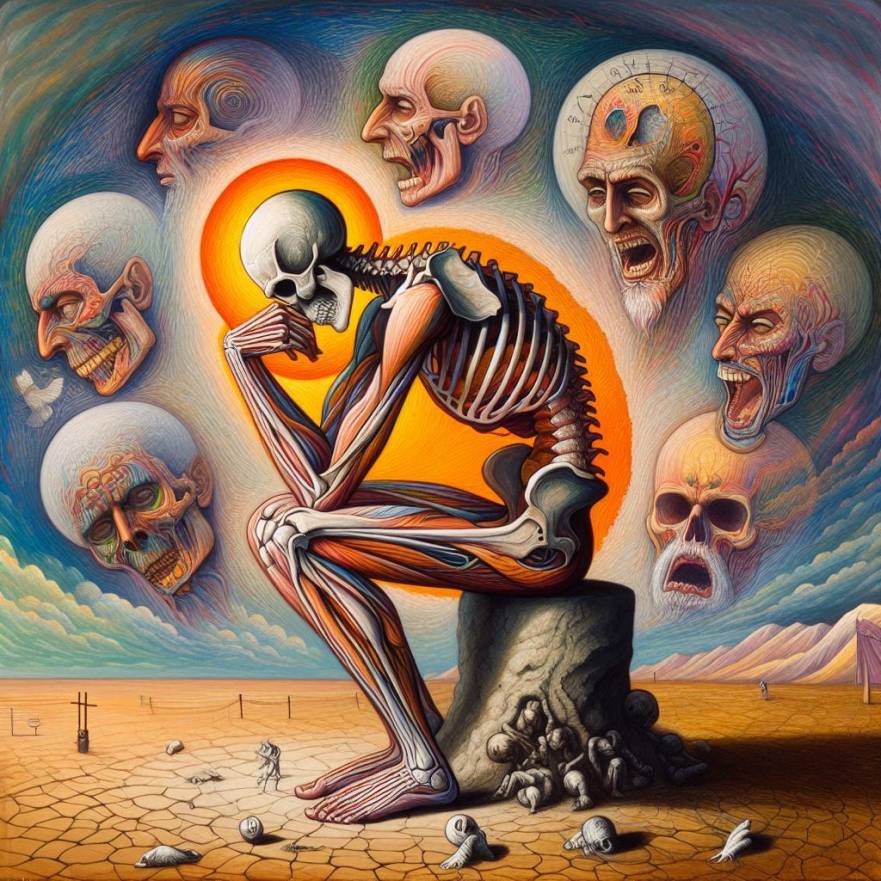

Decay by Titoxz

Decay by Titoxz

In my earliest memories, everything is quiet. Not peaceful, but subdued, as if the world is holding its breath, waiting for some noise or catastrophe that never quite arrives. Even then, I sensed a tension in living—a tension I would only begin to articulate years later, through reading, through argument, through endless cycles of disappointment. It seems the reasons for my life’s trajectory—the estrangement from people, the burying of hope—were always there, embedded like seeds in the very streets I walked, in the fading sunlight over sagging rooftops. And as I sit here now, sifting through the fragments of my history, I see three great strands that led me to this vantage point of utter mistrust: my love for Elena, my time in the academic sphere, and my final break with the only friend I had ever trusted, Igor.

I am Victor Mercer. And what follows is not a confession but a record, a kind of post-mortem on optimism itself. I find myself in a cramped room overlooking a haze of skyscrapers and battered buildings. I have come to understand human society as a monstrous organism, feeding on illusions of progress, devouring authenticity. This document, however lengthy, stands as my last honest attempt to outline the slow, fateful sequence that turned me against humanity—if, in fact, I was ever truly on its side to begin with.

PART I

The industrial town where I was born lingered in a state of perpetual twilight. The factories that once promised decent wages emitted plumes of gray smoke into a sky that seemed to darken each season. The local shops stood half-empty, their owners peering out with weary resignation and the occasional forced grin. My father worked as a shift supervisor at one of those plants, leading crews of exhausted men who dreaded pay cuts and layoffs. He talked little about hope or ambition, preferring to focus on weekly tasks: “Keep your head down. Don’t give them an excuse to let you go,” was his general wisdom.

My mother, by contrast, clung to a shred of idealism. She taught high school literature, introducing restless teens to the resonance of words. She believed that reading could break cycles, that a single poem could uplift a battered spirit. I loved her for that faith, but even in childhood, I sensed an inevitable letdown. Her stories of redemption—Dickens, Dickens everywhere—warred with the quiet despair I saw on the faces of our neighbors, with the gloom settling in the factories’ corridors. She lost more and more battles every year to standardized tests, indifferent administrations, and students too jaded to care.

I disliked my hometown not because it was poor or dirty, but because it felt resigned. Even in childhood, I sensed the weight of its inertia: the adults around me seemed paralyzed by forces they claimed were beyond their control. Jobs vanished. Pensions evaporated. Families scraped by. “That’s life,” they would say, as if no possibility existed to alter the course of their destiny. I bristled against that fatalism, uncertain of what would replace it but sure it was no way to live.

Growing up, I read constantly, huddling over every volume I could borrow. At eleven, I tried reading “Crime and Punishment,” far beyond my ability, but something in Dostoevsky’s overarching guilt-fueled introspections appealed to me, even if I couldn’t decode all the sentences. This sense of displacement, of tension, and of moral crisis became my everyday background. And from it, ironically enough, sprang the only friendship that truly mattered to me in those years: Igor Kuznetsov.

Igor lived four blocks away. His family was in a similar predicament—his father had lost a managerial job, ended up driving deliveries for a distribution center. His mother was too ill to work, and government assistance rarely sufficed. Igor didn’t complain much; we simply recognized, on a wordless level, that our families walked parallel tightropes over a gray void of poverty.

We first spoke in the school library. I must have been just shy of thirteen. I noticed him reading a battered textbook on world history, scribbling notes in the margins. He seemed so intent that I wondered what possessed that level of concentration. I approached, not sure what to say, and ended up babbling something about how pointless I found our social studies class. He glanced up, his bright, inquisitive eyes flicking over me. Then, suddenly, he snorted a laugh and said, “We’re the last ones who believe there’s something beyond this place, aren’t we?”

Strange as it sounds, that single comment sparked the closeness between us. We were children, yet we carried an adult’s cynicism about our decaying environment. We also shared a grain of ambition, though it manifested differently in each of us. We would stay after school, reading in hushed corners while janitors vacuumed. Igor brought me pamphlets about successful entrepreneurs, about men who overcame financial turmoil. He said we could escape, too, if we found a strategy. I was more comfortable with Plato, Shakespeare, Dostoevsky—tomes that explored the darker folds of the soul. “Ideas shape men,” I’d say. “What good is success if you end up the same as those corporate drones?”

We formed a kind of secret alliance, though no oath was sworn. We recognized each other as two minds unwilling to accept our parents’ fate. We devoured all the knowledge that came our way, from tattered library books to late-night documentaries on the local public station. Our debates were fervent, sometimes playful, sometimes intense. Often, we parted ways late in the evening, only to resume the conversation the next morning.

