Trotsky’s Train by R. K. Olson

EDITOR’S NOTE: You can read three other Adventure stories by R.K. Olson on FreedomFiction.com , This story features the character Jackie Boyd and his continued adventures through war and valor. This is the third Boyd fiction appearing on FreedomFiction.com — the previous two in reverse chronological order of publication are:

The Tsarina’s Jewels by R. K. Olson (August-2024)

https://www.freedomfiction.com/2024/08/tsarinas-jewels-by-r-k-olson/

The Vladivostok Express by R. K. Olson (April-2024)

https://www.freedomfiction.com/2024/04/the-vladivostok-express-olson/

Other Adventure story sans Jackie Boyd from R. K. Olson involves ancient lore of kingdoms and kins

Two Kings For Toltan by R. K. Olson (January-2024)

https://www.freedomfiction.com/2024/01/two-kings-for-toltan-by-r-k-olson/

* * *

Trotsky’s Train by R. K. Olson

A single gunshot cracked the icy air and echoed across the gloom of a frozen Russian November morning. A body crumbled to the snow. Lying on the ground, the body looked like a pile of rumpled clothes.

Red Army soldiers with Mosin-Nagant rifles slung over a shoulder, lined up in ranks and stared ahead, rigid witnesses to the penalty for cowardice in the Russian Red Army of 1920 during the Russian Civil War. Ice crystals dropped from the leaden sky, peppering the men’s faces with little pinpricks. The crystals slipped down collars and melted inside jackets against bare backs.

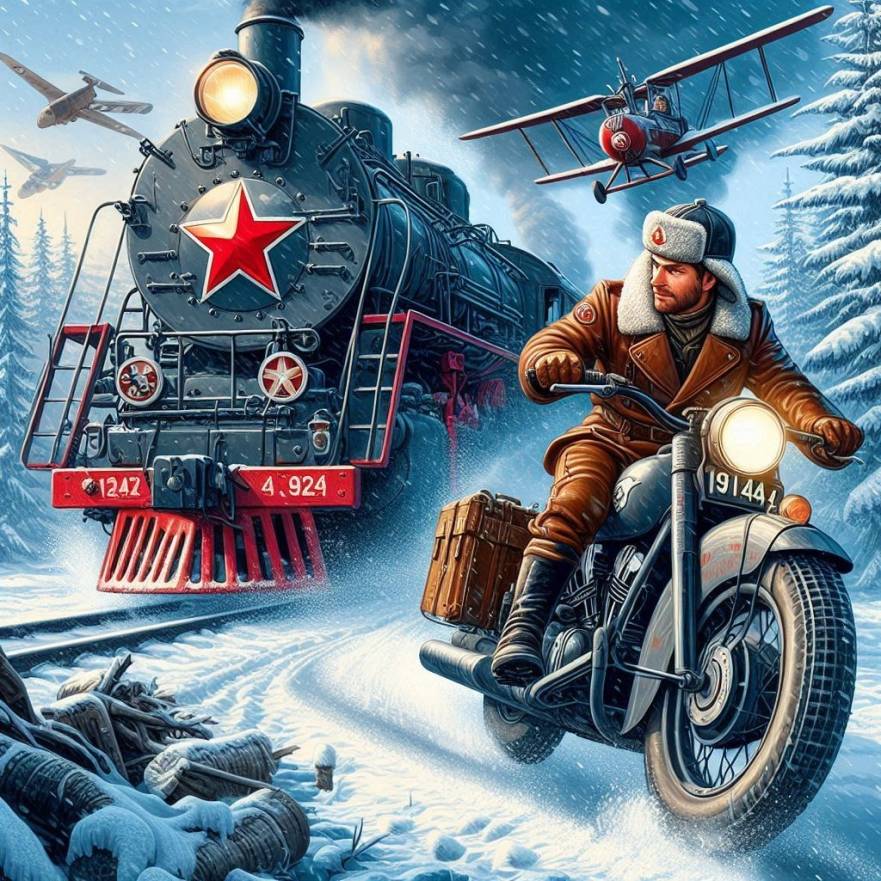

The soldier holstered his heavy Nagant 1895 revolver. He wore the red leather uniform and peaked budenovka hat of the elite guard unit of the armored train called ‘Predrevoyensoviet’ – the train of the Chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council – or, simply, “Trotsky’s Train”.

For two years, it served as the Red Army’s mobile supreme command post and Leon Trotsky’s permanent home. The steel-plated armored train huffed and puffed on the tracks in front of the ranks of soldiers spewing ash from the engine into the gray, somber sky. The armored train exuded a nervous energy and an impatience to start.

The soldier with the pistol looked up at the gangway between an armored railroad car encased in cold, hard, four-inch thick steel painted a mottled greenish-gray and a flatbed rail car carrying a turreted armored car. All along its length, the train bristled with gun ports, machine guns, and heavy artillery.

He crisply raised his right hand to the temple and held it there until the man standing on the gangway acknowledged it with a nod of his head. The man wore round glasses and a well-trimmed goatee. A thick thatch of dark hair sprawled over his head.

A wheezy train whistle etched the crisp winter air. Comrade Trotsky, on the gangway, ducked back inside the armored rail car.

The train shuddered and shook before it inched forward in a slow steady churning of steel wheels on steel tracks, producing an unholy, God-less shriek of the damned. The soldier in red leather grabbed the train’s gangway railing and swung up into the moving train.

Two hundred soldiers standing in rows at rigid attention remained unmoving as the hulking Trotsky’s Train began moving at a walking pace. The kitchen car was followed by cars for a bathhouse, library, telegraph, and radio office, an electrical generation wagon, armored cars, turreted gun wagons, a special flatbed with a small collapsible biplane and a printing press for the train’s official newspaper, “En Route”.

