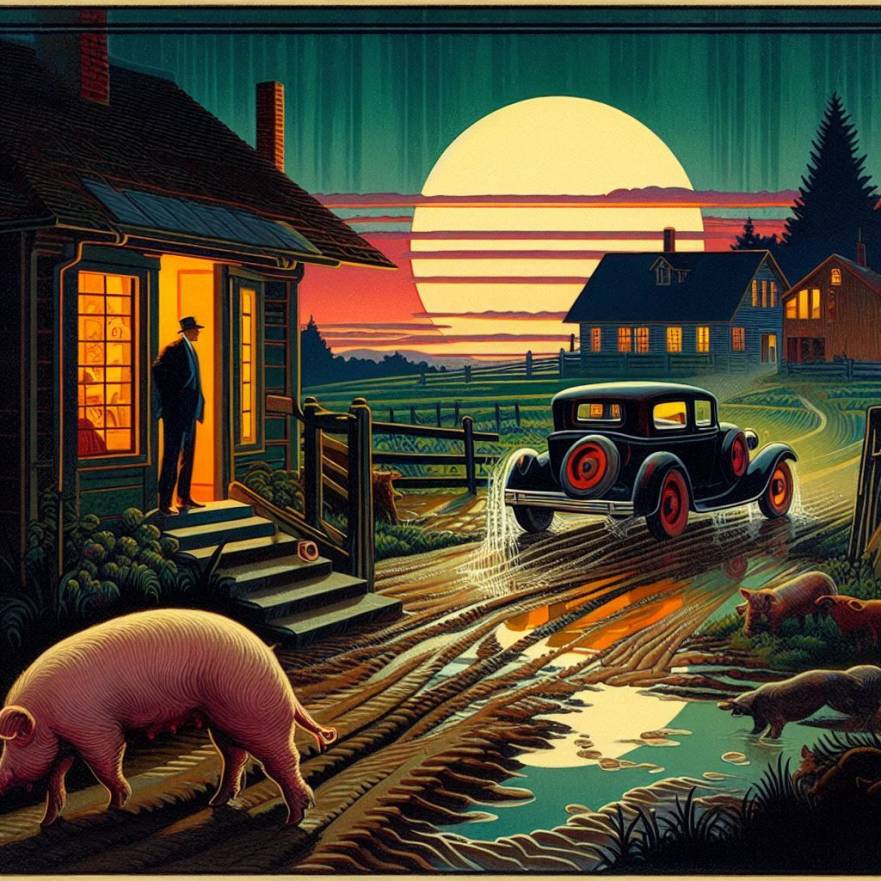

Suppertime by Mark Manifesto

Suppertime by Mark Manifesto

If names bring the unspoken to life, the doctor had given Arthur arthritis. No matter how often he sealed the walls, dust always found a way in to blanket the family room and its tacky ranch decor— ornamental lassos, spurs, bullhorns, and American flags. His question still stood. “Why decorate a ranch in the theme of ‘ranch’, Marge?” Then again, it’d grown on him since she passed.

Breakfast as usual. Two fried eggs over easy with white toast. The coffee machine spurted, the bourbon glugged, and indigestion burned the lining of his esophagus. With a firm grasp on his boiling stomach, he looked to the painful light of dawn. A long time until supper. What’s the opposite of ‘seize the day’? He thought of the work ahead and pulled at the remaining webs of hair on the sides of his head. Can’t I just sit for once and enjoy a cold beer without any of this bullshit? This God-forsaken patch of decayed earth. One day without smelling of shit. Getting weak in old age. Work is what man was for. And fertilizer.

Bang!

A crash from the front porch. His throat swelled shut. Was it them? No, it couldn’t be, never this early. Still, he looked with breathless hope. Just the welcome sign on the door.

Before the day swallowed him, Arthur stood in observance of the memorial cards on the refrigerator. Marge’s and their youngest, Benny’s. Held in forever in two dimensions with matching hazel eyes and golden hair. His caress bore an unholy reverence and sensual ache he knew wasn’t healthy, but he’d earned it. Arthur took Marge’s pearl necklace from his pocket and looked over the opaline piece. He heard her voice, “You never know who’s watching.” A sharp sting forced his eyes closed. They still smelt like her, at least he thought they did.