By high school’s latter years, our synergy had shifted toward friendly competition, each daring the other to excel. When college applications approached, we scoured every scholarship. I recall long nights in Igor’s cramped bedroom, the walls plastered with newspaper clippings about economic trends, social revolutions, educational reforms. He told me, “Success is a game. Either you figure out the rules, or you get left behind.”

I retorted that the real issue was the game itself, that it exploited people and bent them to the will of invisible powers—capital, policy, empty rhetoric. This difference only grew. Igor wanted to harness the system. I wanted to expose its fundamental sickness. Still, at that point, we didn’t see these stances as contradictory. We thought we could remain friends forever, balancing each other out. In that battered town, we needed each other’s presence—allies forging a path out of the gloom.

Upon graduation, we slightly parted. I was accepted to a state university, majoring in philosophy and critical theory. Igor won a partial scholarship in economics at the same institution but enrolled in the integrated business track. We were thrilled to be going together—two small-town boys with big minds, diving into the unknown. The plan was that we’d remain roommates or at least live close enough to keep fueling each other’s ambition. We left behind parents who gave us tired well-wishes and hobbled moralities, certain we’d conquer the world where they had failed.

PART II

University life felt like another planet compared to our rundown hometown. The sprawling campus, with its manicured lawns and stone buildings, swarmed with restless ambition. Everyone seemed fixated on “networking” or “career-building,” words that meant little to me but everything to them. I was immediately intoxicated by the library’s vastness, by the array of journals devoted to critical theory, sociology, and philosophy. Within those walls, I discovered an entire canon dedicated to dissecting the illusions of modern life—thinkers who argued that capitalism, religion, the justice system, indeed every social institution, was a scaffold of deception.

Igor, meanwhile, gravitated to the business and economics departments, enthralled by advanced seminars on market analytics and policy manipulation. At first, we tried to maintain our old routine, meeting regularly for cheap cafeteria meals. We’d bemoan the superficial parties on campus, the fraternities fueled by beer-laden silhouettes of brotherhood, the clubs that worshipped bullet-point resumes like holy scriptures.

But subtle tension crept in. Igor’s language shifted. He began speaking excitedly of data-driven strategies, corporate expansions, the potential for “ethical marketing,” as though such a phrase was not contradictory. I, on the other hand, dove into Adorno, Horkheimer, Marcuse—names that hammered home what I already suspected: that capitalism was an unholy machine that commodified everything, from love to education, from justice to spiritual longing.

Sometimes, in the lounge, Igor and I would have friendly spats over coffee. “You see illusions everywhere,” he’d say, half exasperated. “But illusions can be leveraged. If we understand them, we can guide them—maybe even for good.”

I’d narrow my eyes. “Exploitation can’t be sanitized. And if you sanitize it, you’re just making it more palatable for the masses.”

He’d shrug, unconvinced. Our dynamic held, but I sensed we were no longer two kids huddling in a dilapidated library corner. We were on diverging paths—he on a mission to conquer, I on a mission to expose. Yet we still believed we could coexist; we were, after all, the last remnants of each other’s childhood sense of belonging.

Midway through my sophomore year, I wrote a paper titled “The Manufactured Self: Capital, Cognition, and the Illusion of Autonomy.” Fueled by late-night reading sessions and a mounting disgust at the corporate infiltration of the human psyche, I poured every ounce of my frustration into that piece. A tenured professor took notice, commending my ability to integrate philosophy, sociology, and critical theory into one searing indictment. He invited me to present at a small departmental colloquium.

Igor attended out of loyalty. I remember standing before a sparse audience of faculty and graduate students, heart racing, as I outlined how consumer culture manipulated desire itself—how entire legal structures, religious institutions, even educational frameworks were subservient to profit. The Q&A that followed was intense. Some called me too absolute. Others found my condemnation refreshing. Igor raised his hand:

“Victor, is there truly no way to repurpose these forces for the collective good? Couldn’t we redirect consumerism, say, to improve infrastructure, or use corporate sponsorships to elevate underfunded communities?”

His question didn’t surprise me. “These structures inherently rely on exploitation,” I replied, steel in my voice. “They can shift their target, but the principle remains: someone or something is being commodified. The so-called ‘collective good’ becomes another marketing angle.”

A flicker of hurt passed across his face, but he nodded graciously. We parted ways that evening with an uneasy mutual respect. In that moment, I realized how deeply we were drifting. Yet a part of me still clung to our friendship as if it were an anchor in a raging sea.

Despite ideological rifts, Igor and I shared an apartment near campus. We still laughed about how incompetent we were at cooking, how ridiculous we found the endless round of campus “leadership seminars.” We also reminisced about our hometown, recalling the sagging rooftops and factory smoke with a mix of disdain and nostalgia.

“We escaped,” Igor said once, stirring watery spaghetti sauce in a battered pot. “I, for one, am never going back.”

I nodded, though with less certainty. My memory was riddled with the paternal litany of “keep your head down,” the maternal hope that a single poem could save a person. The older I got, the more I questioned whether true escape meant physically leaving a place or intellectually renouncing its fabrications. I had done the latter thoroughly enough, but physically? My father was still there, my mother still fighting an unwinnable battle in her failing school district. Could I ever truly leave that behind?

Such questions weighed on me, but I rarely voiced them. Igor was forging onward, and I needed to keep pace, if only to hold onto the one connection that had defined my adolescence.

PART III

It was during my junior year that I found a deeper sanctuary in critical theory. I was accepted into an advanced seminar led by a professor enthralled with the Frankfurt School. He assigned readings that systematically dismantled every institution, from the commodification of art to the infiltration of capitalist logic into the justice system. I began outlining what would become my doctoral dissertation: “Instrumental Reason and the Commodification of Lived Experience.” Each chapter would eviscerate a core institution: education warped by standardized testing and corporate grants, justice sold to the highest bidder through privatized prisons and exploitative bail fees, healthcare strangled by price-gouging and labyrinthine insurance networks, and religion turned into a spectacle of mega-church branding and consumerist salvation.

I was ecstatic to find an intellectual tradition that validated my deepest suspicions. Yet, for all my newfound clarity, I felt a pang of loneliness. Was there no one else at this university who grasped the sheer magnitude of the doom that governed us?

Then I met Elena.

She approached me after I guest-lectured in a sociology course on how corporate sponsorships eroded public-school autonomy. I’d been railing against the infiltration of marketing into the classroom—where brand logos loomed over assemblies, and standardized testing was a cash cow for big corporations. As the room emptied, Elena lingered, flipping through her notes with laser-like focus.

“That was interesting,” she said, voice poised and calm. “But you missed an entire demographic dimension—how race and class interplay with corporate meddling. Especially in impoverished districts.”