Trotsky’s Train faded from view in the early morning, swallowed by low clouds that curled around the soldier’s ankles.

“Dismissed,” yelled an officer with what looked like steam shooting from his mouth. Sergeants repeated the order. The soldiers relaxed and crunched heavy boots through the snow, forming small groups and sharing cigarettes.

A thin, papery train whistle reached the soldiers’ ears from down the track

& & &

Jackie Boyd turned his face away from the warmth of the winter sun and watched her walking toward him up the street. She had the effortless, graceful movements of a former ballerina. Like Boyd, she was around thirty years of age. Her fur coat was open at the neck and brushed her ankles. She raised her hand to acknowledge Boyd. He didn’t reply. He stood from the cafe table and brushed off his leather flight jacket and khaki trousers with his hands. He crossed his arms over his chest.

The woman’s pale skin contrasted with her ink black hair and the deep red of her lipstick. Her exposed throat was long and taut. Boyd pulled out a chair from the cafe table and the woman seated herself in it. She smiled and her pale blue eyes crinkled at the corners. Her perfectly proportioned face had cheekbones sharp enough to cut glass.

“Thank you, Mr. Boyd,” she said in heavily accented English. “Would you be kind enough to order me a tea, please?”

“Okay, Sofia.”

Boyd motioned to the fat man behind the counter in the empty cafe and sat back down in his wood chair. In a moment, the cafe owner placed a steaming cup of tea in a porcelain teacup and saucer on the scarred tabletop. Sofia flashed a brilliant smile at the server.

“Spasibo” (Thank you) she said.

The server’s face flushed and he bowed awkwardly before returning to his station behind the counter..

She blew on her hot tea, watching a person carrying a stuffed backpack with a frying pan and a pair of shoes dangling off it hurry to Sevastopol Harbor, and if the price is right, buy passage out of Russia and across the Black Sea. Away from the horrors of war and the Red Army. Away from Lenin and Trotsky. Away from Russia.

She flitted her eyes back on to Boyd. She arched an eyebrow and scanned his black close cropped hair, brown-skin, leather jacket, and khaki pants with a positive appraisal. Her blue eyes meet Boyd’s dark eyes. She fluttered her long black eyelashes and laughed in her throat.

“Nice coat,” said Boyd.

“A gift from a friend for cold Russian nights.” She held the teacup with both of her slim hands. Sofia sipped her tea and gave a thin smile. “What gift do you have for me, Jackie?”

“I was at the Isthmus of Perekop yesterday on a reconnaissance flight. It’s a matter of time until the Reds breach its defenses,” said Boyd.

“Tell me something all of Russia doesn’t already know. Or I’ll keep my French friend’s money in my pocket.”

Boyd ignored the comment and pulled an envelope out of the inside pocket of his leather jacket. He placed it on the table. He kept his brown, rough hand flat on the envelope.

“Red and White Army troop strengths and deployments at Perekop,” said Boyd.

“Da, how did you get this information?”

“From multiple sources and confirmed with my own eyes yesterday,” said Boyd. “This should be worth French gold.”

She reached out and softly patted his muscular hand covering the envelope. She sighed and pulled out an envelope and put it on the table next to the first envelope. Boyd moved his hand from one envelope to the other and tapped Sofia’s envelope with his index finger.

He frowned.

“I get paid in gold. Not paper.” He rifled through the envelope stuffed with French currency. “I wipe my ass with this play money.”

Sofia finished her tea. Her nails were perfectly groomed and unpolished. “My contacts in the French government are using gold to buy passage out of Sevastopol. These francs have value in every civilized spot in the world.”

“Jesus, I guess I’m not civilized. Our agreement was for payment in gold,” said Boyd, standing up. He moved like a cat. Boyd was of medium height, compact, with broad shoulders and lean hips. A broom handled Mauser poked out of a shoulder holster under his lined leather jacket.

“Don’t you have any feelings for France, the country you flew for in the Great War?”

“I fought dogfights over the trenches for France because they gave me a chance to be a pilot. America didn’t want a negro pilot. Now, I’m flying for profit. That means gold.” He put both hands on the table and leaned across it. His smooth, brown, angular face loomed a foot from the woman’s face. “I’m the best damn pilot in Russia. I want to be paid in gold.”

Her eyes flexed wide for a moment. “Money is money. It’s the best deal you are going to get in Sevastopol.”

“You’re spying for the French out of patriotism, I guess?” He said in a mocking tone.

Sofia’s eyes blazed cool blue fire crystals. She snatched up Boyd’s envelope and nodded to Boyd. She turned, whirling her fur coat around her lithe body, and marched down the street among the handcarts and people flocking to the harbor.

He dropped two kopeks on the table and stuffed the envelope with the French francs in the pocket of his leather jacket. He shook his head and walked with an easy, loose step in the opposite direction down the street.

He turned right and ran into three drunk soldiers wearing the green uniforms and heavy green wool great coats of the White Army.

They must have been drinking all night.

Boyd brushed his way through the soldiers. One reached out and grabbed his shoulder. Boyd slapped his hand off.

The largest soldier laughed, “Must be a minstrel show around here. We don’t see many ink-stained men like you!” The other soldiers were holding each other up. They snorted at their friend’s comments. “Hey, boy, how about a song, eh?”

America … Russia … everywhere, it’s always the same.

He recalled an incident twenty years ago when he was a small boy and witnessed his father backing down to four white men. They told his father to get out of the dry goods store because it didn’t serve niggers. The men’s laughter followed his father and Jackie out the door.

His father explained to the young Jackie that four against one were long odds and why get killed over it? He’d come back later when the men had left.

