Two Brothers by Bill Tope

Two Brothers by Bill Tope

1984

It was well past midnight when Dad padded from his bedroom out to the living room of the small frame house in Southern Illinois. He had been awakened by a din emanating from the stereo and the voices of a score of persons unknown to him, who were packed into the living room and kitchen. The air was thick with cigarette smoke as well as the sweet effluvium of marijuana. A high-pitched soprano soared above the rumble of voices and shrilled the length of the house. A flutter of laughter followed. Dad frowned. As he stepped into the room, no one seemed to pay him any mind. Finding his son, he gestured to him. Joey staggered to his father, grinning stupidly.

“What the hell is going on, Joey?” asked Dad. Joey shook his head as if to clear it, then proferred a lighted joint. He had a shit-eating grin on his face.

“Take a hit, Dad,” he urged in a sing-song voice. “It’ll get you high, man!”

Dad waved the offer away and his face, if possible, grew even darker. Now he knew where the five hundred dollars he had gifted his son had gone. The room was rife with drugs and alcohol. A girl with long blond hair, who couldn’t have been more than fifteen, floated by, as if in a daze. Dad shook his head disapprovingly.

“I opened up my home to you,” he rumbled angrily. “And you bring all this shit into it.”

Joey blinked. He was having trouble following his father’s words. Dad continued, “Now, take your friends and your drugs, and get the hell out. This isn’t your home anymore. Get out,” he repeated. “And,” he added meaningfully, “don’t come back.”

Instantly sobered by this harsh rejection, Joey frowned, quickly gathered the partyers, and steered everyone to the door. “Let’s go over to Mike’s house,” he said, referencing his best friend, a skinny blond man in a biker vest. And, leaving an unmerciful mess behind them, the entourage quitted the Schafer house. As they left, Mom crept from the bed and joined her husband in the living room. The door slammed shut. A thick blue fog of pot smoke hovered near the ceiling and overflowing ashtrays and spilled bottles of beer littered the residence. Sitting on the arm of a recliner was a hypodermic syringe.

“I’m sorry, Pete,” she said, as though it were her fault.

“It’s alright ‘hon. We’ve still got one son.”

& & &

Eight Days Before

The telephone rang at Jeff’s house, which was located out in the country, in a rustic suburb of St. Louis. It was Mom.

“Joey’s home,” she said breathlessly. She waited a beat. Jeff said nothing.

“Jeff,” she said. “Are you there?”

“I’m here.”

“Are you going to come and see your brother, visit for a while?” she asked hopefully. Jeff thought back to how Joey hadn’t touched base with any member of his family for seven long years. That was a lot of unanswered letters, a lot of unreturned phone calls, a never-ending questioning of Joey’s many friends.

“No, Mom, I’ll pass. I’m sort of busy, you know.”

After a pause, his mom said, “I understand.”

“How long will Joey be there?” Jeff asked.

“He’s going back to California in a week,” she replied.

“See you in eight days, then, Mom.”

“Bye, honey,” she said sadly.

“Bye, Mom.”

& & &

Seated at the dinner table, Jeff looked up from the hamburger casserole and asked, “How was the visit with Joey?”

Mom lowered her head, appeared ready to cry. He glanced at Dad, who as usual was stoic and unreadable.

“You don’t seem very happy about seeing him again,” observed Jeff thoughtfully. Mom was forever conjecturing about Joey’s whereabouts, about how she was dying to see him again. Nobody said anything. It wasn’t until months later that the true story of Joey’s visit was given to Jeff. It was worse than he had imagined. Moreover, it helped explained the dark, brooding stain on Dad’s recliner, the only decent piece of furniture in the Schafer home.

& & &

The Phone Call

The phone rang in the living room and Mom answered it. When she heard the voice at the other end of the line, she gasped and held her breath. It was Joey, her oldest son, and he was crying. Joey was 37 years old, and he hadn’t cried since he was a small child, when a cherry bomb had exploded prematurely in his hand.