With the first step onto the front porch, the El Paso heat crashed. A long way from Eden. Maybe not that far. Maybe these ghosts were angels. He pulled his frayed Astros’s cap down and trudged into the blue world. Across the gravel driveway towards the barn, the cows and cocks sang. The paint-chipped doors were getting heavier everyday. Sweat beaded on his back and the musty smell of hay, dust, and shit— his own perfume— lined his nostrils. Beyond the metal pens and the hungry mooings, he opened the pasture access and cursed at the sudden cloud of dust in his eyes. The flatulent animals wasted no time falling into the day long task of grazing. There was something laudable in their mindless idling, still, they left a sour taste in his mouth. He hacked up some mucus and swallowed it down.

A cold gust swept from behind. Pin-prick goosebumps down his arms. Someone was watching… he smiled. Arthur scanned the barn, praying—

“Marge?” he asked, reverently inspecting the bales of hay.

Maybe Benny. This is where it happened. He peered into the empty horse pens and swallowed his apprehension. “You there?” he asked. Just dirt and tools he hadn’t touched in years. He rubbed the sting from his eyes and pondered how the only thing worse than being alone, was having hope.

Weary in the growing heat, he watched the cows split over the hills and thought about the hassle of wrangling them. With Marge, even for two old souls, it had all been doable. But now he was working himself into a coffin. Maybe today. A part of him wished he still had horses to help, but that wasn’t an option— both from age and conviction. He failed to keep his mind from the echoed crack of hoof against preadolescent skull. The image of brain and blood— Benny’s as Marge ran him to the truck— and the horse’s after Arthur grabbed the shotgun. Red hay and clumps of shit.

The chickens ran wild within the coop as he spread the feed, and with them distracted, he checked for eggs. Eight. Less every day. And for reasons beyond him, they weren’t reproducing. Too distracted maybe. Lost in their own world. Maybe just old. He took them in a towel, started through the barn, and froze. The bundle dropped. Broken yolks stained the loose hay. There in the center of the space, Marge. Unmoving in a tattered white nightgown, so beautiful it hurt. Witless and lost, staring through gorey black eye sockets. Dark veiny circles pillowed under the cavities. Her skin, a ghoulish pale-green, refused the light. But it was her. She’d come back, just as she’d done the day before, and the day before.

He rushed as fast as his joints would permit and took her hands. Soft like understuffed pillows and dry. But hers.

“Marge,” he said, words weak on quivering, sun-cracked lips.

She continued to stare into space, lips parted slightly to show decaying teeth. He stroked her dry, wrinkled cheek and kissed her pallid knuckles.

“I had a dream about you last night. We were riding pale horses through the desert. You said you’d found something I needed. Can you tell me what?” Arthur whispered, gently embracing her skeletal frame. “Is Benny coming? What about my dad?”

She bore a harsh, earthy smell that he was coming around to.

“I brought you something,” Arthur said, fishing the pearls out. “You’re favorite.”

She didn’t react.

“That’s alright hun’. I’ll put them on for you.”

Arthur’s quivering, work-mangled fingers struggled with the small latch before he draped them softly around her neck.

“Just like how it used to be,” he said. With a painful smile, he nestled his face into her wiry hair. Nothing wrong with silence.

“Arthur?” a gruff voice carried from the barn’s entrance.

Arthur looked up. Arms around nothing. A light crash. The pearls cracked and scattered. His throat locked up and he dropped to his knees, fumbling with the disbanded pieces.

Hal entered charily and slicked his curled mane under his full-brimmed hat. Arthur growled. He was a good man with a good family, a decent rancher, and a nosey bastard of a neighbor.

“Didn’t mean to bother you, Arthur,” Hal said, stopping after a few steps and airing out his flannel.