Anger and shame collided inside the young Jackie. Impotent fury followed. Since then, this fury bubbled inside Boyd until it spilled over into silent, deadly action.

Like a snake strike, Boyd’s hawser-like muscles darted a left jab and caught the larger soldier in the mouth, splitting his lips. Then he snapped a right cross, shattering the soldier’s jaw. The soldier’s knees buckled and he collapsed on the dusty street.

Boyd pivoted with his hips, buried his left fist in into a soldier’s wind before kicking the third drunk soldier in the groin. People stepped over the prostate forms of the three soldiers and continued on their way.

Well Pa, sometimes – even with the odds against you – you should still give it a shot.

He checked the drunk soldiers for weapons and valuables. He didn’t find any, so he left them to moan in the street.

Boyd turned down an alley on his left. He smelled the pigeon coop and heard the soft cooing before he could see it.

As Boyd reached the coop, a pigeon landed on the roof and clattered through the one-way pigeon door. An old man with a black eyepatch known as the “Pigeon Master” was sitting on a box with his back against the unpainted coop.

Someone had slapped together the eight-foot-high rectangular coop from scrap wood. The door for the pigeons to enter and exit was on the roof in the center of the fifty-perch coop. Three sealed grain bins lined a fence behind the coop.

The old man got up, stretching his back. He was wearing the traditional tall, round fur Cossack cavalry hat called a papakha. His gray wool coat reached beyond the tops of his down-at-the-heels black riding boots. The coat’s neck and cuffs displayed silver trim, and the jacket’s chest featured sewn-on cartridge pockets.

The Pigeon Master banged his pipe on the side of the coop to empty the bowl. He gave a wave of acknowledgement to Boyd and limped into the coop to retrieve the message delivered by the pigeon. Silver metal capsules attached to a pigeon’s leg carried military correspondence on small slips of paper between Sevastopol and the front.

The Pigeon Master slammed the coop door shut and limped over to a dozing man in a green infantry uniform man sitting on the ground with eyes shut, feet crossed at the ankle, and his back against the fence. The old man carried a large red and white spotted pigeon in one hand and two silver capsules containing messages from the front in the other. He dropped the silver capsules in the sitting man’s lap, waking him up. The man grunted and hopped to his feet, adjusted his kepi and ran down the street with the messages from the front gripped in his right hand.

“How are they flying, Dmitry?” asked Boyd in rough Russian laced with English.

“Better than you,” laughed the old man, his one good eye lost in his lined and seamed face. “Meet Big Red. My favorite bird. He’s been with me for two years and never fails. More reliable than telegraph or telephone.” He stroked the pigeon’s head with a grimy finger.

“What’s the news from your pigeons?” said Boyd. He grabbed a floor scraper and entered the coop. He pushed the pigeon droppings across the floor and out the back door as Dmitry watched with a smile creasing his broad, gray-whiskered face.

“You know I’m not supposed to read the messages,” said Dmitry. He winked and placed Big Red back into the coop.

“This civil war is over. Lenin won,” said the old man, taking the scrapper from Jackie Boyd. “I miss the Tsar. Things were more orderly. Everyone knew their place. People weren’t as hungry as they are now. I’ve had to stop more than one person from trying to steal a pigeon for their dinner or eat my grain I use for the birds..”

“I hear the Reds are planning a massive offensive,” coaxed Boyd.

“They have us bottled up in the Crimea. Jackie, the Reds have the men to smash through our fortifications at the Isthmus of Perekop. One message reported that Trotsky’s armored train arrived at the front yesterday,” he added, “Look! Your British friend.”

He pointed at a wiry, nattily attired older man with a big toothy grin sauntering down the street swinging an umbrella.

“Chyorny Pilot! (Black Pilot),” said the slim British man, Davis Taylor, in flawless Russian. A dark blue cravat poked out of the top of his white shirt, wrapped in a Harris tweed suit jacket. “On time as always! Your dedication to duty is astounding!” Taylor’s grin didn’t reach his eyes.

“It’s my dedication to money that is astounding, Taylor,” replied Boyd. He unconsciously touched his waist where he concealed his money belt.

“Bully for you, Boyd!” Then, in a whisper, “What do you have for me?”

“Troop strengths and dispositions for both sides at the Isthmus of Perekop,” said Boyd, glancing up and down the street. “Flew over it yesterday.”

Dmitry sat down with a grunt near the coop and fiddled with his pipe. The rich moist aroma of the Dmitry’s pipe tobacco lingered in the air, making Boyd’s nose twitch.

“Bully!” said Taylor. He reached inside his suit jacket and pulled out a small leather bag. “Gold sovereigns, as agreed.” He gave the bag a shake and Boyd heard the “ching” of metal coins.

Boyd dug in the pocket of his khaki pants and pulled out a folded piece of paper, and handed it to Taylor. While Taylor scrutinized the paper with quick, hungry eyes, Boyd counted the sovereigns.

“Outstanding, Boyd. It’s all there. I counted it myself,” said Taylor. “You are making a great deal of money from this war. Where do you keep it all?”

“Good doing business with you,” said Boyd.

“Cheers! Dasvidaniya (Goodbye)! You hear anything else, you know how to find me!” Taylor strolled back the way he had come, swinging his umbrella, avoiding the growing traffic in the street streaming to the harbor. Crowds filled the streets as much as during festivals.

A motorcycle horn sliced through his thoughts and Petrov, a squadron mate, braked the United States-made Indian Scout motorcycle with a squeal next to Boyd.

The motorcycle was one of the many delivered to the White Russians by America’s Lend-Lease Program. People prized the Indian Scout for its durability and ease of maintenance. Its 600cc V-twin engine delivered ample power, and featured a three-speed transmission suitable for various terrains. It was painted black with wrap around handlebars, straight pipes, and wire wheels.

