longer than Henry’s similarly prosperous colleagues did. But, Henry told himself, there had been no nursemaid or governess with the first two children, and they had suffered keenly for it. Maddie wasn’t let go until Phil began school. Henry had begun to have grave doubts about Beegie’s fitness as a parent.

Henry had read a recent book of nonfiction about a woman who systematically murdered her children, owing to a psychosis of some sort. Henry was no psychologist, but he subconsciously fitted his wife of 7 years into that very category of infanticidal sociopath. Henry was careful to tell Maddie to let no one, outside of himself, be left alone with his son. At about this time, Henry began devoting more time than ever to his career, and to become involved in conservative causes, both professionally and otherwise. Less empathetic now, he became emotionally distanced from his wife and sought out company elsewhere. Beegie began to drink.

“Maddie wouldn’t let me take Phil to the park,” complained Beegie one day, slurring her words a little.

Good! thought Henry. “What did she say about it?” he asked aloud.

“She said the doctor said he had some kind of ‘itis’ and advised against visiting the park,” replied Beegie. “I don’t recall any such diagnosis,” she said unhappily.

“Oh, I do,” said Henry. Beegie shrugged and frowned and said nothing more. She poured herself a bourbon.

3

Henry and Beegie’s relationship became more and more remote, until which point they hardly touched one another in affection. They began sleeping in separate bedrooms. One night, however, after marking their 15th wedding anniversary, a celebration accented with the consumption of a magnum of champagne. the couple wound up in the same bed. 12 weeks later, Beegie returned from the OB-GYN with news.

“I’m pregnant, Henry,” she announced with dead, listless eyes.

Henry didn’t know quite what to say, so he said the first thing that popped carelessly into his head: “Is it mine?” he asked.

Phil, ten years old, greeted the arrival of a baby brother with great fanfare.

“What are we gonna name him, Dad?” he asked.

Henry, having secretly determined by way of blood tests that the child could well be his own, had come to accept it. He shrugged at his son’s question.

“We’ll name him Harry, after your father,” declared Beegie determinedly.

Harry Schafer came into the world on New Year’s Day, 1980, and was the first child born in the city hospital that year. He thus received his first of many rave reviews.

No further anniversary celebrations, and so no more children, were forthcoming. The Schafers, man and wife, grew even more distant. Henry spent many nights “working late.” But, that fate was not ordained for the couple’s children: they prospered from love and devotion, both from their parents and from one another. Man and wife found little to discuss, but for their sons.

& & &

Trying desperately to find some basis for a reconciliation, Beegie asked Henry one Sunday, as she had many times before, “Do you want to attend mass with me this morning?”

Henry grimaced. “You know I don’t fancy that shit, Beegie,” he answered, annoyed with the question.

“But, you appear on Jesus Lives every week,” she said, mentioning an Evangelical Christian television program from which Henry received a substantial retainer. “What’s that all about?”

“That’s work, Beegie,” he remarked gruffly, tying his necktie. “I perform a service and I take their dough; it’s business, that’s all.”

“But,” she said, “what do you really think of the organization?”

“Same as all religions. Bunch of damn holy rollers,” he said dismissively. “I’ve got an appointment,” he muttered, and swiftly vacated the apartment.

An appointment? Beegie thought. At 7am on a Sunday? She knew damn well who it was with. She worried her rosary beads.

& & &

“What happened to your face, Harry?” asked Phil one afternoon.

“Kid called me queer,” said 7-year-old Harry resentfully, dabbing with a tissue at a split lip.

“Why’d he do that?” asked Phil.

Harry was silent for a moment, then replied, “Because he saw me holding hands with another kid — another boy.” Phil, now 17 and wise beyond his years, said nothing. “Does that mean I’m queer?” Harry asked his brother. Phil, he knew, had never lied to him. In fact, Phil was a defacto father figure to Harry. Henry, increasingly preoccupied, played a diminishing role in raising his younger son.

“Doesn’t matter what it makes you,” answered Phil. “It’s who you are. You’re my brother, Harry. I love you and I don’t care what you are or who you hold hands with. Okay?”

“Okay.”