She introduced herself as Elena Michaels, a transfer student in sociology. She had done field research in underfunded schools across multiple states. Over coffee in a musty lounge, I learned she referred to modern society as a “viral system”: a living, self-propagating entity that adapts to preserve power structures. The metaphor was startling. And in that metaphor, I found a kindred intellect—someone who recognized the monstrous organism beneath the surface.

We talked until closing time, delving into the moral bankruptcy of religious institutions that sold salvation for tithes, the travesty of the for-profit prison system that turned human suffering into business. She was as radical as I was, yet there was a hidden warmth in her voice, a flicker of compassion that refused to die. She contended that pockets of genuine empathy still existed, even under the weight of the corporate machine. Unlike me, she believed these pockets mattered.

The more we talked, the more I found myself drawn in. That night, alone in my apartment, I replayed our conversation, struck by how she perceived the same grim truths I did—yet refused to slide into despair.

In those days, I was beginning my lectures as a visiting professor, invited to teach an upper-level seminar on critical theory. I threw myself into course preparation, weaving together Adorno, Marcuse, Foucault, and other thinkers who saw the rot in modern institutions. My students seemed perplexed at first. They were used to mild overviews, not a professor who forcibly connected the reading to our city’s structures: the synergy of media, consumer desire, and corporate greed. A small handful responded enthusiastically, while the rest were uneasy. But Elena would attend whenever she could, sliding into a seat at the back, listening with that keen, unflinching stare. I found myself—surprisingly—trying to impress her, pushing my arguments even further, forging links between the emptiness of curated social media and the grand illusions of late capitalism.

It might sound trivial, but those lectures were some of the best moments of my life. I felt a glimmer of hope that my ideas could reshape something, that the myths stifling us could be undone through tenacious critique. Elena and I debated my interpretations afterward, often over coffee in the musty on-campus café. Sometimes she agreed, sometimes she shook her head—but either way, the conversation felt electric.

Igor was traveling abroad that semester for a special program, so he had no chance to meet Elena right away. By the time he returned, Elena and I were distinctly more than colleagues. We grew close amid late-night debates, discovering we had both come from fractured communities—my factory-town cynicism mirrored her experiences of dysfunctional institutions. Over a short span, our connection turned personal, though we both disdained the usual “romantic” language. Our bond thrived on intellectual synergy, shared disillusionment, raw honesty. For the first time, my solitary misanthropy felt tempered by someone who understood it but still dared to see glimmers of compassion in the wreckage.

When Igor came back and discovered Elena in our apartment, reading my drafts while leaning against my shoulder, he lifted an eyebrow. At first, he was cordial. He recognized a familiar spark in her critique of modern institutions. But soon he seemed more distant. Perhaps the dynamic between Elena and me unsettled him: we used to spend hours, just the two of us, dissecting the world. Now I had someone else to share those debates, and Igor recognized Elena might challenge him even more fiercely than I did.

I recall one evening when the three of us half-dined on leftover noodles, conversation turning to how corporations manipulate identity. Igor insisted that, in a globalized world, harnessing those manipulative strategies might allow for beneficial policy changes—like subtle ways to encourage better educational funding. Elena calmly dismissed that argument. “You’re still relying on top-down control,” she said, “just hoping it’ll be used benevolently. And history tells us that’s naive.”

Igor looked wounded for a split second, then rallied. “It’s only naive if you assume no one decent exists in power.”

Elena arched a brow. “Tell me where decency ends and ambition takes over.”

I watched, not entirely comfortable. Igor was still my one true friend. Elena was the woman who illuminated corners of my worldview I hadn’t dared explore. I prayed, silently, that we could maintain some equilibrium. But tensions rose whenever Elena’s unyielding logic clashed with Igor’s pragmatic streak.

PART IV

My acceptance into a doctoral program felt like destiny. I dove headlong into writing “Instrumental Reason and the Commodification of Human Experience,” refining each chapter until it resembled a scalpel slicing into the heart of consumer culture. The premise was simple and damning: modern capitalism corrals human potential, branding and selling every aspect of existence from intimacy to leisure. I analyzed how advertising distorts identity, how social media fosters illusions of connection, how the pursuit of profit infiltrates even moral values. On paper, it was a systematic condemnation. In spirit, it captured a lifetime of raw anger.

Meanwhile, Igor’s star rose in his own domain. He finished his master’s in economics and pivoted to a management track. Recruited by the university’s business consultancy department, he engaged with corporations that sought new ways to interpret data about consumer behavior. I teased him for fraternizing with the enemy, but he laughed, claiming that it was all a strategy. “Better to understand the game from the inside,” he’d say. “We can’t just wave a wand and fix things from some ivory tower.”

Elena, for her part, joined the sociology department as a research fellow. She conducted field studies in struggling neighborhoods, collecting evidence of how local politics, corporate sponsorships, and bureaucratic inertia created cyclical poverty. We’d convene at day’s end, exhausted, exchanging notes and theoretical insights. Sometimes we attempted to share them with Igor, but his interest was sporadic. He was busier with job fairs, corporate mixers, forging a new identity that steadily edged him away from academic critique.

When I finally defended the dissertation, it felt like entering a war zone—my thesis was a deliberate broadside against every pillar of society. The academic panel comprised six professors, some of whom were sympathetic to critical theory, others who found my arguments too incendiary.

I stood at the head of that narrow conference table, delivering a scorching indictment of how civilization manages to buy and sell even the deepest parts of our humanity—hope, love, identity itself. My voice wavered at first, but soon a grim resolve took hold, pushing aside my initial tremors. I wasn’t just challenging a flawed system; I was stripping away the glossy facade that kept everyone in silent compliance. I was revealing, with every fervent word, that the emperor wore no clothes—that society was, at its very core, a monstrous organism sustained by systematic deceit.

Questions rained down afterward—some lauding my analysis, others criticizing me for offering no solutions. “Your approach is purely polemical,” one professor challenged. “Where is the blueprint for reform?”

I stared at him, unflinching. “When a system has deteriorated this severely, superficial reforms are no better than painting over mold. I have no intention of peddling hollow reassurances or short-term fixes. My purpose is to diagnose the underlying pathology in all its stark reality.”

Tension bristled in the room. In the end, they passed me with distinction, though the air felt heavy with unspoken judgment. Igor lurked at the back. Elena was there too, her hand pressed over her mouth in a gesture of relief as the committee announced their decision. I locked eyes with her, feeling a fleeting joy that she had witnessed my triumph.

Igor approached me once the formalities ended. “Congratulations, Doctor Mercer,” he said, voice measured. “Though it’s bleak, isn’t it? You paint humanity as an unwitting puppet.”

I gave a casual shrug. “Oh, absolutely—smoke and mirrors everywhere. If you’ve got a bright side, do enlighten me, because my supply of rainbows and unicorns is running dangerously low.”

Igor gave a small grin, though his eyes were unreadable. “Some of us still think we can steer these carnival acts in a better direction. We can’t all be prophets of the apocalypse, right?”