“Jackie, jump on. Volkov wants all flyers to report to the airfield now. He wants us in the air this morning,” said Petrov. Excitement flushed his smooth, round face. He revved the Indian Scout motorcycle engine and spewed hot exhaust out of the tailpipes.

“Why?” Boyd lifted a leg over the motorcycle and sat behind Petrov on the motorcycle’s leather seat.

“No idea. Remember, you promised to teach me how to do a hammerhead turn.” Petrov grinned at Boyd. Petrov was young enough that his face still had baby fat. He gunned the motor and the back tire spun until it caught on the cobblestone and rocketed the motorcycle forward, swerving around people, bicycles and a horse-drawn carriage heading to the harbor.

& & &

Volkov’s meeting was short. Jackie Boyd was in the air within an hour executing what Volkov had named “Operation White Eagle.”

Boyd snatched a glance below from the cockpit of his French-made Nieuport biplane flying north from Sevastopol, thousands of feet over the Crimea. The terrain was a rough checkerboard of snow-covered fields and green pine forests. Stands of oak, beech, birch, and ash interrupted this pattern. The trees stripped bare of their leaves, preparing for another harsh Russian winter.

He loved the moment the biplane escaped gravity, and he was free of the earth. It sparked a warmth in his belly. His cares and worries melted away. The sun was bright and the air clean and cool this morning. It was a good day to fly.

Fly Jackie Boyd fly.

His sheepskin-lined leather jacket and wool socks fought off the cold. He had wrapped a scarf around the lower part of his face for added warmth. Boyd held the control stick with both hands. The tips of his fingers inside his leather gauntlets were stiff in the Russian November morning air. He sucked in a lungful of fresh, tangy air, expanding his chest and feeling the icy air reach every corner of his lungs.

His squadron’s five Nieuports flew in a ragged line, sighting off Boyd’s biplane, serving as an escort for the slower Voisin bomber aircraft. Petrov always flew to Boyd’s left.

All Boyd wanted to do was fly. And get paid. Serving as a mercenary pilot for the White Army in the Russian Civil War got him both. He flew every day, when weather and repairs permitted. They paid him in gold, not paper currency, and he had accumulated a tidy sum hidden in Sevastopol.

He smiled underneath his scarf. He remembered all the twists and turns it took to become a pilot for France in the Great War. He flew for the first time five years ago. He’d never forget that day. He also wouldn’t forget the promise he made to himself when he hopped a freighter to France to enlist in the French army that someday he’d return and land a plane right on the main street of his hometown.

Petrov flew closer and waved to Boyd with a wide grin on his face.

Boyd cranked his head around and spied the four Voisin bombers the fighters were escorting to the target.

Wing Commander Volkov’s briefing on Operation White Eagle took less than ten minutes. The Red Army had the White Army bottled up in the Crimea Peninsula. A fortified, narrow strip of land controlled by the White Army attached Crimea to Russia. Called the Isthmus of Perekop, it was a straight line from there one hundred and twenty miles south to Sevastopol. This was shaping up to be the last stand of the White Army in the Crimea.

Petrov had translated the briefing details for Boyd. According to Volkow, Trotsky’s Train was near the Isthmus of Perekop. Command ordered the Voisin bombers to destroy the train tracks in front of and behind the armored train, pinning it down for a combined White Army armor, air, and infantry attack.

Boyd agreed that capturing or destroying Trotsky’s Train would be an enormous morale boost for the White Army. However, Trotsky’s Train’s four-inch thick plated steel shell and armaments made it impregnable. Attackers would face machine guns, heavy artillery, and a one hundred-man elite fighting force distinguished by their red leather uniforms. They were called the “Red Guard” and would fight to the death to protect Trotsky and his train.

A hard nut to crack.

Boyd waved to Petrov and made the signal to land the squadron on a large flat field near the village of Dzhankoi that was the staging area for the assault on Trotsky’s Train. It was about twenty miles south of Perekop. The plan was to transport the troops by truck to Perekop and attack Trotsky’s Train quickly. The tanks and armored cars had started forward a while ago to get into position for the assault.

Boyd watched trucks loaded with equipment and men hanging off them like monkeys grind forward. Then he used his limited Russian to check in with each fighter and bomber pilot in this makeshift squadron Volkov had thrown together to confirm refueling was complete and that they understood their assignment in Operation White Eagle.

“Ready to go?” said Petrov, jogging over to Boyd. “I never attacked a train before.”

“The bombers will do most of the work. We’re there to keep the enemy fighters away and lay down a strafing run or two. Come ‘on let’s get flying. With any luck, we’ll complete Operation White Eagle and be back here by lunch.”

& & &

Trotsky’s Train slithered through the frosty November night like an undulating serpent. Its electric lights reached out into the Stygian darkness of the Russian landscape, illuminating for an instant forests and farmlands before plunging again into the solid black curtain of night.

Steel plating on all sides of the armored cars, including the roof, protected it against small arms fire and shrapnel. The train was equipped with machine guns, artillery, and anti-aircraft weapons. It carried armored cars with rotating turrets and gun emplacements. The train’s engines pulled rail cars for troop transport and flatbeds carrying automobiles, biplanes, and other equipment. Specialized rail cars carried ammunition, spare parts, and supplies.

A cold, gray morning slipped into a clear day as the sun burned off the clouds. Trotsky’s Train came to a slow, screeching halt directly behind the Red Army entrenchments at the Isthmus of Perekop. One hundred and twenty miles to the south lay Sevastopol and the destruction of the remnants of the southern White Army.

The muffled knock on the door caused Comrade Trotsky to sigh. He put the paper he was reading on the desk in front of him.