“I don’t have any money, Mom,” he said, his voice breaking. “I haven’t eaten in two days. It’s cold in San Francisco. I was sleeping in a shelter but they kicked me out…” And so on. Stricken, Mom put Dad on the line and he talked with unusual gentleness to his first-born. It was decided that Joey, who hadn’t shown his face for seven years–neither a call nor a card nor a word from anyone who knew him–would be wired funds for bus passage — the Schafers couldn’t afford an airline ticket — and he would proceed home to recover from his ordeal. Back to the home fires, and everything would be good. Mom and Dad waited eagerly.

The reunion was joyous and heartfelt. The prodigal son had returned and he was welcomed back and embraced with love and warmth.

“Joey,” murmured Mom, touching his narrow shoulders, “you’re so thin.” Her eyes glazed over with tears. “We’ll put some meat on your bones,” she vowed.

While Joey was in the bathroom, Dad told Mom, “I’m going to give him five hundred dollars. That way,” he explained, “he can get some new clothes and you know, feel good about himself again.” The Schafers knew poverty well, having lived through the Great Depression. Mom readily agreed. Of course, the Schafer household didn’t keep that kind of money — more than Pete’s pension check — on the premises, so the next day Pete went to the bank for the funds. Joey was also ferried to the DMV to secure a photo ID. They seemed, for a time, like the happy little family that they had never been.

When informed that Jeff wouldn’t be joining them, Joey was annoyed. Why wouldn’t his little brother come to pay homage to him? he thought darkly. Idly, he opened the bottom drawer of the dresser they’d shared for years and extracted the more than 20 collectible knives that Jeff still kept there. Sneaking them out of the house, Joey rapidly sold the knives, which in 1984 dollars were worth more than $75 apiece, for pennies on the dollar, or for joints or pills, or what have you. He had taken his retribution.

& & &

1959

Five-year-old Jeff lay upon the stiff-cushioned, blue-upholstered sofa which served as his bed, trying in vain to find a comfortable position. His brother Joey, older by seven years, lay sprawled upon the small but much more commodious roll-away bed, listening intently to what transpired on the other side of their bedroom wall, where reposed the children’s parents. The tiny bedroom was utterly dark, but Jeff could see the whites of his brother’s eyes, illuminated by the streetlamp just outside the room’s one window. His face had a feral expression.

“Hey,” hissed Joey, leaning across to Jeff’s bed, “listen!” Jeff strained to hear, but could discern nothing. “He’s fucking her,” Joey said sibilantly. Jeff blinked. That was a word with which he was unfamiliar, except as part of an epithet frequently used by his brother; and frankly, he didn’t know what it meant. But he knew that, if Joey were using the word in any context, then it had to mean something terrible. Before Jeff could query his twelve-year-old sibling, Joey laughed darkly, menacingly. Jeff felt a chill.

“What’s it mean?” asked Jeff, genuinely confused.

“Last time I heard it,” remarked Joey cryptically, “you were born,” and his grin was the rictus of a living skeleton.

One Year Later

“Whattaya got?” squawked Jeff, observing his brother with an arcane object in his hands. The boys were outside in the vacant field adjacent to their home.

“Tape measure,” said Joey succinctly. “Borrowed it from old man Wankel,” he explained. Jeff knew this meant that his brother had probably stolen the device from their neighbor Mr. Wankel’s garage.

“What’s it for?” asked Jeff next.

“Shut up,” snapped Joey. “Here, take this,” he said, handing Jeff the end of the tape. Seizing it in his six-year-old hands, Jeff waited expectantly. Whatever it was, he knew it would be good. His brother was a genius. Backing away, Joey said, “start turning around,” and he twirled his finger. Without hesitation the younger child began revolving clockwise, absorbing the tape as he spun. When at length the tape was expended, Jeff was wrapped head-to-toe in 150 feet of tough, dense fabric. Joey approached his ensnared brother, contemplating his next move.