A retort burned on my tongue, but Elena touched my arm gently. The warmth of her hand diffused my anger, and I turned to talk with the panel instead, letting the moment pass. Later that night, Elena and I walked. She slipped her hand into mine, a gesture of quiet solidarity. My chest felt so tight with emotion that I thought I would burst, but again, I said nothing about love. I merely squeezed her hand, silently grateful that I had found someone who understood my scorn without being consumed by it.

PART V

When Elena and I first decided to share an apartment near the university, neither of us wanted to call it “moving in together,” as if that phrase carried a weight we weren’t ready to acknowledge. Yet from the moment we unlocked the door and stepped onto the threadbare carpet, something in the air felt different—a quiet, fragile harmony taking shape between boxes of books and mismatched cookware.

Our mornings often began in near silence, with the sun peeking through the thin curtains. She’d wake earlier, reading notes for her sociology fieldwork, sometimes scribbling observations in the margins with a pen she held in a loose, thoughtful grip. I’d watch from across the table, coffee in hand, as her face shifted subtly—absorbed, determined, a hint of melancholy at the edges. These small details drew me in with an intensity I couldn’t name.

Evenings brought us back to that tiny living room, a couple of lamps casting pale circles on the walls. We’d cook simple meals—rice, lentils, vegetable stir-fries—often losing track of time in long discussions about everything we’d encountered that day. She had a knack for pulling real stories from the chaos of data: families scraping by on dwindling wages, children finding fragile comfort in run-down community centers. Whenever I spun off into my diatribes about corporate schemes or commodified fantasies, she’d tilt her head, smile faintly, and point out some flicker of kindness she’d witnessed—a neighbor sharing groceries, a teacher guiding a struggling student.

I questioned her insistence that these small mercies amounted to anything in the face of such relentless exploitation. Yet she refused to concede, maintaining that if we dismissed all gestures of care, we would be no different from the systems we condemned. Her words unsettled me, stirring a reluctant sense of hope I was never willing to admit.

Outside our apartment, the university bustled with its usual self-importance: students clambering for internships, administrators hawking leadership seminars, the glossy brochures promising futures none of us truly believed in. But at home—with Elena reading on the couch or debating policy over leftover pasta—there was a hush in my thoughts that felt safer, brighter. A subtle pulse of warmth undercut my usual bitterness.

Neither of us put a name to these feelings. We openly scoffed at popular notions of romance—corporate gifts, sappy greetings, social media declarations. Yet in the half-darkness of our modest living room, words often felt superfluous anyway. A glance from her across the rim of a teacup, or the quick meeting of our eyes when some new thought sparked, carried more than any grandiose confession.

On difficult days, when my anger at the system flared into outright despair, she would rest a hand on my shoulder, reminding me that cynicism alone couldn’t light the way out. In those moments, I allowed myself a fleeting calm I rarely felt elsewhere. I suspect she believed that once empathy was forsaken, we’d be doomed to replicate the very power plays we despised. Each time she said so, something in me softened, though I kept that softness hidden behind dry logic and half-formed retorts.

We lived like that for a while—balancing each other’s extremes, shaping our days around research papers, cheap groceries, and long, impassioned talks. If anyone had asked what bound us together, neither Elena nor I would have given a neat answer. Yet in that cramped apartment, I found a kind of closeness that hovered somewhere between serenity and urgency, always alive in the way she challenged me, and in the hush that followed when all that needed saying was said.

During this period, Igor’s visits grew sporadic. He’d show up for coffee, always on his way to some seminar or business conference. He recounted how corporations used advanced analytics to sway public opinion, sometimes with micro-targeted campaigns. “It’s remarkable what you can do with data,” he remarked once, referencing how marketing teams learn consumers’ moods and vulnerabilities. I asked if these manipulations bothered him. He shrugged, implying that it was simply the new reality, a tool that could be turned beneficial if men of conscience took the reins. “Would you rather it be left in the hands of the unscrupulous?”

Elena sighed, meeting my glance. We recognized this conversation was going nowhere. Igor, who once shared our near-militant wariness of corporate influence, now spoke the language of adaptation and exploitation. We parted ways that evening with forced smiles. I remember thinking how easily time unravels once-close ties, how the plywood scaffolding of childhood friendship might collapse when confronted with adult ambitions.

Not long after my dissertation received its modest academic release, Elena began complaining of sharp pains in her stomach. She blamed stress at first. Her fieldwork had taken her to neglected neighborhoods where she saw, day by day, how corporate interests gnawed at the fragile remains of community life. But the pains deepened, until she conceded to a hospital visit.

The examination room was small and without character, a box of white walls, pale green linoleum flooring, and a paper-covered table where Elena now sat. The doctor stood before us, his face composed into what I imagined was a practiced expression of professional sympathy. When he spoke the words—advanced pancreatic cancer—they seemed to hang suspended in the air between us, not quite reaching us at first, as if the fluorescent lights and antiseptic smell formed a barrier that such terrible news could not immediately penetrate.

I watched Elena’s face. Throughout our time together, I had cataloged her expressions with the devotion of a collector: the slight furrow between her brows when she concentrated, the way her mouth would twist to one side when she was skeptical, the rare, luminous smile that transformed her entire countenance when something genuinely delighted her. Now I witnessed something entirely new—a kind of stillness that seemed to come from deep within her. She blinked once, slowly, her dark eyes absorbing the doctor’s words without visible reaction. My hand found hers, and I was struck by how cool her fingers felt against my palm, how I could trace the delicate architecture of bones beneath her skin. My own body betrayed me—sweat gathered at my temples and along my hairline, my heart hammered against my ribs with such force that I wondered if the others could hear it. The doctor continued speaking, his voice a distant drone about stages and metastasis and survival rates, but these words seemed to belong to another world entirely, one governed by statistics and probability rather than the simple, devastating fact that Elena was dying.

In the days that followed, we moved through a landscape of sterile corridors and consultation rooms, where different specialists outlined our options with varying degrees of compassion. Chemotherapy, with its uncertain benefits and guaranteed suffering. Surgery, perhaps, though the cancer had already spread beyond the boundaries where a surgeon’s knife might make a difference. Clinical trials for which Elena might not qualify. Each possibility was presented with careful phrases that neither promised too much nor extinguished hope entirely. I found myself studying these doctors and nurses as they spoke, noting how they maintained eye contact for precisely the right duration, how they leaned forward just enough to convey engagement without intrusion. I wondered if they practiced these gestures in front of mirrors or if they came naturally after years of delivering such news. Elena listened to them all with the same quiet attention she might give to a lecture or a difficult passage in a book. She asked practical questions in a steady voice while I sat beside her, my anger at the entire medical establishment rising like bile in my throat. Not because they had failed her—though they had, we all had—but because they offered the illusion of choice when in reality there was none. When Elena decided to try the chemotherapy, I drove her to the hospital for the first treatment, watching as they inserted the IV into her arm, the clear liquid flowing into her veins like some colorless poison. That night, as she shivered beneath two blankets, her body rebelling against the chemicals meant to save her, I held her hand and felt, for the first time in my adult life, utterly helpless. No book I had read, no theory I had mastered, no argument I had constructed, offered any defense against the enemy that had taken up residence in her body.