“Enter,” said Trotsky.

A captain of the elite Red Guard marched into the room and pulled himself to attention in front of Trotsky. Trotsky took off his round glasses and cleaned them with a handkerchief.

“Well?” said Trotsky.

“Reconnaissance reports that the White Army is advancing on this position with armored vehicles and infantry. I suggest we remove this train from the area,” said the captain.

“Thank you for your concern but we aren’t moving away from a battle.” He smoothed his goatee with the thumb and forefinger of his right hand.

“With your permission, I will ready your car and airplane in case they are needed.”

“As you will, captain,” Trotsky ran a hand through his thick, dark hair and said, “Inform the Red Guard to deploy on the south side of the train. I want all train support personnel – cooks, cleaners, mechanics, printers, etc. – issued rifles and deployed as well. All available planes should be in the air. Tell the troop commanders to prepare to advance.”

“Advance?”

“Correct. Advance. We will fight fire with fire.”

An explosion rocked Trotsky’s rail car. The lights flickered. The captain absorbed the shock with bent knees, his eyes wide and round. He assumed the position of attention again. Trotsky didn’t look up from the sheet of paper in his hands.

“You are dismissed. I have an article for ‘En Route’ to edit. Thank you, captain.”

& & &

Boyd feathered the control stick, and the biplane responded like a skittish colt. The other fighters had formed a rough “V” pattern in the sky, with Boyd at the apex.

Below, the White Army looked like ants crawling over a sheet of white paper. He spied two British-made Mark V tanks and a machine gun armored “whippet” tank plowing through the snow. They ground forward at a walking pace. Armored cars with mounted machine guns covered the flanks. Infantry men vied with each other to get a spot behind the armored vehicles for cover as they plodded forward in the snow. The lucky infantry soldiers riding in trucks passed by the walking men and jeered.

Boyd looked up in time to see the first bomb dropped by a Voisin bomber explode against the roof of a rail car. The Voisins were pusher aircraft, meaning the propeller was in the back of the biplane. They were slow but nimble and could carry three hundred pounds of munitions on racks under the wings or fuselage. The observer, who sat behind the pilot, manually released the bombs using a lever.

Boyd reckoned the White Army could hold their position across the Isthmus of Perekop for a week or two. Then fight a delaying action down the peninsula until they reached Sevastopol and its vast deep-water harbor. The White Army could escape Sevastopol by the end of November because the harbor didn’t ice over in the winter.

He’d be out of there with his money long before the Red Army showed up.

He smiled, loosening his square jaw for an instant. The last year was lucrative. The job was like flying for France in the Great War — mostly reconnaissance and escort duties — except that he got paid a lot to ply his skill.

A black man getting paid to fly. Chyorny pilot. Black pilot. That’s what they call me.

He caught a flash out of the corner of his eye and, turning his head, spied three Red Army Nieuport fighters at ten o’clock flying due south. Both sides in the war used the same equipment and wore similar uniforms. It was hard to tell friend from foe. Boyd liked it because no one pilot had a technological advantage of a superior biplane. It was all about skill. And luck.

The three attacking planes separated into attack formation and Boyd did likewise, along with his fellow White Army pilots. The sun inched higher in the sky, an impartial witness to the dogfight.

I’m about to fake you out of your shoes.

Boyd sped up and banked right and upwards, keeping two hands on the control stick. The biplane shook and flexed into the movement with a growling engine.

One of the Red Army biplanes peeled off in pursuit, straining his engine to get above Boyd in the sky.

Come on, Red. You took the bait. Get ready for a surprise.

The Red Army pilot fired a burst from his 7.7mm Vickers machine gun. Boyd executed a barrel roll, corkscrewing away from the bullets. He slowed down and let his attacker overtake him before he pulled the stick back into a vertical climb, feeling his body getting pushed into the seat by the G-forces.

Boyd waited a split second at the peak of his climb before he pushed the control stick forward and dived, delivering a steady burst from the belt-fed Vickers machine gun mounted on the front of his plane. Wind whipped his face and vibrations from the Vickers ran up his arms as he riddled the Red Army biplane with hot lead. The biplane emitted a puff of gray smoke, followed by a black plume. Boyd watched the biplane wheel to the left and limp back to home base.

Boyd’s deadly adrenaline-fueled aerial ballet over the skies of the Crimea completed, he let the damaged biplane go and hurried forward. He caught up with the bombers as they dropped a first load of bombs on the tracks in front of the armored train.

The train’s turreted machine guns and anti-aircraft guns whirled and pumped the sky with bullets as they tried to shoot down the Voisin bombers. The train’s heavy artillery lobbed shells into the advancing White Army just coming into range. The cannon shots were deafening and visibly rocked the train with each salvo fired.

Boyd stayed clear of the machine gun fire and scanned the armored train from above. If Volkov was right, this was Leon Trotsky’s armored car called the “Train of the Chairman of the Revolutionary Military Council of the Republic”.

Boyd watched as the Voisin bombers unload bombs on the track behind Trotsky’s train. The bombs caused enough track damage in front of and behind the armored train to immobilize it.

It was an easy target for the advancing White Army forces.

Operation White Eagle was off to a good start.

From his sky high view, Boyd spied the Trotsky’s Train’s famous elite guard unit pour out of the train and deploy in skirmish order. The soldiers were rolling two armored cars off a flatbed rail car.

Boyd observed the activity on the ground and was happy to be high in the sky, above the noise and smoke; the blood and death. It was peaceful and simpler. Life made more sense to Boyd up here in the sky.

The Voisin bombers made two more runs, dropping bombs on Trotsky’s Train to little effect. Then they veered off to the south and headed for home.Boyd worked his biplane’s control stick and pedals, lowering his altitude before circling back and escorting the bombers to Sevastopol.