“I’m a mummy!” exhorted Jeff. “What happens now?” he asked. Wasn’t this great? he thought giddily.

“This,” replied Joey tersely, assuming a position behind his brother and pushing his shoulder. Jeff plummeted in seeming slow-motion, like a felled sycamore, and landed hard on his cherubic nose, which instantly broke and bloodied. “Later, Shithead,” murmured Joey dispassionately, spotting some friends in the distance and moving off to join them.

& & &

Throughout the late 1950s there generally existed a state of war at the small house on Central Avenue. One day, Jeff noted an awful, acrid smell in the air inside the little house. Swatting his way through the fumes of burning rubber, he arrived at the kitchen, where he found his coveted Zorro sword–just like they used on TV, he had learned–smoldering in mom’s cast iron skillet. He grasped the sword’s handle and nearly pulled the pan from the stove, so melded were they.

His face fell.

Jeff, under the influence of his brother, was beginning to think for himself a little. It was a matter of survival that he fight back. He sought revenge by unscrewing the cap on the bottle of Joey’s One-a-Day vitamins and holding the bottle under the water from the kitchen tap. In no time, his older brother’s daily vitamins were swimming in water.

“Mom,” lamented the 13-year-old, “my vitamins are all wet.” He looked as if he were set to cry, which immediately softened Jeff’s heart. He felt instant remorse. And he was surprised when his parents eschewed punishment for Jeff’s misdeed. Convinced that their youngest son must have been righteously motivated to act so out of character against their eldest, they patiently set out the waterlogged vitamins onto strips of wax paper. Jeff never heard word one with regard to reprisals. Unknown to either child, their mom gave Jeff points for creativity.

One day, several weeks before Jeff’s seventh birthday, he was busily combing the house for his present. He searched drawers, closets, wardrobes, the basement, the attic, you name it. At last he peeked under the mattress and found something; but what was it? He thought he recognized the metal device, but he wasn’t sure. So he did what he always did when he had a question: he asked Mom.

“Look what I found under my mattress,” he said, holding up the piece of metal like a trophy. “What is it?” he asked.

“That’s part of Joey’s gun,” she revealed, blushing a little. Her eldest had taken up hunting upon receiving a gun the previous Christmas.

“What’s it doing under my mattress?” Jeff wanted to know.

“I was afraid,” she told her son quietly, “that Joey might shoot your dad.”

Jeff’s blood ran cold. He hadn’t considered that, but it made perfect sense. His brother and his father often clashed, and inevitably Dad got the better of it. He was tremendously strong. Joey had never actually tried to punch back, however, and his father only slapped him with an open hand. No real damage — physically — was ever done. But Joey was prideful, as was his father.

“Put it back, honey,” his mother said softly. He obediently replaced the device, rearranging the bed clothes so as not to raise his brother’s suspicions. Jeff kept within his heart a hollow feeling of despair.

& & &

1962

Seated at the kitchen table in their newer, bigger home, Jeff munched enthusiastically on what was for his mother, a quintessential dish: SOS, identified variously as Same Old Slop, or more colorfully, as Same Old Shit. Joey picked through the culinary entity, composed of ground beef and milk gravy, rather indifferently. He ate little. Same ol’, same ol’, his body language seemed to say. Jeff, on the other hand, ate with relish.

“Joey,” said Mom, with concern, “you didn’t eat anything.”

Without even looking up, he muttered crossly, “We didn’t have anything.” Jeff glanced at his own plate, wondered if he should likewise feel dissatisfied; after all, his brother was the coolest person he knew.

Mom, of course, took offense. “You’re lucky you get that,” she snapped angrily. “You’re ungrateful, is what you are,” she declared, her voice rising.