& & &

Henry marched into Harry’s room and snatched a spinning platter off his12-year-old son’s vintage turntable. He smashed the album into bits on the side of the machine.

“No more of this goddamn fairy music, Harry!” shouted Henry angrily. He had been hired as lead counsel for another alt-right organization dedicated to forestalling legislation allowing for same-sex marriage. This was the hot button issue facing both sides of the gay rights movement. His son’s “oddness” would only garner criticism and reflect badly on Henry.

“I love Queen!” Harry shouted back. “Freddy Mercury is the best singer, if you don’t count George Michael.”

“What’ve you got against Springsteen?” asked Henry in a surly voice.

“Nothing! He’s just not Freddy Mercury!”

“That faggot died of AIDS!” said Henry harshly. “Is that what you want for your future?”

“Is that why you don’t love me, Dad?” asked Harry petulantly, “because I’m queer?”

“You’re not!” snapped his father. Henry saw red every time such a suggestion was made. “Either you straighten out or I’ll put an end to this music thing you’re into. I got you your guitars and the lessons and the keyboard and everything. You don’t want to lose that, do you?”

Harry grew pensive and seemed to turn this over in his mind. At length, he sighed and gave the pragmatic response he father expected. “Okay, Dad. No more Queen.” As Henry stalked triumphantly from the room, Harry stared balefully at his father’s departing back.

& &&

“Phil is starting the conference championship game on Saturday,” said Henry with a smug smile, referencing his son’s acclaimed ability to accurately toss a football 50 yards down the field to a wide receiver. Last year, Phil had been selected Division I Second Team All-American for his football prowess at the medium-sized college he attended. He was foregoing the NFL draft to enroll in a prestigious law school and would thereby follow in Henry’s footsteps. Phil was all man, thought Henry proudly.

“I’ve already got tickets,” said Beegie, looking up. Are you going with Harry and me?” she asked hopefully. “Or are you…”

He shook his head. “I’ll catch a ride with Carol,” he replied, referencing his long-time paralegal from the firm. Beegie said nothing.

When it was Harry’s moment to shine, he did so in other ways. He attended Julliard, majoring in voice, for two years, before dropping out to become frontman and lead guitarist for his grunge rock band. He filled bars, auditoriums, arenas and, eventually, stadiums. One night, Henry paid an unexpected — and unprecedented — visit to Harry backstage at a concert venue. What he discovered there left him positively jubilant.

“Who’s this, Harry?” asked his father, nodding at a stunning African American woman standing in Harry’s dressing room.

“This is Toni,” said Harry. “Toni, this is my dad, Henry Schafer.”

“Ooh, hello, Mr. Schafer,” cooed Toni, extending her hand. “I’ve seen you on television.” After hesitating for just a beat, Henry enfolded her slender fingers with his own. The three engaged in meaningless small talk for a few minutes before Henry took his leave, satisfaction written all over his face. He had gotten what he came for.

“I’ll leave you now, Harry,” said Dad, smirking. “I can see you’re in good hands.”

When Henry had left, Toni turned to Harry and said, “Your Dad seems nice.” Harry merely stared at the door through which his father had passed.

That night, Henry told Beegie, “I think maybe Harry is finally coming around.” Beegie glanced at him inquiringly. “Had this hot chick in his dressing room before the concert,” he went on. “I think he was going to make her.”

“What was she like?” asked Beegie.

“Black,” said Henry distastefully. “Toni something, but she had a nice ass.” Beegie, who knew Toni and many of Harry’s other friends, didn’t have the heart to tell her husband that Toni was in fact a transgender woman.

Harry became a rock and roll phenom, filling in the minds of many the role left vacant by the death of Freddy Mercury 3 years before. So, when Harry died of a heroin overdose at 24, the music world was beside itself. But no more so than his family. His mother’s reaction was to drink more, while his father’s response was to devote more energy to the alt-right causes which had become so paramount in his life.

Phil, now 35, felt Harry’s loss more acutely than anyone. Now a partner in the law firm that Henry had retired from only the year before, he sought but gleaned little comfort from his parents. He tried to talk to them, but found it almost impossible. He came upon them in their living room, a few days following the funeral.