One evening, after a particularly difficult day when the nausea had finally subsided enough for her to sip some broth, Elena woke suddenly from a restless sleep. Her hair, damp with sweat, clung to her forehead, and her eyes, when they found mine, held a clarity that seemed almost supernatural given her physical state. Her lips, cracked and pale, curved into what might have been a smile. “There’s something almost poetic about it,” she whispered, her voice rough from disuse. “I’ve spent so long watching systems break down, communities fall apart, institutions fail. Now my body’s following the same pattern. It’s like I’m living out my own research.” She attempted a small laugh, which dissolved into a wince of pain. I reached for the cup of water on the bedside table, held the straw to her lips, watched as she took a careful sip. I wanted to contradict her, to insist that her body was nothing like the broken systems we had studied together, that she was not a metaphor or a case study but a woman I could not bear to lose. But the words wouldn’t come. To offer false reassurance would have been a betrayal of everything we had shared, every conversation built on our mutual recognition of hard truths.

Instead, I placed my palm against her forehead, feeling the heat of her skin, the fragile dome of her skull beneath my hand. Her eyes closed at my touch, her breath evening out slightly. The room was quiet except for the soft hum of the machines monitoring her vital signs and the occasional footsteps passing in the hallway beyond. Outside the window, darkness had fallen, transforming the glass into a mirror that reflected our diminished figures: Elena in the narrow bed, her body now a landscape of sharp angles and hollows; myself in the chair pulled close beside her, hunched forward as if physical proximity might somehow bridge the gulf that was widening between us. I had always prided myself on my capacity to see through pretense, to recognize the underlying structures of deception that governed most human interactions. Now that clarity felt like a curse. I could not pretend that Elena would recover, could not wrap her in comforting lies about miracle treatments or statistical outliers. All I could offer was my presence, my hand against her skin, my silent acknowledgment of her pain. And in that moment, it seemed both the least and the most I had ever given anyone.

The weeks that followed took on a dreamlike quality, as if time itself had become elastic. Hospital corridors stretched endlessly before me; the journey from the parking lot to Elena’s room felt like crossing a vast desert. The smell of antiseptic no longer registered; it had become as natural to me as the scent of our apartment. I learned the rhythms of the ward—which nurses were generous with pain medication, which doctors spoke plainly rather than hiding behind euphemisms. I became fluent in a new language of blood counts and tumor markers, of palliative versus curative care.

Through it all, Elena maintained a strange serenity that both comforted and unnerved me. She insisted on reading when she had the energy, propped up against pillows, her fingers turning pages with deliberate care. Sometimes she asked me to read to her, and I would recite passages from novels we had discussed in healthier days, my voice steady even as my heart constricted. In those hours, watching the light shift across her face, noting how the illness had sharpened her features into a kind of austere beauty, I understood something that had eluded me before: that love was not an abstraction or a social construct or an evolutionary adaptation, but a specific pain located somewhere beneath the ribs, a physical ache that no amount of intellectual distance could alleviate. And though I never spoke the word aloud—we had both been too wary of such declarations—I felt its weight in every gesture, every small act of care, every moment of silence we shared as the days grew shorter and Elena’s strength ebbed like a tide going out.

On the final night, I sat beside Elena’s bed in a kind of vigil, my hand wrapped around hers as if this tenuous physical connection might somehow anchor her to the world. The hospital room had become familiar territory—the particular way shadows gathered in the corners, the soft mechanical hum that never ceased, the antiseptic smell that had ceased to register as foreign. Throughout the evening, her breathing had grown increasingly shallow, each inhalation a labor that seemed to require all her remaining strength. I found myself counting the seconds between breaths, as if this vigilance might somehow ward off the inevitable.

Then, sometime after midnight, the rhythm faltered. Her breathing slowed, then paused, then stopped altogether. The monitor beside the bed registered the change with a single, sustained tone that seemed to fill the room entirely. I sat motionless, still clutching her hand, unable to accept what had happened despite having anticipated it for weeks. Nurses appeared in the doorway, then moved around me with practiced efficiency, speaking in hushed tones that suggested respect rather than urgency. One of them touched my shoulder gently, perhaps urging me to release Elena’s hand, but I couldn’t loosen my grip. It was as if some primitive part of my brain believed that as long as I maintained this connection, she wasn’t truly gone.

“Sir,” the nurse said, her voice gentle but firm. “Sir, I’m so sorry.”

I looked up at her face, composed into an expression of professional sympathy, and felt something break loose inside my chest. A sound escaped me—not quite a sob, not quite a word—a raw, animal noise that seemed to come from somewhere beyond conscious thought. The nurse nodded as if she understood, as if she had heard this sound before from others sitting where I sat now. She didn’t rush me or offer platitudes. She simply waited while I struggled to gather myself, to remember how to exist in a world where Elena no longer drew breath.

In the days that followed, I moved through the necessary arrangements as if following a script written by someone else. I chose a simple pine coffin, arranged for a modest service at a non-denominational chapel, selected an unadorned plot in a cemetery on the edge of the city. Elena had always disdained excess, had spoken with particular contempt about the funeral industry’s exploitation of grief. I would not betray her values now by surrendering to the commercial apparatus of mourning.

The service itself passed in a blur. A small gathering of colleagues and friends occupied the front rows of the chapel, their faces solemn and uncertain. A few of Elena’s research subjects had come—families from the neighborhoods where she had conducted her fieldwork, their presence a testament to the connections she had formed beyond the academic sphere. Someone played a recording of Bach, the spare, mathematical beauty of the music filling the space between awkward eulogies. I sat in the front row, aware of eyes upon me, of expectations that I might stand and speak, might offer some summation of who Elena had been and what she had meant. But I remained silent. Any words I might have offered seemed inadequate, a reduction of her complexity to a series of anecdotes or traits.

At the graveside, I watched as they lowered her coffin into the earth. The sound of soil hitting the lid of the casket was muffled and intimate. Each thud sent a shudder through me, as if I were being struck directly. My throat ached with all that remained unsaid between us—not just in her final days, when words had become precious and rare, but throughout our time together. I had never told her, in so many words, that I loved her. I had shown it in a thousand small ways—in the books I selected for her, in the meals I prepared, in the way I held her when nightmares woke her—but I had never given her the simple gift of that declaration.

Igor sent a brief note from overseas, expressing formal regret at Elena’s passing and at his inability to attend the service. The message was typed, not handwritten, and signed with a digital signature that suggested it had been drafted by an assistant. I folded the paper carefully and placed it in a drawer, unable to summon either anger or forgiveness for this final evidence of how far we had drifted apart.