Shit! Arthur dove at a lone pearl rolling towards the drain.

“You need some help?” Hal asked, inspecting his task curiously.

“Get the hell back!”

Hal’s brow raised in alarm. He had half a mind to throw the cracked beads and curse him into his truck. There was a whip on the tool wall. A machete. With a clenched jaw and a handful of disappointment, Arthur asked, “What do you want, Hal?”

“I just wanted to come by and check on you. No one’s seen you since… well last month.”

“A lot of work running a ranch alone.”

“I hear you,” Hal said, inspecting the barn. “You know, if you ever need help, just let me know. I’m happy to come by or send the boys.”

Sharp cardiac pain stole his breath. He looked around, hoping Marge would be in one of the corners. Fuck you, Hal.

“Mighty kind of you, but I’m managing,” Arthur said, the words solidifying his conviction. He started off towards his workbench hoping curtness might end the conversation.

“I wish my kids had your drive. Maybe one of these days you could teach em’ a lesson.”

Given how Connie and John— wherever they were— turned out, his parental averages weren’t great. If only it could’ve been one of them, he thought. He nodded and ground the tip of his fixed-blade into the time-worn cavity on the workbench

“You know Arthur, we’re all a bit worried,” Hal said, kicking a hard clump of dirt.

“Who’s we,” Arthur growled, pointlessly inspecting a few tools on the wall that would by no means aid the repair of Marge’s pearls.

“Everyone, Dave, George, Doc Randle, my wife… me. It’s not good to be alone too long.”

“I’m managing.”

“You’re a tough son’ bitch, but everyone needs a bit of company.”

“I got plenty…”

Hal looked around the empty barn. “Not counting livestock.” Arthur caught his smile before it turned cruel. “What say you come on over for supper tonight,” Hal continued.

And forgo sacred time? It took a lot not to crack him with the hammer. “I’ve got company tonight.”

“You do?” Hal asked, incredulously.

“Yes.”

“How bout’ we plan for another day then. The ole’ lady would love to have you.”

“Love to be had,” Arthur said. Now get the fuck out. The weight of Hal’s stare dug into Arthur’s back but he refused to acknowledge it.

“Just take care of yourself Arthur. Don’t wanna see you going off the edge.”

“If I find myself headin’ that way, I’ll let you know.”

Consternation turned Hal’s expression somber. “Please do,” he said, extending his hand. Arthur gave it a reluctant shake.

With a worried grin, Hal nodded and kicked back to his blue pick-up truck. Arthur watched him flip the U-turn down the driveway and off on the main road. When he was sure Hal was gone, he ran.

“Marge!” Arthur called, hurrying around the barn. “Marge! Dammit!”

Pain shot through his foot as it cracked a support beam. An eerie groan rang from the loft above. He froze and watched the shoddy wood in horror. His lungs filled again and he figured, not my time yet.

10:05 AM. Nine more hours.

Work cures all. Wall repairs, rat traps, and the decapitating of a feisty rattler with a hand shovel. A few more and he could make a nice belt. A new man. Head light with loose leaf chew and Lone Star, he leaned on the railing of the pig enclosure and watched them squeal and rustle through the muck. Ignorant bliss. If only they knew what was waiting in December. He grinned. Joyful and witless, the swine rushed the trough and the freshly poured slop, squawking as they wrestled for position.

He pulled up a wooden crate into the shade, packed another glob of tar in his lip, and watched the feast. How and why Benny had been so fond of these creatures, he didn’t know. How can you be fond of something that plays in shit? Then again, they didn’t have much choice. He was a strange and beautiful boy, Arthur’s own Huck Finn. Where John or Connie had spent most of their time stealing his moonshine or downtown with cash taken from his wallet, all Benny wanted was to be out here. Brushing cows, feeding horses, kissing pigs— one whiff and you’d know. Arthur rubbed the crust from his eyes and watched Oscar shoulder two sows for room. If only Benny could see how big his hog had gotten. Marge called from somewhere in the past, “Twins if you don’t count the tail.” He still couldn’t believe he’d been convinced to bring the thing in the house for Benny’s first communion dinner. Arthur wouldn’t let himself smile. A man can’t get attached to animals. A useful stud, but there were no Wilburs around here. Just some pigs. Hell, they wouldn’t have names if it wasn’t for the kids.