“Richard,” he said spitefully, referencing his best — and wealthiest — friend for the moment, “is having steak and shrimp tonight.” Everyone had heard, many times, that Richard lived down at the marina, on his uncle’s 90-foot yacht. Mom could think of nothing to say. Joey effected a mean little sneer, then scraped his chair back loudly on the hardwood floor and left without another word.

After he’d gone, Mom asked Jeff, “Honey, do you want any more SOS?”

Although he was quite full, Jeff said, “Thanks Mom; it’s good!” The shadow on her face lightened at once. Jeff smiled.

& & &

In the autumn of 1964, the boys’ paternal grandmother died. To Jeff this was an unexpected reason to miss school and receive bounteous foodstuffs from friends and neighbors. But to Joey, it was an unwelcome interruption in the grand scheme of things. As the first of Bessie’s grandchildren, he had occupied a special place in her heart, whereas Jeff had lingered on as a mere afterthought. He had hardly known her. The incipient drama, for different reasons, was a little much for either child to bear. Time spent at Grandma’s home was markedly weird without Grandma, more so for Jeff than for his older brother. Joey was content to detonate crackerballs, tiny explosive missiles, sold in 10-packs for a dime, on the sidewalk. Jeff avoided the gloom-shrouded house, with its huge, creepy lamps, disconcerting shadows, odd bric-a-brac and strange fabrics. The ghost of his grandmother seemed to occupy the domicile. Joey, on the other hand, was less of a loner than was his sibling; he required friends his own age, as well as specimens of the fairer sex, with which to ameliorate his trauma. So, Joey journeyed far and wide and stayed out late. On several occasions, he made the unwanted acquaintance of the local police. The tension was building.

One day, trapped in a car with Uncle Art, Dad’s sister’s husband, Joey and Jeff came to blows. “Little sonofabitch,” snarled Joey, backhanding Jeff viciously across the face. The ten-year-old felt his lip bleed, but of course, he couldn’t keep still, and protested, which prompted Joey to slap him again, loudly.

“Little sonofabitch,” gritted Joey again, enraged that his brother should object to Joey doing whatever he would. If Jeff had been anticipating Uncle Art to take a hand, he was sorely disappointed, for Art lifted not a finger. His uncle and his cousins viewed the scene dispassionately, their heads moving from side to side, as if at a tennis match. Joey beat Jeff wantonly. It was neither the first nor the last time.

& & &

Joey was always in trouble, if not with the neighbors or teachers or young girls’ fathers, then with the police. When he was ten years old, Joey pounded pennies into dimes with a hammer and fed them into vending machines at the laundromat. He overloaded the washers with soap until they overflowed, inundating the building. Consequently, and to the utter humiliation of Mom and Dad, Joey appeared in juvenile court and was summarily convicted of various offenses. The youth was ordered to pay a fine of ten dollars and to attend the church of his choice for six months. The fine, of course, came out of Dad’s wallet He earned two dollars per hour at the local glass factory and this came as a stunning blow to the Schafers’ personal finances, which already were stretched tight as a string. Because he had to attend church, Joey insisted on having money to put in the collection plate.

“I can’t be the only one not to put something in the collection plate,” whined Joey, holding out his hand.

Pete gave him quarters and Joey used them to buy cigarettes, which cost twenty-five cents, back in 1957. At length, probation ended and Joey got into trouble again, first by cutting school and then by shoplifting a drug store and then by breaking and entering, several times.