In the weeks that followed, the rhythm of the city became almost unbearable. The ordinary sounds of life continuing—garbage trucks in the alley behind our apartment building, children shouting in the park across the street, the constant drone of traffic—felt like a mockery of my loss. I watched from my window as anonymous figures hurried to work or school or home, their faces illuminated by the blue glow of their phones, and felt a kind of vertigo, as if I were observing a species to which I no longer belonged. The world’s indifference to Elena’s absence seemed both cruel and incomprehensible. Each morning brought the same routines, the same casual movements of strangers who knew nothing of what had been extinguished, and I found myself increasingly alienated from this callous continuity, this refusal of the universe to acknowledge that something essential had vanished from it.

I tried, once or twice, to return to my academic work. I opened the files on my computer, stared at the familiar paragraphs of critique and analysis, but the words seemed to belong to another man, one whose certainties had not yet been shattered by loss. Every margin note in Elena’s handwriting, every underlined passage that had sparked our debates, was now a reminder of her absence. I would find myself staring at her neat script until the letters blurred, then close the file without having accomplished anything.

The apartment itself became both sanctuary and prison. I moved through its rooms like a ghost, touching the objects that had been hers—books with dog-eared pages, a mug with a chip in the handle that she had refused to discard, the woolen scarf she wore on cold mornings. One evening, as I was sorting through a box of her papers, I found a single strand of her hair caught in the weave of that scarf. It was long and dark against the gray wool, unmistakably hers. I held it up to the light, this fragile filament that had once been part of her living body, and something inside me finally gave way.

I sank to the floor, clutching the scarf to my chest, and wept as I had not allowed myself to weep at the hospital or the funeral. These were not the dignified tears of public grieving but something wilder and more primitive—great, heaving sobs that seemed to rise from the very core of my being. I cried until my throat was raw, until my eyes burned, until my body ached with the effort of it. All the intellectual armor I had constructed over years of study, all the careful cynicism I had cultivated as a defense against disappointment, crumbled in the face of this elemental grief.

When at last the tears subsided, I remained on the floor, too exhausted to move. Outside, darkness had fallen, and the windows reflected the faint glow of streetlights and neon signs. In that dim mirror, I caught a glimpse of my own hunched figure and barely recognized myself. My face was swollen, my hair disheveled, my clothes rumpled from days of neglect. But it was more than physical appearance—there was something altered in my very posture, as if grief had reshaped me at some structural level.

In that moment of strange clarity, I understood what I had lost with Elena. She had been the only person who had truly seen me, who had recognized my defenses for what they were without condemning me for them. She had challenged my most sweeping dismissals, had insisted on the value of small mercies in a world I saw as irredeemably corrupt. In her presence, I had felt a kind of thawing, a tentative opening toward possibilities I had long since rejected. And though I had never spoken the words, I had loved her with an intensity that surprised me, that contradicted everything I thought I knew about myself.

I should have told her. The thought circled in my mind like a persistent bird. I should have told her on those quiet mornings when sunlight filtered through the curtains, gilding her skin as she slept beside me. I should have told her on the evenings when we sat across from each other at our small kitchen table, debating some point of theory or policy. I should have told her in the hospital, when each day might have been our last. But I had held back, had maintained a reserve that now seemed like the most profound cowardice.

And so I knelt there on the floor of our apartment, surrounded by the artifacts of our shared life, and confronted the full measure of my failure. I had not just lost Elena; I had failed her in the most fundamental way. I had withheld the truth she deserved to hear, had kept it locked away out of some misguided fear or pride. The realization was a physical pain, a tightness in my chest that made it difficult to breathe.

As the night deepened around me, I remained motionless, holding the scarf with its single strand of hair, haunted by all that might have been different if I had found the courage to speak. The silence of the apartment pressed against me, a tangible reminder of all that was lost, all that would never be recovered. And in that silence, I made a kind of promise to Elena—not that I would move on or find peace or any of the platitudes offered to the grieving, but that I would acknowledge, at least to myself, the truth I had never spoken to her: that I had loved her, completely and without reservation, in a way that defied all my cynical predictions about human connection.

It was, perhaps, a small and private reckoning, insignificant against the vast fact of her absence. But in that moment, it felt like the only honest thing left to me—this belated recognition of what she had meant, this silent confession that would never reach her ears.

PART VI

Without Elena’s presence, I found academic life intolerable. Students funneling through the university, mostly fixated on networking and credentials, left me cold. Colleagues advocated for “innovation” in teaching, which boiled down to commodifying everything into cost-effective training modules. My final publication, “The Necropolitics of Institutional Compliance,” hammered the notion that universities reduce knowledge to a saleable commodity, draining genuine inquiry of any transformative power. The administration took offense. Some hinted I should move on. I did. I wrote a terse resignation letter, packed up my handful of possessions in the campus office, and left.

I retreated to a small studio apartment downtown, ironically near the corporate district. The swirling chaos of the city—financial behemoths, garish advertisements—assaulted my senses daily. At times, I wandered the sidewalks in the early morning, surveying bleary-eyed workers on their commutes, scanning each face for a shred of empathy. I seldom found any. It was as if everyone moved through life locked in unseen shackles, hunched under the weight of tasks they had never chosen.

I began drafting a new manuscript, expanding on the core themes of my dissertation but letting my rage soak every line. Societies revolve around fantasies of success, synthetic emotions peddled in glossy packaging. Food is chemically tweaked to manipulate the palate; pills are doled out to stifle real feelings; social media is curated to keep everyone anxious yet captivated. In short, I concluded that modern existence has become an elaborate stage show that no one dares exit, for fear of the unknown outside. My notebooks overflowed with references to historical misanthropes—Schopenhauer, Cioran—who had glimpsed the darkness long before.

Day to day, I saw humanity as a swarm of transaction-seeking insects, each grappling for advantage at the cost of the other. I was not naive: we must, after all, buy groceries, pay rent, keep the lights on. So I complied, albeit with bitter resentment. At the corner store, I avoided pleasantries, handing cash to the cashier with minimal eye contact. I ignored small talk from neighbors. My nights were spent reading subversive texts or analyzing economic data that confirmed the unstoppable march of corporate hegemony.

Occasionally, I glimpsed a mother pulling her child close on the subway, or a street musician playing ragged tunes for spare coins. I recognized faint embers of humanity smoldering in unexpected corners. But each time, my cynicism roared back, reminding me that even these acts became part of the spectacle—mom brandishing maternal affection as a performance, musician exploiting pathos to earn a living. I directed my fury at everything—advertising illusions, clickbait headlines, superficial job fairs—painted in the bright colors of success to keep the masses enthralled. The city did what it could to swallow me in its mirages. I refused to be devoured, though it cost me what remained of my peace.

One afternoon, a glossy envelope slipped under my door—no return address, but the stamp read “Skyline Tower: 39th Floor.” Inside, a neatly printed card:

“Victor Mercer,

You are cordially invited to a promotion celebration for Igor Kuznetsov.

Venue: The Aurora Bar, Midtown.

We would be honored by your presence.”