Still, there was no denying the beast’s swagger. Moved damn well for an old timer. But… what’s that? A slight undulation within the mud. Up and down. Like a balloon filling and deflating. He spat a glob of tar and moved closer, curiosity and fear rippling under the skin. Was it him or this space that was causing this misreality?

Within the pen, he sloshed past the sunbathing hogs before the strange spot of mud. From over top he watched the rising and falling and wondered, Someone new? His mouth went dry. He pressed his hand to the muck. Something was breathing under there. Handful after handful of filth until his hand came upon cloth, no a shirt. A chest. A body. The realization crashed like lightning, the manure’s texture— soft, coagulant, and moist— was almost exactly like the tropical Vietnam soil which had nearly taken his right leg.

“Are you okay down there!” he said, scraping layers in a breathtaking frenzy until…

He fell back, choking in horror. A man in blood and shit-stained military greens. Private, First Class. Dog-tags which read, ‘Marshall, Stephen C.’ He grabbed at the sharp pain in his chest. His promise rang from hell, “I’m getting you out of here, Marsh!” Friendly fire from overhead, bombs bursting across the ravine, men screaming for retreat, the smell of blackpowder in rain, Private Marshall half-buried, stomach torn open from a rusty dagger— as it still was. Arthur’s hands shivered once again. What could he have done? It was a promise made to comfort. He couldn’t have actually gotten the kid out. He had jungle rot for God’s sakes. The skin and muscle was practically melting. He hadn’t eaten in three days. Weak and scared. He had a wife to get back to and a baby on the way. Orders were to retreat. It’s not like he was going to survive either way? So what if the blade had been meant for him? Marshall made his decision to intervene.

Tears stung as Arthur continued to rake. The boy’s face met sunlight, pale-green with streaks of mud, his expression blank— eye sockets hollowed and outlined with dark veins. If he could just get him out this time. The mud was unyielding and greedy. Arthur wrapped his weak arms around Marsh and heaved until bolts of pain struck in his lower back. He grabbed his shit-slicked hands and pulled—

From behind, a metallic creaking. The pen door— still unlatched— swung open. Standing in the opening, Oscar.

“Shit!” Arthur said, tripping to his feet. Oscar looked over his shoulder, and likely thinking it a game, ran. “Oscar!”

With arduous steps through the muck, his heart thundered. “Get the fuck back!” he said. The sow squealed sharply to boot in its side— perhaps too hard.

He hurriedly latched the pen and turned to a scampering Oscar. The chase was on. His lungs burned but there was no defeat. Left and right. Each time he came close, Oscar turned and dashed just beyond reach. Around the side of the barn, the driveway, and house until his heart pounded at a dangerous pace and his lungs felt they might explode. His legs throbbed with lactic acid. I can’t, he thought.

After rounding the house a second time, he keeled over, hands on his knees, dripping sweat, and wheezing. A thick black loogie caught and hung on his lower lip. The pink bastard wandered in victorious leisure, rooting up small weeds from under the gravel. Alright, Oscar. Alright.

With one last showing of strength, Arthur dashed. In his stride, the world slowed. He felt the lost power of youth. Miles’ worth of endurance. The strength to overpower a steer. The will to beat back the Vietcong. All in there. Oscar’s eyes widened. With a powerful step and spread arms, Arthur flew. Short wispy hairs, smooth flesh. You’re mine. Oscar scampered forward, and the ground was waiting. Gravel dug into his paper skin, pain fired through his chest and ribs, and his head snapped. Oscar looked back, squealed, and ran.

Rolling atop the sharp rocks, Arthur cursed the world and held his ribs. Something was broken. He arched his head back and watched the inverted little bastard run down the driveway, across the main road, and out of sight within the tall grass of the opposite fields.