& & &

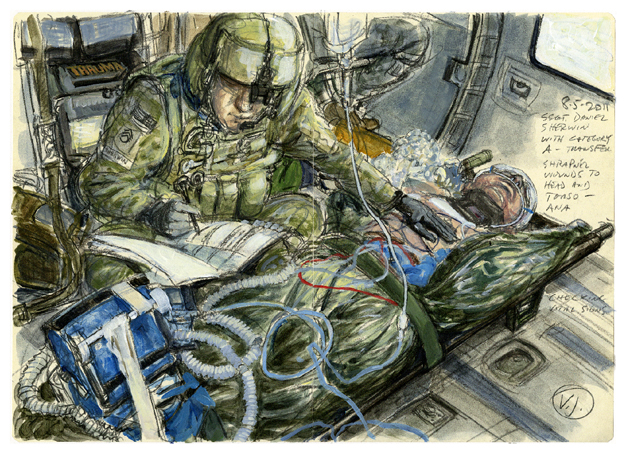

Viet Nam

Finally, when he turned 18, Joey stopped getting off so easily. “You’re a recidivist,” scolded the silver-haired judge sourly, addressing Joey in court one day. “You’ve got no direction, no impulse control, no nothing. You have a choice: six months in the penitentiary or join the Army. They’re always looking for men.” The judge smirked. There was really no choice; Joey joined the U.S. Army that fall.

In the weeks leading up to Joey’s induction, Jeff, now eleven, felt closer to his brother than ever before. Joey treated him, for the first time, like a brother–the way that other brothers seemed to treat their siblings–and not as merely a pain in the ass. Joey solemnly bestowed on his younger brother some of his mementos, keepsakes and other oddments. Jeff awkwardly accepted them. One of the items was a small soapstone hashish pipe, in the use of which Joey instructed his brother.

”I’ll want this back when I come home,” said Joey, reluctantly handing it over. “And here,” he said, passing Jeff an unsealed package of extra-large condoms. The younger brother blinked down at the prophylactics.

“I don’t even date yet,” he murmured.

“You will,” asserted Joey positively, “if you’re any brother of mine.”

At the bus station, Mom and Joey embraced one another and Dad gravely shook his son’s hand, the first time that Jeff could remember the men touching, but not in violence. Then Joey was gone.

Viet Nam in 1965 wasn’t the hellish inferno it became two years later. Hippies hadn’t coalesced into battalions of protesters yet; LSD-use was in its infancy; and the chant, “Hey, hey, LBJ; how many kids did you kill today?” was as yet unspoken. Things would change radically over the next several years. When it was learned that Joey was being deployed to Viet Nam, Mom wept.

Jeff cherished every infrequent letter which Joey sent him. Mostly, the letters, thin blue envelopes addressed in Joey’s indecipherable scrawl, went to Mom, who of course shared them. Joey also sent things home, what with military franking privileges: a leather wallet for Dad, a Persian rug for Mom, a shirt for Jeff. Curiously, he also sent home many cartons of cigarettes. Mom and Dad were too hopelessly straight to realize that the smokes were in fact professionally rolled marijuana cigarettes. The cartons were merely stored in drawers in the bureau in the brothers’ bedroom, awaiting Joey’s hoped for return.

& & &

In 1967, Joey returned from Viet Nam, with a less than honorable discharge, yet another badge of shame: “Mrs. Schafer,” wrote his sergeant, “Joey was never a good solder…” And so it went. And he must have been a poor soldier indeed to be set free by a military in such dire need of more recruits. Hundreds of G.I.s were perishing every week. Upon arriving home, Joey reconnoitered with friends, ignored his family–but for swiping the household’s collection of Kennedy half dollars–and then fled for the West Coast, in search of his next adventure. There, he morphed into an honest-to-God hippy. Just like on TV.

Jeff, meanwhile, now 13, fought the wars against acne, awkwardness, and loneliness. The first time that Jeff made love, he was 17. It was with a young woman whom he loved passionately and who returned his feelings. The first time that he had sex, however, he was just 13, and love played no role in the procedure. His first sex partner was a lewd, gruff 17-year-old with a dark beehive hairdo and a brisk, no-nonsense manner.

“C’mon,” she said, leading him to the backseat of a Plymouth parked under a shade tree. Sliding along the nylon bench seat after her, he was wide-eyed with apprehension. His brother had arranged all this, because he was embarrassed that his brother, who was now in junior high, hadn’t yet had any “tail.” Not the least part of it was that Joey’s friends had taken to referring to Jeff as “your queer brother.” Joey had informed him that he would lose his cherry to someone named Sharon.