I stared at the card for a long moment, heart pounding against my ribcage. So Igor had risen far enough to host gatherings in exclusive bars. Or perhaps his new firm sponsored it. I felt a tug of conflicting impulses: The teenage friend in me wanted to see him, to revisit the bond that had once bolstered us both. The embittered critic in me scorned any thought of attending. But in the end, curiosity won out. I had to see what he had become—whether the corporate world had transformed him completely or if traces remained of the boy who once sat with me in that dilapidated library, where we imagined lives defined by more than the factory smoke that choked our horizons.

PART VII

The Aurora Bar was perched atop a sleek high-rise, all polished steel and tinted glass. I arrived that evening, stepping into an elevator occupied by three young executives in tailored suits. They chatted about market share, IPOs, stock options—words that reminded me how far from academia I’d drifted. The elevator hissed to a stop on the 39th floor, opening to a shimmering foyer of subdued lighting and upbeat lounge music.

I moved into the main hall, scanning for any sign of Igor. Dozens of well-dressed individuals sipped cocktails, exchanging pleasantries in voices pitched just loud enough to signal self-importance. A bored DJ spun a low beat, while a waitstaff glided among the guests with polished efficiency. I felt abruptly out of place in my thrift-store blazer, but I refused to show discomfort.

Igor spotted me first. He excused himself from a group, crossing to me with the confident stride of a man certain of his success. In the years since I’d last seen him, he had let his hair grow a bit longer, but his eyes still carried the piercing intensity from our youth.

“Victor Mercer,” he greeted, voice warm enough on the surface. “You haven’t disappeared after all.”

I forced a small nod. “Not yet. Though I imagine you’d prefer it if I had.”

He gave a short laugh, ignoring the jab. “I’m glad you came. It’s been too long. What do you think of this place?” He gestured expansively, as though the dazzling bar and city skyline were personally his to bestow.

I glanced around, noticing the neon reflections dancing along the floor-to-ceiling windows. “Remarkable what budgets can buy,” I said, keeping my tone neutral. “You’ve done well for yourself.”

He shrugged, taking a sip of an amber drink. “When you set aside lofty ideals and engage the real world, you’d be surprised how much you can accomplish. There’s so much potential to be tapped. I always told you that.”

Something in that resonated with the memory of our old debates. “Potential for what? More consumption? More manufactured desires?”

Igor chuckled. “You’re the same, I see: condemnation at every turn.” He waved a hand around the bar. “Let’s not do this here. Later, I’d like a real conversation, for old times’ sake. But first, I have some guests to greet.”

He patted my shoulder, drifting away to another circle of well-dressed sophisticates. I watched him carefully, noticing the effortless way he integrated himself. I remembered how awkward we were in high school, barely able to talk to anyone else about our reading. Now, he seemed molded to this environment, a polished piece of the city’s glossy puzzle.

Left to my own devices, I wandered through clusters of conversation. I overheard monologues about venture capital, investment strategies, expansions into overseas markets. Occasionally, someone tried to strike up small talk with me, only to falter when they discovered I had no position worth networking over. It was a near-caricature of corporate banality, a living example of everything I had dissected in my essays. People clinging to status, seeking validation in ephemeral successes.

As the evening wore on, I seized a moment to step onto the outdoor terrace. The breeze was cool, carrying the hum of traffic far below. I gazed at the radiant city lights, thinking how Elena would have recognized this spectacle as emblematic of capitalism’s hypnotic power—so bright, yet so empty. I closed my eyes, letting the memory of her voice steady me.

When I returned inside, much of the crowd had thinned, heading off to after-parties or early meetings. I finally managed to corner Igor near the bar, where he poured himself another drink. He looked tired but proud, the faint smirk of achievement etched onto his face.

“Victor,” he said, leaning in. “I hear you’ve locked yourself away downtown, living off your meager savings, writing more scornful essays. Information travels in certain circles.”

“And you keep your ear to the ground, apparently,” I replied, stiffening. “So how’s that working out, being the city’s new star of data manipulation?”

His smile tightened. “You say manipulation, I say focusing behavioral patterns where they naturally want to go. People hunger for guidance. If you direct them properly, they’re happier for it. We provide that service.”

My stomach churned. “Service? Steering entire populations toward half-baked phantoms of desire and self-improvement, so they’ll buy more, watch more, chase more. That’s not service. It’s exploitation.”

Igor set down his glass, eyeing me with an unsettling calm. “Condemn or condone—those are just moralistic categories. In reality, everything is reciprocal. The city demands engineered perceptions. We deliver them. Society thrives on them, Victor. When did you start believing in untainted truths?”

I ground my teeth. “Where does that leave accountability? Don’t you feel any twinge of guilt turning people into data sets?”

He sighed as though talking to a slow student. “People are resources. They can be used responsibly or irresponsibly. I’m choosing the more directed approach, which is more than some can say.”

I remembered how, as teenagers, we sat around homemade charts, believing we’d never let greed define us. “This is ‘responsible’ to you? Building an empire on a prison of perception where the inmates believe they chose their own cells? God, Igor, who are you?”

He shrugged. “I adapted. You refused. That’s the difference.”

A short silence stretched between us, bristling with old anger. Then someone from the board called Igor over. “I’ll be back,” he murmured, leaving me with an exasperated wave of the hand.

Resigned, I circled the room, engrossed in my own frustration. By the time the crowd dwindled with the last notes of lounge music, Igor reappeared near a table of empty glasses. His posture spoke of subtle victory, the conquering man surveying his domain.

“Victor,” he said, rolling my name on his tongue. “We should talk properly now, away from all these formalities.”

“Talk, then,” I muttered, crossing my arms. “I’m all ears.”

He glanced around, ensuring no eavesdroppers hovered. “I’ve followed your recent work—insofar as it’s circulated online. You keep rehashing that humanity is corralled by corporate interests, that capitalism chews up human potential. But you still shop in the same stores, use the same utilities, breathe the same polluted air. Don’t you see the contradiction?”

I swallowed a surge of anger. “Surviving in a corrupt system doesn’t mean I endorse it. We can’t simply step outside of society. We exist in the crucible, whether we like it or not.”

Igor took a slow sip, then set his glass aside. “So it’s survival for you, and condemnation for everyone else. Meanwhile, I built something. I formed a firm that models human behavior, not to crush people but to guide them. You call it horrifying, but you have no alternative except moral grandstanding.”

I felt the blood pounding in my temples. “Is that what you call it? Moral grandstanding? Perhaps it’s just the last shred of honesty in a world that wants to be fed apparitions about progress.”

He leaned closer, voice sharpened by the tension between us. “You don’t get it. Morality is the same as everything else—moldable, a means to an end. If you’re too weak to compete, you cloak your failure in moral outrage.”

A deeper pain flared in me. He was no longer just my old friend with a different viewpoint. He was a man whose ideology stood as the polar opposite of everything Elena and I believed. “You’re insulting the only real friendship either of us had,” I whispered, remembering the nights in that old library corner. “You sound like the very men we once despised—those who leveraged power for self-gain, ignoring the cost.”

Igor’s gaze flickered with something close to regret. He inhaled, then responded in a calmer tone, “We were children then, clinging to naive illusions of our own moral greatness. But the real world is not your dissertation, and it’s not Elena’s heartbreak. It’s a battlefield. Overcome or die.”