Smoke, the roar of engines, and the crash of bombs filled the skies above Trotsky’s Train. Off to his right, two Red fighters materialized out of the smoke and positioned themselves on Boyd’s tail.

Time to get the hell out of here, Jackie Boyd!

The attacking planes revealed themselves as slate gray Spads, a speedy 200 hp French fighter biplane with two Vickers machine guns.

Boyd swiftly cranked back on the control stick with both hands and the biplane hurtled upwards to a vertical position above his attackers. He waited three heart beats absorbing G-forces until the plane almost stalled, then he used his rudder to pivot the biplane one hundred and eighty degrees and executed a perfect hammerhead turn that positioned him above and behind his attackers. He let out his breath, increased the throttle, and leveled the biplane off.

Fly Jackie Boyd Fly!

The Red Army pilot wasn’t fooled. He stuck on Boyd’s tail and delivered two rattling machine gun bursts, ripping bullet holes in a wing. Boyd went into a series of tight, back-and-forth turns, causing the Red Army pilot to overshoot twice.

He won’t miss a third time. I need some help here.

As if reading his mind, Petrov streaked through the smoke spitting hot lead at Boyd’s attacker. Flames leaped from the Red Army pilot’s biplane. Boyd pulled the stick back and streaked forward away from his attacker and out of range of the guns on Trotsky’s Train. He craned his head back in time to see Petrov riddle the biplane with bullets again. The biplane erupted into a mass of flames.

Instead of landing his burning biplane, the Red pilot veered right and accelerated toward Petrov. Boyd watched in horror as the Red Army pilot rammed his flaming biplane into Petrov’s Nieuport. He was close enough to see the wood splinter and hear the screech of steel on steel. The crumpled biplanes locked together, spun around and tumbled to the ground into a burning pile of metal, wood, fabric, wire, and flesh.

Hosanna! … Damn it! … Petrov!

Another Spad jumped on Boyd’s tail. Boyd dipped low over Trotsky’s Train as his attacker raked the tail of Boyd’s biplane with lead. Bullets whined by his head, smashing into the engine and tearing holes in the fabric covered tail and leaving fabric streaming from bullet-torn wings. He increased speed and plunged downward on screeching wings to get away from the chaos, bullets, and smoke in the skies over Trotsky’s Train.

Suddenly, the train’s cannon roared another salvo at the attacking White Army forces. Boyd was too close and cannon’s concussive force slammed into the biplane, turning it sideways and stalling it in midair. He heard the engine sputter as he used all his strength to wrestle with the control stick to stay airborne, the cannon shot ringing in his ears.

The Spad let loose with a long burst of machine gun fire that hit everything except Boyd. The engine cut out and Boyd was in a freefall.

Dead stick landing. Let’s see if you are the best pilot in the world.

He struggled with the control stick and manipulated the pedals to maximize glide and minimize speed. His arm muscles bunched with the strain of keeping the powerless biplane trim. He spied a landing spot as black smoke started pumping out of his engine. He reckoned he was coming in too fast, but didn’t have time to correct his speed as the earth was racing up at him. He pictured his family in Alabama. If he died now, he’d never get to see their faces when he came back rich from flying.

The biplane hit the ground and bounced twice before its wheels bulldozed through the dirt and snow to a stop. The force of the impact threw Boyd forwards and then backwards in the cockpit, straining his back and shoulder muscles as he kept a vice grip on the control stick and gritted his teeth.

Boyd shook his head to get the cobwebs out and scanned his body for any broken bones. Finding none, he used his shoulders to pull himself up and climbed out of the wrecked biplane’s cockpit. His legs shook and his head felt thick. He fell to his knees in the frozen, crusty snow and caught his breath. Then he stumbled toward a stand of pine trees about twenty yards away and fell into a ditch rimmed with brush where the ground unexpectedly dropped off. He rolled on to his back with his breath coming in irregular gasps. He expected to be found shortly by Red Army soldiers.

The top of Trosky’s Train was visible through a web of spidery branches stripped of any leaves. Boyd watched the train huff and puff clouds of ash-filled soot and steam from its smokestack like an evil primordial monster.

He felt drugged with weariness. His squadron was gone. He was on his own on the north side of the armored train.

He could hear rifle fire mixed with the heavier, faster sound of machine guns. As he lay on the cold ground, his head cleared and he realized no one was coming for him.

Boyd pulled himself up and sat on his haunches. Hunger gnawed at his belly. The weather was turning piercingly cold. The sounds of battle grew fainter. Boyd brushed snow off his pants and figured he had a chance if he could wait until night and slip through enemy lines back to the White Army.

& & &

Hours later, as late afternoon slid into dusk, Boyd stretched and slapped his arms across his chest repeatedly to stay warm. Boyd decided it was too cold to wait any longer. He could faintly hear rifle fire to the south, but Trotsky’s Train was eerily quiet with only five of its windows glowing with light.

All was quiet on the north side of the train too. Boyd figured most of the Red Army troops were headed south to fight the attacking White Army.

He bellied up to the top of the ditch and could see his wrecked biplane with both wings snapped in half, looking forlorn in the snow-covered field to his left. On his right, next to the armored train, he noticed someone had parked two automobiles near the repaired train track. As Boyd watched, three men rolled into position near the cars in the growing twilight a small, dual cockpit plane. The men shared a cigarette for a couple of minutes, the glowing tip of the cigarette dancing between them.

Two men started the biplane’s engine and gave the propeller a spin, then returned the way they had come. Boyd figured the men for mechanics, readying the small, dual cockpit biplane for flying. The third man leaned over into the observer cockpit with a six-inch long iron wrench in his hand. He was thick around the middle and had dark hair.