“Mom, Dad,” he said, “I’m thinking of creating a foundation in Harry’s name.” He looked at them, sprawled over the sofa, but their faces remained turned away. “I’d like your input: what form should it take? How should I fund it? Who should be the beneficiaries? I’m thinking of scholarships to Julliard.” No response. “Do you even think it’s a good idea?” he implored. Still nothing.

“Fine,” he muttered, turning away and exiting the room. “Thanks for the advice.”

4

Ten years had passed since his brother’s death, and Phil, now managing partner of the firm, was an outspoken LGBTQ rights activist. Married and with a gender dysphoric teenager of his own, Phil was often questioned on the reasons behind his speaking out on behalf of the non-cisgender community.

“I believe in equal participation in society by all people, regardless of their sex, gender identity, race, ableness…” was his stock answer.

One day, he spoke of his late brother. Asked point blank whether Harry Schafer, as had been rumored for years, was LGBTQ, Phil replied, “It’s true, he was. He suffered in isolation, in agony, in loneliness, for 24 years, and I’m speaking out and speaking up for him and everyone like him, because,” he said simply, “it’s the right thing to do.”

“I don’t know what the hell’s the matter with that boy,” lamented Henry that morning, after seeing his son address the press conference on an initiatve to legally validate same-sex marriages at the state level. Moreover, Phil had officially outted Henry’s younger son.

“He’s not a boy, he’s a man,” retorted Beegie, who had been viewing the same news program. “Why don’t you give him his due, Henry? He’s right about LGBTQ people, and he’s right about Harry.”

“My son was not gay!” he spat, slamming down a newspaper and laying heavy emphasis on the last word.

“He was,” she intoned relentlessly. “He was so intimidated by you and your macho persona and your radical causes that he hid it, except from me and Phil and a few friends. He tried talking to you.”

“Harry always was weak,” he snarled, aiming a venomous glare his wife’s way. “If he was gay, then you made him that way!” Henry snapped viciously. Beegie rolled her eyes.

“Why do you think he took his own life, Henry?” she challenged.

“He didn’t! It was an overdose. It was accidental!” shouted Henry.

“You are so fucking blind,” she said with disgust. “He wanted to talk to you, to explain why he was the way that he was, since he was 12 years old, but you’d never hear of it. It was always, ‘Did you score with this chick, did you make it with that bitch?’ ” Henry stared at her. “Do you remember the time you bought him the DVD and all those porn discs and told him to sit in his room and watch them until he felt like a man? He was 13 freaking years old, Henry,” she cried with despair, her voice breaking. “But then,” she continued more softly, “I bought himThelma and Louise, so he could watch Brad Pitt.” She laughed sadly, remembering.

“Oh, have another drink,” he said dismissively, and Henry stormed out of the condo, slamming the door and leaving his wife by herself once more.

5

Phil Schafer’s final words were broadcast six months later, on a Sunday morning public affairs program with a nationwide viewership. He was discussing his storied career as an outspoken advocate for the LGBTQ community, of which his beloved brother had been a part. Since confirming his brother’s sexual identity, Phil had received many death threats, some from the same organizations which were represented by his father. The two men hadn’t spoken in months. Phil’s appearance was in conjunction with a recent Supreme Court decision to sanction same-sex marriage. When asked to what Phil attributed his tireless commitment to serving the under-privileged, the downtrodden and the marginalized, he replied cryptically that “I owe everything I am to my father.”

Seven hours after air time, Phil Schafer was found dead in a men’s room in Union Station, with a gunshot wound to the brain. His wallet, containing $400, was untouched. The perpetrator was never found. Henry, who was in Oslo, where he was receiving the latest in a score of honorary law degrees, was asked for his reaction.

“Naturally,” said Henry, “I am shocked and dismayed. My son didn’t live the life I’d hoped for, but of course, I loved him. My thoughts are with his mother and his wife.” Unmentioned was Phil’s 19-year-old transgender son, whom Henry hadn’t seen in so long that he wouldn’t have recognized him on the street. Henry then excused himself for a golf date he’d previously scheduled.