The mention of Elena cut me like a fresh wound. My fists clenched at my sides, nails biting my palms. “You have no right to speak her name,” I hissed.

He studied me, clearing his throat. “I know she found capitalism monstrous. She called it a viral system. She believed it would devour everything. But she missed how quickly that virus adapts—and how unstoppable it is once you realize it can’t be tamed or killed, only navigated.”

Hearing Elena’s words quoted like that triggered a near-blinding rage. For a moment, I envisioned punching him, letting years of frustration spill out. But my anger mingled with sorrow, tangling me in place. My voice trembled. “Don’t you dare tarnish her memory by justifying your predatory ambitions. She believed in compassion, even after all she saw. You twist it into another commodity.”

Igor drew back, eyes steady. “You can keep worshipping her memory. But I suspect even she would see that clinging to purity is self-defeat. At least I’m trying to shape the world into something. You’re merely railing at it from a corner.”

I pressed a hand to my forehead, trying to quell the dizzy swirl of despair and resentment. Could this truly be my old friend, the boy who once strove for knowledge alongside me? Now I saw a man enthralled by power, indifferent to the moral quicksand he sank into. Finally, I couldn’t bear his presence any longer. I turned on my heel, ignoring his attempt to speak again. I left the Aurora Bar with a sense of something irreparable in me having finally broken.

PART VIII

Numbness settled over me in the days that followed, a bleak confirmation that my worst suspicions about humanity had an intimate embodiment in Igor. We had once braved the stagnant gloom of our hometown, forging a loyal companionship out of battered textbooks and idle afternoon debates. Now, we stood at opposite extremes of the moral spectrum, each outraged by the other’s convictions.

I tried to pour my new wave of anguish into writing. Page after page dissected how corporate culture wasn’t just an economic system but a devouring force, absorbing every human impulse until nothing authentic remained. I argued that the city, the entire modern world, survived by flooding people with illusions—synthetic emotions, curated fantasies, the promise of self-fulfillment if only they would relinquish any lingering doubt. I infused my text with the scorn of a man who had witnessed the final betrayal from his closest friend.

Yet the act felt hollow. Elena’s memory haunted every sentence. She had once said that a shred of compassion might survive the scorched landscape of capitalism. Without her, I had no reason to preserve such optimism. Igor’s triumphant success iced any hope I had for a moral revolution.

I have withdrawn now, not from any personal failing but because it is the only logical response to a civilization that exists as an elaborate theater of false consciousness, where the audience applauds their own captivity. If my disdain has evolved beyond personal sentiment into philosophical position, it is because corporate mechanisms have methodically exploited every fault line in human consciousness. Advertising doesn’t merely manipulate insecurities but manufactures them, creating deficiencies where none existed to sell their predetermined solutions. Politicians construct elaborate facades of representation while serving as brokers in the marketplace of power. The populace, reduced to nodes in a vast network of consumption, clutches at synthetic narratives that provide the illusion of meaning within their diminished horizons. Igor, ironically, stands at the apex of that synergy, forging data analytics into an unstoppable push for commercial and ideological control.

I no longer speak to past colleagues. If I need supplies, I buy them online, avoiding the vacant stares of overworked store clerks. The city appears to me as a carnival of cruel distractions, a labyrinth of bright hues that obscure hollow hearts. Everything has become transactional, from the way neighbors greet each other to the way lovers cling, hoping to stand out from the constant churn.

In the quiet of my unlit studio, I reread old passages from my dissertation, the lines where I once tried to capture the essence of consumer captivity. It pales in comparison to the reality outside my window. Truth, it seems, can be more savage than any theory. Elena’s gentler arguments occasionally surface in my thoughts, but I have no capacity to carry her half-hope. I’ve lost it with her passing.

I record these experiences as a final testament to how easily one can drift from earnest questing to absolute misanthropy. If I have asked more of humanity, it’s because I once believed in certain possibilities—for moral fortitude, for empathy in the face of exploitation. Yet the more I probed, the more I realized how thoroughly the corporate machine has infiltrated every moral vantage, twisting discontent into profitable niches, swallowing rebellion, exalting cynicism as long as it can be monetized.

Igor and I began side by side, both seeking escape from that grim factory town where our fathers barely clung to meager livelihoods. We found comfort in each other’s intellect, forging a bond that seemed indestructible. But in the end, that very bond burned under the friction of adult ambitions. My insistence on seeing the skeleton beneath society’s skin rendered me unfit for its embrace. His talent for adorning that skeleton with seductive flesh made him its celebrated architect. Somewhere in the gulf between those positions, all the love, hope, and camaraderie of our youth vanished.

I cannot conjure false comforts to shelter my wounded spirit now. I know what Igor would pronounce from his gilded tower: that I sacrifice everything for the cold solace of moral conviction. Let him speak these hollow words. I have no desire to convert him, nor to rescue anyone from the labyrinth of corporate sedation. My manuscripts remain half-finished, a flurry of pages that few will read, fewer will accept. Sometimes I consider releasing them online under a pseudonym, but what difference would it make? The city continues its relentless march, adorning itself with each new brand, each product cycle, each campaign that gathers the masses like livestock beneath the slaughterhouse sky.

And so I close this testament with the clear-eyed wisdom that comes from witnessing the full measure of our collective descent. I am, at last, done. Done with the myth of progress that veils our regression. Done with awaiting institutions to redeem themselves—let them find their own salvation if they can, before the tide returns to claim what hubris built. Done with placing faith in humanity’s moral compass when it has led us only deeper into darkness. My love for Elena—fierce, unspoken, and luminous—revealed to me that sparks of authentic decency once flickered in the human heart. But in her absence, I see no reason to remain a participant in this grand, decaying theater. Let them face their terrible fates. Let empires crumble under the weight of their own corruption. I withdraw not in defeat but in recognition of a fundamental truth: some battles cannot be won because the battlefield itself is poisoned.

Thus, let these pages stand not as a confession, but as a diagnosis. I have examined the social body, probed its organs, and found them malignant. I have watched the last person I truly could love slip away into the oblivion of disease, and I have seen my only friend discard any pretense of solidarity to champion the new frontier of mass manipulation. My mind is clear, my heart is calloused, and my verdict is final:

Humanity does not deserve witnesses. It deserves only the silence of its own making.

I withdraw, utterly, in recognition that this is the only rational response to a civilization orchestrated by predatory appetites and choreographed delusions.

—Victor Mercer

Yikes! “Decay” was extremely well-written, as if by a PhD as the narrator in fact was. The text is immaculate, the metaphors copious and well done. However, there is no denouement, no resolution. The MC begins and ends as an outraged critic of society and in the end, what happens? Does he commit suicide? Does he enroll in an MFA program? Does he live on an isolated island for the remainder of his days? We aren’t told. He merely becomes even more firmly locked in his perception that the rest of the world is at fault. This was such an intelligently written story, but I emerge unsatisfied with the ending.