Boyd didn’t hesitate. He took one look around, sprinted and ducked down alongside the first car, a Rolls Royce, with the Tsar’s emblem emblazoned on the driver’s door.

He pulled out his boot knife.

The pudgy mechanic still had his back to Boyd. The biplane’s engine would drown out any sound made by Boyd.

Boyd scooted low around the second car and then ran forward and plunged the razor-sharp steel blade into the middle of the man’s back. He could feel the blade tear through the jacket and slice into soft flesh before cracking against bone. He jerked the knife up and tugged it to the left. A ragged exhale of breath was the only sound the mechanic uttered. His body relaxed and slid forward, falling in a crumpled heap into the observation cockpit he’d been working on. His blood flowed freely and stained the floor of the second cockpit.

That’s for Petrov.

He wiped his knife clean on the dead man’s coat and slipped it back into his boot.

Voices coming from around the corner of the train floated to Boyd’s ears. They sounded close and coming toward him.

He jumped into the pilot cockpit. The engine was primed and the ignition switch was on, so he opened the throttle and grabbed the control stick. Just then, the two other mechanics came around the corner of the train and stared at the biplane performing a shaky jitterbug across the bumpy snow of the partially cleared field.

Chilly wind slapped his face as the biplane sputtered and hopped twice and was soon airborne. Two rifle shots wide of the mark followed Boyd as the aircraft roared into the skies, just clearing the treetops.

He flew north, then circled wide back toward the south and Sevastopol. Boyd took a moment to familiarize himself with the biplane because he’d be landing it in the dark on the Sevastopol airfield. Wire and metal fasteners held the biplane’s wood frame together, covered in green fabric. Someone emblazoned a red star on one side of the biplane. The fuel gauge showed a full tank. The engine purred like a cat. He figured he was flying the collapsible plane from Trotsky’s Train.

Boyd breathed out. It felt good to cheat gravity again and cut off the rest of the world for a moment of peace as the small, open, dual cockpit biplane labored to get altitude. A Russian-made machine-gun with a stick clip was jerry-rigged to the right-side of the pilot’s cockpit. The biplane was sluggish and handled like an oversized bathtub with wings.

Below in the distance, the lights of Trotsky’s Train stabbed the darkness like a beacon in the twilight. The train was like a living, coiled, looming beast, snorting and wheezing clouds of smoke and steam.

Thank you, Comrade Trotsky, for the use of your plane.

Ten minutes of flying placed him over the Red Army soldiers and armored vehicles swarming forward in a ragged line. Glancing ahead in the indifferent light, he could see the White Army was in full retreat with soldiers, tanks, and trucks falling back.

So much for Operation White Eagle.

The sun had set, providing his biplane the cover of darkness. He kept an eye on the star Sirius to help keep him heading south. Soon, sharp, blue stars brightened the darkening sky. A half-moon rose, turning the ground from Boyd’s perspective into a dull silver landscape.

Ahead, Sevastopol was a dark lump sitting low and sprawling along the edge of the dark, glistening waters of the Black Sea. The lights of the city spilled out on the water and glowed an oily black. The harbor swarmed with ship lights of all kinds. From the air, the pinpoints of lights looked like fireflies.

He sensed movement behind him and his heart leaped in his chest. He ducked just as an iron wrench whistled past his head and slammed into the edge of the cockpit opening, sending a shock wave through the biplane.

The mechanic, like a crazy-eyed, blood-soaked ghoul, raised his arm again to deliver another blow with the wrench. Boyd cranked back on the control stick, driving the mechanic back and almost tumbling out of the second cockpit. Boyd trimmed the plane and reached for his broom handle Mauser in his shoulder holster as the mechanic lurched upwards with a grunt, bloody fingers clawing to get a handhold.

He swung the wrench again and Boyd let go of the controls to throw himself sideways in the cockpit so the wrench thudded harmlessly on the seat back.

Down plunged the biplane without a hand on the control stick. As the biplane plummeted, it rocked both men violently from side to side in their cockpits. Boyd extended the Mauser inches from the mechanic’s face and pulled the trigger.

The backside of the mechanic’s skull exploded in a mess of bits of bone, brains, and blood. The mechanic’s body collapsed back onto the cockpit floor of the observation cockpit, followed by the wrench.

Boyd holstered his pistol and grabbed the control stick, righting the aircraft. He blew out forcibly. The cool night breeze carried the coppery smell of blood from the body away from Boyd. A bead of sweat rolled down his forehead from under his leather aviator helmet. He couldn’t remember where he’d lost his gauntlets.

Now stay dead.

Boyd took a deep breath, expanding his chest. Then he pushed the thought of the dead man in the cockpit behind him from his mind and reviewed what he needed to do once he was on the ground.

Twenty minutes later, Boyd had circled the Sevastopol airfield three times in the dark, surprised to find the moonlit airfield deserted. He closed the throttle and landed the craft without incident.

He jogged into the city and pushed his way through the anxious, babbling throngs in the dark streets, struggling to reach the harbor. The darkness ratcheted up the sense of panic and desperation among the people carrying all manner of objects trying to get out of Sevastopol.

Boyd found Dmitry, the Pigeon Master, sliding pigeon cages onto the wagon bed of his horse-drawn cart alone in the alley with an empty pigeon coop.

The sway-backed white horse yoked to Dmitry’s wagon was skin and bones. It looked at Boyd with large, wet eyes and shook its head as if to wipe the image of Boyd from its mind.

“Good. You’re here. We have little time. Everything is set,” said Dmitry. The pipe in his mouth moved with every word. The rich, moist smell of Dmitry’s pipe tobacco was thick in the air around his head like a halo. In the dark, his black eyepatch looked like a hole in his head.