Beegie, unable to cope with the tragic news, sat alone in the Schafers’ condo for months and binged on chocolate and bourbon. Grown over the years to a bloated 300 pounds, she eventually collapsed with a stroke and spent the next 14 months hospitalized, in a coma, before finally passing away in her sleep at age 66.

6

Following his wife’s death nearly 10 years before, Henry became increasingly reclusive and unresponsive to the efforts of others to get him to connect with society. When asked by reporters what he thought, as a cultural warrior, or as an elder statesman of note, of this or that, he would curtly reply, “Don’t know, don’t care,” and he’d slam up the telephone. As a long-time spokesperson for the anti-abortion and anti-LGBTQ and anti-DEI movements, he would address the issues only fleetingly, speaking of the “recidivism of the Negro,” and touting the Supreme Court’s decision in the Dobbs case. And he reiterated that his favorite Supreme Court justice was Roger Taney, followed closely by Clarence Thomas.

At length, one of the Big Five New York publishing houses tried to entice Henry Schafer into penning a much sought-after, agenda-driven autobiography, but he wouldn’t bite. At 80, Henry unexpectedly wed his long-time personal assistant, Carol Moseby, his unacknowledged mistress of forty years. But, tragedy was visited on Schafer once more when Carol died in their honeymoon suite on their wedding night. Foul play was not suspected. Two days later, Henry played in a foursome at Pebble Beach.

& & &

Still seated on the bench, Henry thought indifferently back to when he’d last seen his first wife — or her desiccated remains — vegetating in the so-called recovery center that cost him $1,000 a day. He sniffed. He could well afford it. He couldn’t remember now the last time they’d made love. Beegie had died from a massive hemorrhagic stroke, the doctors had said, an indirect result of her long-term alcoholism and malnutrition. He shook his head in disgust. The medical examiner never had discovered what caused Carol’s death, he remembered with a little smile. At any rate, there would be no tell-all book now. He glanced at his cell. Time to get home, he thought. Henry phoned up his driver and told him to bring the car around.

Henry tried to stand up, but he fell back hard onto the wooden bench. His head swam; he felt lightheaded and confused. He slumped and didn’t move when Edward, his driver, arrived and touched him on the shoulder. Henry remained unresponsive, so Edward punched in 911. In seeming no time, the ambulance rolled into the park with the lights flashing and the siren blaring. Alighting from the vehicle, two paramedics rushed to Henry’s side and immediately began working on him. They were very professional. A small crowd of the curious gathered around the scene.

Working their first responder magic, the EMTs soon had their patient breathing regularly again and his heartbeat restored to somewhat normal. Henry was aware of what unfolded around him, but he couldn’t speak. He had a terrific headache.

“Patient locked in,” said one of the EMTs into her radio, which squawked back with a burst of chatter. “Roger that,” she said. As they placed Henry on a collapsible gurney, they secured him with wide leather straps, fitted him with an oxygen mask and one of the first responders talked to him. He found her soft voice very calming and reassuring.

What if he were to die? thought Henry bleakly. He knew, intellectually, that some day he must pass from the earth, but had given little thought to what came after. His wife had been Catholic and Beegie raised the boys in the faith, but Henry had never spent much time in an actual church, other than for an ill-advised reinactment of his wedding on his 20th anniversary. Beegie had adamantly refused his overtures of divorce, for religious reasons, but in the end it didn’t matter; he had enjoyed his freedom just the same.

They folded the gurney into the ambulance and off they streaked. “I think you’re gonna make it, Mr. Schafer,” said one of the first responders happily. The one with the nice voice. He turned his head to look at her. What he saw gave him pause. She was a 20-something Black women, in a navy blue uniform, on the collar of which was affixed a colorful rainbow pin. Suddenly the woman with the nice voice spoke again, but in a deep, masculine voice.

“Funny you should get the likes of us, huh, Mr. Schafer?” And she laughed aloud. The laughter seemed to swell and then echo through the vehicle. Henry thought he smelled burning sulfur.

As the ambulance raced to the hospital, Henry wondered, not for the last time, if he were already dead, and in hell. Or was it heaven? Did it even matter?

* * * * THE END * * * *

Copyright Bill Tope 2024