“Get undressed,” she ordered him, removing only her tight skirt and then her panties. Her blouse and her shoes remained on. The beehive danced against the rear window. She had massive breasts, thought Jeff. Quickly he disrobed, then waited expectantly. Next to him on the blue-upholstered seat, she spread her legs, pointed to her bare privates and said, “Do your business.” Jeff had read Playboy Magazine and so he was surprised to discover that women had hair on their genitals. Jeff took a breath. hovered uncertainly over her prone form for a few moments, before she impatiently grasped his virgin manhood and forcibly inserted it into her vagina.

Yikes! thought Jeff wildly, I’m actually doing it. No more than five minutes later, the experience had concluded and Sharon was impatient to quit the love nest. She donned her panties and skirt again, shoved past him on the seat and left without another word. What a disappointment, thought Jeff, pulling up his jeans. It was so impersonal, more impersonal even than masturbating, which his mother had said would turn him blind. He shook his head, was reminded of a joke his friends told: “I’ll only do it till I need glasses.” Sex, despite all he’d heard about it, was not what it was cracked up to be. In fact, it was four more years before he took another lover. At least I saved my eyesight, he thought bleakly.

& & &

In Prison

Once Joey got out of the Army, his criminal ways did not change. Ensconced in his hometown once again, he consorted with the same typically unsavory sorts. Arrested in 1972 for “possession of burglary tools,” — a screwdriver and a crowbar — he was assigned the requisite public defender, who proved his abject inadequacy and steered Joey into state prison for 15 months. Everyone knew that a “real” lawyer would haven gotten Joey off with only probation, but lawyers cost more than the Schafer house was worth and the new felon’s parents reluctantly turned Joey down and abandoned him to the system.

Jeff went to see his brother in the county jail. Joey was surrounded by an entourage of long-haired men and skanky women. Joey himself, whom Jeff had not seen for five years, sported a Rapunzel-like mass of hair that spilled down below his shoulders. Jeff hadn’t seen hair that long but on TV. He stood stoically, waiting for Joey to acknowledge him. He never did, so Jeff left. This was familiar territory for him.

After Joey was sentenced to Menard Correctional Facility, Joey’s girlfriend, Vada, contacted Jeff, urging him to visit his brother in prison, which was a hundred miles distant. “Joey really wants to see you,” she said earnestly.

“He does?” he asked uncertainly.

“Sure he does. And could I ride over with you?” Vada had no car. The trip to Menard was uneventful. Vada was a slick, shiny, slender girl of about his brother’s age, who had been with him, she said, for about two years. Jeff had never before known that she even existed. As they approached the facility, she told Jeff to slow down, to drive down the gravel road outside the eight-foot chain link perimeter fence. The facility was enormous. Jeff glanced uneasily at the razor wire strung along the top of the barrier.

“Stop here,” Vada instructed. Climbing out of the car, she tossed a collapsed milk carton over the fence, then said, “Okay, let’s go.”

“What was that?” inquired Jeff.

“Pot,” she answered succinctly. “The guards will retrieve the stash and then share it with Joey, fifty-fifty,” she explained. Jeff hadn’t considered this, but it was another of those things that made perfect sense. In his letters home, Joey had said that drugs were rife among the inmates. The universal currency, he said, was cigarettes, or “squares,” as they were known. They were transferrable into anything: joints, downers, uppers, alcohol, sex, all the necessities.

When they got into the prison proper, after having submitted to repeated patdowns — Jeff noted that the shapely Vada was felt up at length, or so it seemed — they were allowed into the visitors’ room, a large chamber divided into row upon row of double desks that were separated by low partitions. They reminded Jeff of miniature, maple-finished ping pong tables. When they approached Joey, he immediately jumped to his feet and arduously kissed his lover.