“Load that grain barrel. Then we can leave. I let all my pigeons go except the few I’m bringing with me,” said Dmitry, jerking a thumb toward a squat wooden grain barrel laying against the pigeon coop. Boyd wrestled the barrel on to the wagon.

“Chyorny Pilot!”

Davis Taylor hailed the two men as he came around the corner into the alley. He carried a large, black Webley revolver in his right hand pointed at Boyd. He had a camel-hair coat over his dark worsted wool suit. A matching fedora was on his head. His cravat was a dark crimson color. His heels clicked on the street’s hard surface.

“Followed you from the airfield, Boyd. I was afraid the Chyorny Pilot would not make it back from Operation White Eagle but you never disappoint,” said Taylor.

Taylor’s face was in shadow. All Boyd could see of his face was a big, toothy grin.

“Dusty old pigeons,” said Taylor. He waved his revolver toward the two men, saying, “I’d like your money belt. I’ll be leaving this wretched place soon and need working capital to negotiate passage. You’ve been very industrious selling information to anyone with money. I know you have money. In gold.”

“What about the British Government?” asked Boyd. “Your employer.”

“Alas, I have lost track of my contacts in that capacity and don’t want to arrive at the harbor empty handed, especially if I can’t find my employer. With your money belt, if worse comes to worse, I can buy passage. On the other hand, if I find my colleagues, the money will be a nice bonus for me. Now, hand it over. I don’t want to shoot both of you.”

Boyd figured he had no chance to get his Mauser out before Taylor shot him. Hi eyes darted to the thick shadows across the street and he tensed all his muscles. He took a half-step back. “Hold, right there Boyd. I’ll shoot you and the pigeon man if you move again.”

Dmitry stood silently, puffing his pipe.

“Boyd! The money belt!’ ordered Taylor.

Boyd caught movement behind Taylor and watched Sophia slip around the corner. Her fur coat was open. She took two quick, light steps forward and raised a silver pistol, holding it with two hands. She had her black hair piled on her head, and her pale skin was luminescent in the night air. Her ruby red lips looked black.

She pulled the trigger once, then twice. Taylor stiffened with the impact of each bullet. He half turned toward Sophia, dropping his Webley.

“I say . . .” mumbled Taylor as he joined his Webley on the ground.

Sophia ran forward and picked up the Webley. She shoved it into an inside pocket of her fur coat.

“I need quick money for passage out of Sevastopol. I’ll take your money belt. Now.” She said, pointing the pistol at Boyd.

“How about I give you the French francs you gave me this morning? I have them in my pocket. These francs have value in every civilized spot in the world, you said.”

“Give me the money belt.”

“The French government will pay your passage,” said Boyd.

“No, they won’t because I’m a native Russian. I need to get out of here before the Reds find me. If they find out I was a spy, they’ll torture and kill me,” she shivered.

Dmitry smoked his pipe, watching the interchange like it was a play.

“My money belt is all I have,” said Boyd.

“Hand it over or I’ll drop you both.”

“I’m going to get it. The money isn’t worth our lives,” said Dmitry.

“No!” shouted Boyd.

Dmitry shrugged and reached into a grain bin against the wall of the pigeon coop, and fished around inside before pulling out a tan canvas money belt.

“Dmitry, you bastard!” seethed Boyd.

“You’ll thank me later,” said Dmitry. He limped over to Sophia and handed her the money belt. She weighed it in her slim white hand for a moment and pulled a thin smile.

“Goodbye and good luck,” she said. Sophia walked backwards, retracing her steps, keeping the two men covered with her pistol.

She vanished around the corner.

The two men looked at each other. Dmitry grinned.

The old man opened the grain bin on the wagon and fished his hand through the loose grain. He pulled out another money belt and winked at Boyd.

“She’ll be surprised when she discovers my old socks filled with pebbles, sand, and newspaper in the money belt I gave her,” said Dmitry. “Seventy – thirty split of the money still? I’m not greedy.”

“Agreed. Your thirty percent includes a boat ride for me away from here.” Boyd cinched the money belt around his flat waist and covered it with his shirt and leather jacket.

“My brother in-law, the fisherman, keeps his boat a couple miles from here outside the harbor in a small inlet. He’s waiting for us.”

Dmitry stiffly pulled himself up into the wagon’s seat. He pulled out a small bag of tobacco, stuffed his pipe, and lit it. The flame bending down each time he breathed in.

“Hop in the back. Keep my pigeons company.”

He buttoned his long gray wool jacket and picked up the reins. He made a clucking sound with his tongue, and the wagon lurched as the old nag plodded forward.

The old man cocked his head toward Boyd sitting in the wagon bed with his legs stretched out in front of him among the cooing pigeons.

“I hear Constantinople is nice.”

& & &

Dawn stretched its rosy fingers across the sky, and light shimmered from a single window of Trotsky’s Train. It looked like the single, unblinking eye of a massive black beast.

The wind blew Comrade Trotsky’s thick, dark hair over his round glasses as he stood on the train platform outside his illuminated armored-plated office car. Trotsky’s Train was spewing steam and spitting ash. Its hot box, laced with coal, glowed red.

“What are your orders, Comrade, sir? asked the officer in the red leather uniform of Trotsky’s elite Red Guard unit.

“Continue advancing troops and equipment south. Attack and secure Sevastopol and its harbor. Those are my orders, captain. We have an empire to win!”

The captain snapped a salute.

The train whistle blew and sounded harsh and brittle in the cold, dry air. Trotsky’s Train flexed its iron muscles, slowly overcame inertia and trundled down the steel track heading west with the rising sun on its long snake-like back.

* * * * THE END * * * *

Copyright R. K. Olson 2025