A primal scream from the darkest part of him echoed across the valley. A lifetime of absolute dominion over the creatures… things had changed. Sheets of dust whipped his face. The blistering sun watched overhead, blindingly white. Blood in his ears throbbed in time with the pain from his chest and legs. Don’t you dare cry, he told himself. These things happen. Now stop pussyfooting and get up. You can’t be late.

2:27 PM.

Eventually, he found the strength to push past his pain and rise. No sign of the little bastard. Somewhere out there living its fat, little piggy life. He kicked a patch of gravel and keeled to the pain in his ribs.

Within the hogs’ pen, he stared at the empty cavity of manure. Shame sealed his lips. They were even. Arthur spat and stumbled bitterly back to the house. He sat at the kitchen table and looked at Benny’s old spot. Whatever happens to that hog is on him, Kid. Dehydration, starvation, torn limb from limb by coyotes or cougars, all justified.

“… Shit”

At the landline’s dial tone Arthur massaged his throbbing temples.

“Hello?” Hal asked, in an amiable tone that made Arthur consider hanging up.

“Hal?” Arthur groaned.

“Hey Arthur… Is everything alright? You sound like you’re in pain.”

“Don’t worry about that none, look, I need a bit of help.”

You fucking pig!

“What with?”

“One of the hogs is out. I tried chasing him down and took a little fall.”

“Shit! I’ll be right over to drive you down to the hospital.”

“No!” Arthur shouted, with Revelation’s fury. With a deep calming breath, he continued, “No. I just need help tracking him down.”

“Of course, I’ll grab the boys. Where’d he go?”

“Out in the hills across the road.”

“Nough said. Anything else?”

Arthur gave his ribs a slight touch, and an immediate wave of pain flooded his body. Damn. “The cows are still grazing, if you could help get them in, I’d be thankful.”

“Consider it done.”

Arthur shook his head, jaws tense as corded steel. More and more of the world slipping away. “Thanks.”

“Don’t mention it.”

A slight crack rang from the plastic of the receiver in slamming it. Indignant curses streamed as Arthur grabbed the beers out the fridge and resigned to the rocking chair on the porch. With a groan and a sigh he took his hat off and closed his eyes to the blanketed heat. Tsh hissed the can. He took a sip, put in a new lipful, and rocked the sun away. A failing body. Ungrateful livestock. Resurfacing memories. If only they could stay longer, he might find peace. Understand why they’d returned. He finished the first can and swallowed the fact that there are no words to aptly describe the terrible prison of time.

What if I could start again, he wondered.

And betray them?

Eventually, a low rumbling carried from the road. The old blue pick-up truck crunched to a stop. Arthur met the gazes of the two boys in the front seat and growled. The bed was empty. Hal approached with a discouraged air, took his hat off and scratched his greasy hair. It would have been better if he said nothing.

“Hey…” Hal said, letting out a long sigh.

“Thanks for trying,” Arthur said, spitting onto the porch.

Hal wanted to explain the failure, but he thankfully moved on. “Maybe we can look again tomorrow.”

Arthur cracked a new can and held back a tirade on Hal’s lackluster generation. Losing a pig was frustrating, but something about Oscar dying out there— suffering as much as Arthur— brought him some pleasure, then equal parts regret.

“I figured it best to grab the cattle before nightfall,” Hal said.

Arthur pointed to the gate running beyond the barn, “You can pull your truck through there. Best bet’s that they’re down by the pond.”

“Shouldn’t take long,” Hal said. He looked to the car. “Boys, get out here! Where’s your manners?”

The two jumped out— Sam and Porter. One golden haired, one black, both nervously avoiding Arthur’s gaze.

“Evening, Mr. Stack,” they said in unison.

Arthur nodded. The kids were frightened of him. Most were. After a moment of wind of crickets, Hal said, “Alright, let’s go.” Gladly.“We’ll be back soon,” Hal said.

The old four-runner disappeared over the dimming hills, a black beetle in the falling sun. Regrets make a man bitter, bitterness fuels regrets. The chair rocked back and forth, always the same track, but comfortable.