“Hey, baby,” said Joey passionately.

To Jeff, he only nodded perfunctorily. When told that Vada had ridden over with his brother, Joey turned gray and nodded sullenly. Vada hurriedly assured him there was “nothing going on.” Jeff blushed, shook his head, humiliated that his own brother would even suspect such a thing. The other two talked rapidly and in some kind of code, or so it appeared. At one point during the 30-minute visit, Joey asked Vada to get him some “brake fluid” in the next drop. But, this went completely over Jeff’s head. Finally it was time to depart. Again, Joey earnestly kissed his girlfriend, but this time he didn’t even look at his brother. Jeff stared at his departing, chambray-clad back. Subsequent visits did not happen, as Vada secured her own transport and curtly informed Jeff that since only one visit was permitted per month, his presence was not required — or wanted.

Although the visits were stopped, Joey’s letters to Jeff continued, if only for comic relief. In one missive, Joey stated that he had been busted by “the man” for skullduggery. Gaining access to the prison kitchen, Joey and a cohort had purloined a five-gallon restaurant-sized drum of peanut butter and a store of saltines, and proceeded to sell them to other inmates for the unversal currency of cigarettes. Upon being busted, Joey asked rhetorically, ‘What are they gonna do, put me in jail?” Jeff had chuckled at his brother’s mirth. He didn’t know it then, but Jeff would never see or hear from his brother again.

Coda

2019

Jeff stepped through the door of the funeral home, felt the warm smile of the nice lady who was the funeral director. She was also a distant relative, who had often befriended Mom. She escorted him into the “Slumber Room.” There Jeff found three elderly women his mother had known. They each told him how sorry they were, how they would miss his mother, and they hugged him. Jeff felt his eyes swim with tears, but he didn’t allow them to fall.

He went in to view his mother, looking beautiful in the dress the mortician had purchased for the occasion. Jeff knew that Mom, from a life spent just north of the poverty line, had no clothes befitting such an occasion; he shook his head sadly. He gazed down at her prone form: though the staff had asked if he wanted her opal ring — her favorite, and a gift from him — removed before interment, he’d insisted that she keep it — for eternity. At the conclusion of the well-attended service, he walked out, the last to leave, but for a youthful-looking blond man of about 70, who spoke Jeff’s name.

“You probably don’t remember me, do you, Jeff?” he asked quietly. Although he hadn’t seen Mike in nearly fifty years, he recognized him instantly. He said so, told him that he looked good. “Seen Joey lately?” Mike asked.

Jeff shook his head no. “Haven’t seen him in over forty years,” he replied.

“Haven’t heard from him either?” Mike inquired further. Jeff shook his head again.

“The last I saw of him,” said Mike, “was back in 1984.”

“That’s when he was at Mom and Dad’s last,” remarked Jeff, remembering. “When did you last hear from him?”

“About a year later. Well,” said Mike, “I actually heard from Vada. She was still with him then.” He paused.

“So what did she say?” asked Jeff.

“She said,” Mike replied, “that Joey was involved in some kind of shady scheme in Arizona.” He hesitated again and Jeff began to feel antsy, wishing he’d continue. “Vada said,” Mike went on, in a hollow-sounding voice, “that three men went out into the desert, but only two returned. And Joey wasn’t one of the two.” Jeff nodded numbly and then Mike shook his hand and withdrew,

So, there it was, thought Jeff, receiving answers to his unspoken questions at last. Joey hadn’t been so cruel and crass as to stay away from his parents for thirty-five years; so unfeeling as to avoid the funerals of both Mom and Dad; so indifferent as to abandon Jeff for most of his brother’s adult life–maybe. As he rode to the cemetery, he thought: today I’m saying goodbye to the rest of my family. As he grieved anew, the long-awaited tears finally came, swimming in his eyes and rolling slowly down his cheeks.

* * * * THE END * * * *

Copyright Bill Tope 2024