The last wisps of daylight sank and a set of headlights came meandering down the hill behind a small herd of jangling and mooing cattle. Barn locked once again for another night and another day, Hal stopped at the porch.

“Sure you don’t wanna get checked out,” Hal asked. “I don’t mean to pry, but—”

“Thanks for everything.”

Hal nodded. “Anything for a friend… I took the chickens in too. Figured I’d just get it done.”

Guilt forced Arthur’s gaze into the dirt. “Thanks.”

“Don’t mention it. I’ll get back out there in the morning and try again.”

“Don’t bother,” Arthur said, crushing the Lone Star beneath his boot. “Bastard’s gone.”

Hal nodded, “Sorry.”

“… There’s worse things.”

“All about perspective, right?” he said, straightening his hat. “I thought you said you was havin’ company?”

Arthur looked down to his watch with a queer smile, rose past the pain, and extended his hand. “They’ll be here.”

Hal took it and said, “Take care, Arthur.”

He watched anxiously as the red tail lights pulled down the road and out of his life.

The kitchen’s bulbs flickered overhead. Quick as his mangled and boney fingers could, he peeled, cleaned, and roasted, every few minutes peering around the corner to the table. When the potatoes were good and boiled, the peas plump, the corn steaming, and chicken golden brown, he went to the cabinet and grabbed four, no six plates along with silverware and napkins. Best to be prepared.

He set the table, pulled the chairs, and returned to the kitchen. An eerie creak came from the living room. Arthur stared frozen into the blackness beyond the window, afraid to turn, afraid of disappointment. A chill ran from his back to his fingers, and he smiled.

Serving plates in hand, he brought them to the table and the four inert and rigid guests. At the far end sat Marge in her tattered nightgown, on the left side, Benny in his blue overalls, his blonde bowl cut dry, beautiful, and stained red by split his skull, opposite him was Arthur’s mother in the blue dress from his baptism and wedding alike, and at her side, a blood-crusted Vietnamese boy with a shallow 5.56mm entry wound in the forehead, and mushroomed exit out the back. Eight hollow eye sockets, four frozen hearts, and a deeply grateful man.

Ring! Ring!

Arthur jumped to the kitchen landline, afraid the noise might scare them off.

“What!” he shouted.

“Arthur,” Hal said. “We found your little guy over here by the house.”

Arthur froze and looked back at Benny.

“He’s a good ole’ hog. Really likes the kids,” Hal laughed. “I’m surprised he ran off. He just plopped down over here, no need to pen him or anything. I can bring him over—”

“No!”

Silence.

“No?”

“No! Not right now,” Arthur said, panting.

“It won’t take more than a few minutes—”

From the interruptions, to injury, to his failings as a man; all he wanted was supper. In a voice endowed with hate, Arthur said, “Hal, if I hear that truck of yours coming up my driveway tonight, I’m grabbing my shotgun…”

“What? Are you serious?”

“Don’t test me!”

Shame yielded a sheen of tears, but wrath was his comfort.

Hal snarled, “What the hell is wrong with you you old son of a bitch—”

Arthur hung up before he could finish. His heart hammered painfully and forced him to brace against the wall to catch his breath. Guilt swelled, but he tried to ignore it. At least for a few hours. Relief came in the face of four pale-green faces. “Sorry ‘bout that.” He made his way around the table and kissed each of them. Cold, lifeless flesh which tasted of blood and earth.

A part of Arthur knew what the nightly ritual was doing to him. But sometimes you can’t let go. He sat and admired the past, each motionless and unaware of one another or Arthur; but they weren’t as dead as they seemed. Each breath he drew was proof of that. He smiled and picked up his fork.

* * * * THE END * * * *

Copyright Mark Manifesto 2024

A really creepy story, explaining what profound guilt and loneliness can bring out in a man. Rich language, grand metaphors and excellent, compelling backstory. I thought this was a wonderful story. Thanks so much for sharing.